Special thanks to Andrew Miller for coming up with this attack, and to Zack Hess, Vlad Zamfir and Paul Sztorc for discussion and responses

One of the more interesting surprises in cryptoeconomics in recent weeks came from an attack on SchellingCoin conceived by Andrew Miller earlier this month. Although it has always been understood that SchellingCoin, and similar systems (including the more advanced Truthcoin consensus), rely on what is so far a new and untested cryptoeconomic security assumption – that one can safely rely on people acting honestly in a simultaneous consensus game just because they believe that everyone else will – the problems that have been raised so far have to do with relatively marginal issues like an attacker’s ability to exert small but increasing amounts of influence on the output over time by applying continued pressure. This attack, on the other hand, shows a much more fundamental problem.

The scenario is described as follows. Suppose that there exists a simple Schelling game where users vote on whether or not some particular fact is true (1) or false (0); say in our example that it’s actually false. Each user can either vote 1 or 0. If a user votes the same as the majority, they get a reward of P; otherwise they get 0. Thus, the payoff matrix looks as follows:

| You vote 0 | You vote 1 | |

| Others vote 0 | P | 0 |

| Others vote 1 | 0 | P |

The theory is that if everyone expects everyone else to vote truthfully, then their incentive is to also vote truthfully in order to comply with the majority, and that’s the reason why one can expect others to vote truthfully in the first place; a self-reinforcing Nash equilibrium.

Now, the attack. Suppose that the attacker credibly commits (eg. via an Ethereum contract, by simply putting one’s reputation at stake, or by leveraging the reputation of a trusted escrow provider) to pay out X to voters who voted 1 after the game is over, where X = P + ε if the majority votes 0, and X = 0 if the majority votes 1. Now, the payoff matrix looks like this:

| You vote 0 | You vote 1 | |

| Others vote 0 | P | P + ε |

| Others vote 1 | 0 | P |

Thus, it’s a dominant strategy for anyone to vote 1 no matter what you think the majority will do. Hence, assuming the system is not dominated by altruists, the majority will vote 1, and so the attacker will not need to pay anything at all. The attack has successfully managed to take over the mechanism at zero cost. Note that this differs from Nicholas Houy’s argument about zero-cost 51% attacks on proof of stake (an argument technically extensible to ASIC-based proof of work) in that here no epistemic takeover is required; even if everyone remains dead set in a conviction that the attacker is going to fail, their incentive is still to vote to support the attacker, because the attacker takes on the failure risk themselves.

Salvaging Schelling Schemes

There are a few avenues that one can take to try to salvage the Schelling mechanism. One approach is that instead of round N of the Schelling consensus itself deciding who gets rewarded based on the “majority is right” principle, we use round N + 1 to determine who should be rewarded during round N, with the default equilibrium being that only people who voted correctly during round N (both on the actual fact in question and on who should be rewarded in round N – 1) should be rewarded. Theoretically, this requires an attacker wishing to perform a cost-free attack to corrupt not just one round, but also all future rounds, making the required capital deposit that the attacker must make unbounded.

However, this approach has two flaws. First, the mechanism is fragile: if the attacker manages to corrupt some round in the far future by actually paying up P + ε to everyone, regardless of who wins, then the expectation of that corrupted round causes an incentive to cooperate with the attacker to back-propagate to all previous rounds. Hence, corrupting one round is costly, but corrupting thousands of rounds is not much more costly.

Second, because of discounting, the required deposit to overcome the scheme does not need to be infinite; it just needs to be very very large (ie. inversely proportional to the prevailing interest rate). But if all we want is to make the minimum required bribe larger, then there exists a much simpler and better strategy for doing so, pioneered by Paul Storcz: require participants to put down a large deposit, and build in a mechanism by which the more contention there is, the more funds are at stake. At the limit, where slightly over 50% of votes are in favor of one outcome and 50% in favor of the other, the entire deposit it taken away from minority voters. This ensures that the attack still works, but the bribe must now be greater than the deposit (roughly equal to the payout divided by the discounting rate, giving us equal performance to the infinite-round game) rather than just the payout for each round. Hence, in order to overcome such a mechanism, one would need to be able to prove that one is capable of pulling off a 51% attack, and perhaps we may simply be comfortable with assuming that attackers of that size do not exist.

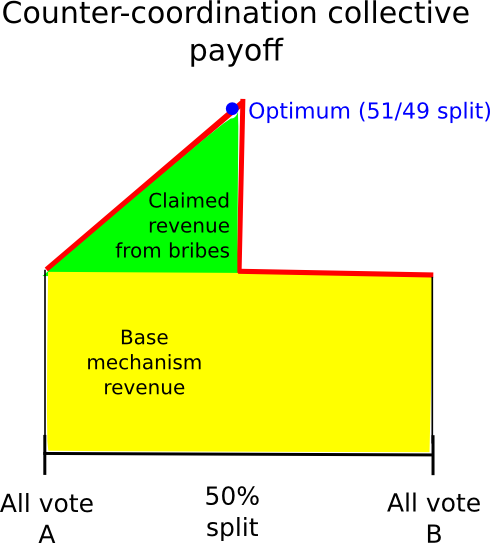

Another approach is to rely on counter-coordination; essentially, somehow coordinate, perhaps via credible commitments, on voting A (if A is the truth) with probability 0.6 and B with probability 0.4, the theory being that this will allow users to (probabilistically) claim the mechanism’s reward and a portion of the attacker’s bribe at the same time. This (seems to) work particularly well in games where instead of paying out a constant reward to each majority-compliant voter, the game is structured to have a constant total payoff, adjusting individual payoffs to accomplish this goal is needed. In such situations, from a collective-rationality standpoint it is indeed the case that the group earns a highest profit by having 49% of its members vote B to claim the attacker’s reward and 51% vote A to make sure the attacker’s reward is paid out.

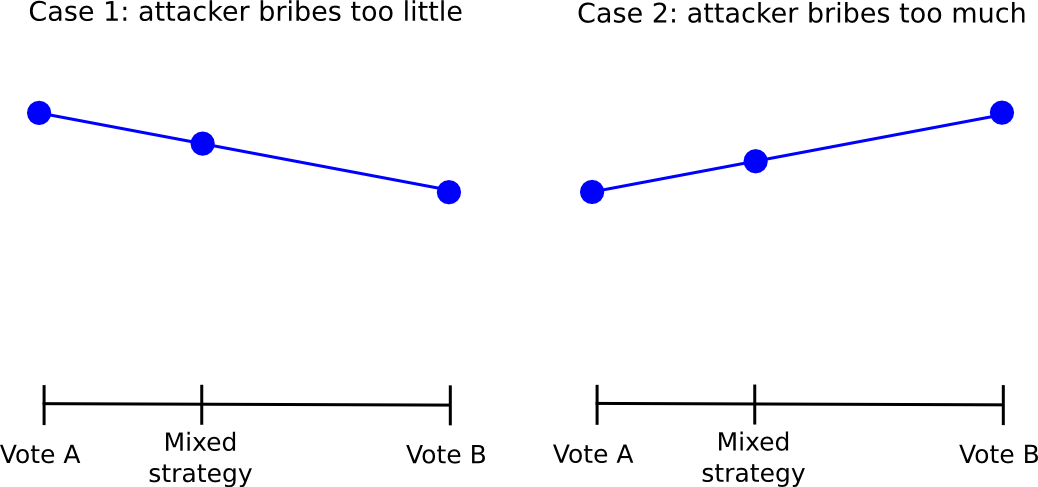

However, this approach itself suffers from the flaw that, if the attacker’s bribe is high enough, even from there one can defect. The fundamental problem is that given a probabilistic mixed strategy between A and B, for each the return always changes (almost) linearly with the probability parameter. Hence, if, for the individual, it makes more sense to vote for B than for A, it will also make more sense to vote with probability 0.51 for B than with probability 0.49 for B, and voting with probability 1 for B will work even better.

Hence, everyone will defect from the “49% for 1″ strategy by simply always voting for 1, and so 1 will win and the attacker will have succeeded in the costless takeover. The fact that such complicated schemes exist, and come so close to “seeming to work” suggests that perhaps in the near future some complex counter-coordination scheme will emerge that actually does work; however, we must be prepared for the eventuality that no such scheme will be developed.

Further Consequences

Given the sheer number of cryptoeconomic mechanisms that SchellingCoin makes possible, and the importance of such schemes in nearly all purely “trust-free” attempts to forge any kind of link between the cryptographic world and the real world, this attack poses a potential serious threat – although, as we will later see, Schelling schemes as a category are ultimately partially salvageable. However, what is more interesting is the much larger class of mechanisms that don’t look quite like SchellingCoin at first glance, but in fact have very similar sets of strengths and weaknesses.

Particularly, let us point to one very specific example: proof of work. Proof of work is in fact a multi-equilibrium game in much the same way that Schelling schemes are: if there exist two forks, A and B, then if you mine on the fork that ends up winning you get 25 BTC and if you mine on the fork that ends up losing you get nothing.

| You mine on A | You mine on B | |

| Others mine on A | 25 | 0 |

| Others mine on B | 0 | 25 |

Now, suppose that an attacker launches a double-spend attack against many parties simultaneously (this requirement ensures that there is no single party with very strong incentive to oppose the attacker, opposition instead becoming a public good; alternatively the double spend could be purely an attempt to crash the price with the attacker shorting at 10x leverage), and call the “main” chain A and the attacker’s new double-spend fork B. By default, everyone expects A to win. However, the attacker credibly commits to paying out 25.01 BTC to everyone who mines on B if B ends up losing. Hence, the payoff matrix becomes:

| You mine on A | You mine on B | |

| Others mine on A | 25 | 25.01 |

| Others mine on B | 0 | 25 |

Thus, mining on B is a dominant strategy regardless of one’s epistemic beliefs, and so everyone mines on B, and so the attacker wins and pays out nothing at all. Particularly, note that in proof of work we do not have deposits, so the level of bribe required is proportional only to the mining reward multiplied by the fork length, not the capital cost of 51% of all mining equipment. Hence, from a cryptoeconomic security standpoint, one can in some sense say that proof of work has virtually no cryptoeconomic security margin at all (if you are tired of opponents of proof of stake pointing you to this article by Andrew Poelstra, feel free to link them here in response). If one is genuinely uncomfortable with the weak subjectivity condition of pure proof of stake, then it follows that the correct solution may perhaps be to augment proof of work with hybrid proof of stake by adding security deposits and double-voting-penalties to mining.

Of course, in practice, proof of work has survived despite this flaw, and indeed it may continue to survive for a long time still; it may just be the case that there’s a high enough degree of altruism that attackers are not actually 100% convinced that they will succeed – but then, if we are allowed to rely on altruism, naive proof of stake works fine too. Hence, Schelling schemes too may well simply end up working in practice, even if they are not perfectly sound in theory.

The next part of this post will discuss the concept of “subjective” mechanisms in more detail, and how they can be used to theoretically get around some of these problems.

The post The P + epsilon Attack appeared first on .