Over the next few weeks, I am going to make a series of posts that is going to be a large overview of the possibilities for scalability of Ethereum, intending to create a precise understanding of the problems at bay in implementing a scalable cryptocurrency infrastructure, and where the least-bad tradeoffs and sacrifices required to solve those problems might lie. As a general outline of the form that this series is going to take, I intend to first discuss the fundamental problem with Ethereum 1.0 as it stands, as well as every other cryptocurrency platform in existence, and introduce limited solutions to specific problems that allow for much more efficiency in certain very specific use cases – in some cases increasing efficiency by a constant factor, and in other cases making a fundamental complexity-theoretic improvement, albeit a tightly-scoped one. In later posts, I will discuss further and further generalizations of such mechanisms, and finally culminating in the ultimate generalization: applying the tactics that I describe to make certain programs run better inside of Ethereum to Ethereum itself – providing at least one route to Ethereum 2.0.

Fundamentally, the problem of scaling up something like Bitcoin and Ethereum is an extremely hard one; the consensus architectures strongly rely on every node processing every transaction, and they do so in a very deep way. There do exist protocols for “light clients” to work with Ethereum, storing only a small part of the blockchain and using Merkle trees to securely access the rest, but even still the network relies on a relatively large number of full nodes to achieve high degrees of security. Scaling up to Visa or SWIFT levels of transaction volume is possible, but only at the cost of sacrificing decentralization as only a very small number of full nodes will survive. If we want to reach such levels, and go even higher with micropayments, we need to develop a consensus architecture which achieves a fundamental improvement over “every node processing every transaction”. However, as it turns out, there is a lot that we can do without going that far.

Protocol enhancements

Image from https://bitcoin.org/en/developer-guide

The first step in increasing space efficiency is some structural alterations to the protocol – alterations that have already been part of Ethereum since day one. The first is a shift from UTXO-based architecture to account-based architecture. The Bitcoin blockchain relies on a concept of “unspent transaction outputs” – every transaction contains one or more inputs and one or more outputs, with the condition that each input must reference a valid and unspent previous output and the total sum of the outputs must be no greater than the total sum of the inputs. This requires transactions to be large, often containing multiple signatures from the same user, and requires about 50 bytes to be stored in the database for every transaction that a node receives. It is particularly inconvenient when you have an account that very many people are sending small payments to; in the case of ethereum.org, it will take us hundreds of transactions to clear our exodus address.

Ripple and Ethereum instead use a more conventional system of transactions depositing to and withdrawing from accounts, ensuring that each account takes up only about 100 bytes on the blockchain regardless of its level of usage. A second protocol adjustment, used by both Ripple and Ethereum, is that of storing the full blockchain state in a Patricia tree in every block. The Patricia tree structure is designed to include maximal deduplication, so if you are storing many nearly-identical Patricia trees for consecutive blocks you only need to store most of the data once. This allows nodes to more easily “start from the middle” and securely download the current state without having to process the entire history.

These schemes are, of course, counterbalanced by the fact that Ethereum opens itself up to a wider array of applications and thus a much more active array of usage, and at the end of the day such optimizations can only go so far. Thus, to go further, we need to go beyond tweaks to the protocol itself, and build on top.

Batching

In Bitcoin, one transaction that spends ten previously unspent outputs requires ten signatures. In Ethereum, one transaction always requires one signature (although in the case of constructions like multisig accounts multiple transactions may be needed to process a withdrawal). However, one can go even further, and create a system where ten withdrawals only require one transaction and one signature. This is another constant-factor improvement, but a potentially rather powerful one: batching.

The idea behind batching is simple: put multiple sends into a single transaction in the data fields, and then have a forwarding contract split up the payment. Here is the simple implementation of such a contract:

i = 0 while i < msg.datasize: send(msg.data[i], msg.data[i+1]) i += 2 We can also extend it to support forwarding messages, using some low-level EVM commands in serpent to do some byte-by-byte packing:

init: contract.storage[0] = msg.sender code: if msg.sender != contract.storage[0]: stop i = 0 while i < ~calldatasize(): to = ~calldataload(i) value = ~calldataload(i+20) / 256^12 datasize = ~calldataload(i+32) / 256^30 data = alloc(datasize) ~calldatacopy(data, i+34, datasize) ~call(tx.gas - 25, to, value, data, datasize, 0, 0) i += 34 + datasize Instead of using your normal account to interact with contracts, the idea is that you would store your funds and maintain your relationships with contracts using this account, and then you will be able to make as many operations as you need all at once with a single transaction.

Note that this scheme does have its limits. Although it can arbitrarily magnify the amount of work that can be done with one signature, the amount of data that must be spent registering the recipient, value and message data, and the amount of computational resources that must be spent processing the transactions, still remains the same. The importance of signatures is not to be underestimated; signature verification is likely the most expensive part of blockchain validation, but the efficiency gain from using this kind of mechanism is still limited to perhaps something like a factor of four for plain old sends, and even less for transactions that involve a lot of computation.

Micropayment Channels

A common dream application of cryptocurrency is the idea of micropayments – having markets on very tiny chunks of computational or physical resources, paying for electricity, internet bandwidth, file storage, road usage or any other micro-meterable good one cent at a time. Existing cryptocurrencies are certainly useful for much smaller payments than were possible before; Paypal charges a fixed fee of $ 0.30 per transaction, and Bitcoin currently charges ~$ 0.05, making it logical to send payments as low as 50 cents in size. However, if we want to pay $ 0.01 at a time, then we need a much better scheme. There is no easy universal scheme to implement; if there was, that would be Ethereum 2.0. Rather, there is a combination of different approaches, where each approach is suited for a particular use case. One common use case is micropayment channels: situations where one party is paying the other over time for a metered service (eg. a file download), and the transaction only needs to be processed at the end. Bitcoin supports micropayment channels; Ethererum does as well, and arguably somewhat more elegantly.

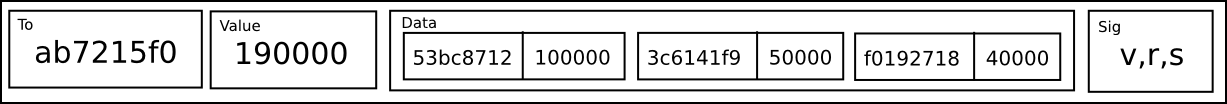

The channel works roughly as follows: the sender sends a transaction to initialize a channel, specifying a recipient, and the contract initializes a channel with value zero and supplies an ID for the channel. To increase the payment on the channel, the sender signs a data packet of the form [id, value], with value being the new value to transmit. When the channel process is done, and the recipient wants to cash out, he must simply take the signed [id, value, v, r, s] packet (the v,r,s triple being an elliptic curve signature) and push it to the blockchain as transaction data, and the contract verifies the signature. If the signature is valid, the contract waits 1000 blocks for a higher-valued packet for the transaction ID to be sent, and can then be pinged again to send the funds. Note that if the sender tries to cheat by submitting an earlier packet with a low value, the receiver has the 1000 block interval to submit the higher-valued packet. The code for the validator is as follows:

# Create channel: [0, to] if msg.data[0] == 0: new_id = contract.storage[-1] # store [from, to, value, maxvalue, timeout] in contract storage contract.storage[new_id] = msg.sender contract.storage[new_id + 1] = msg.data[1] contract.storage[new_id + 2] = 0 contract.storage[new_id + 3] = msg.value contract.storage[new_id + 4] = 2^254 # increment next id contract.storage[-1] = new_id + 10 # return id of this channel return(new_id) # Increase payment on channel: [1, id, value, v, r, s] elif msg.data[0] == 1: # Ecrecover native extension; will be a different address in testnet and live ecrecover = 0x46a8d0b21b1336d83b06829f568d7450df36883f # Message data parameters id = msg.data[1] % 2^160 value = msg.data[2] # Determine sender from signature h = sha3([id, value], 2) sender = call(ecrecover, [h, msg.data[3], msg.data[4], msg.data[5]], 4) # Check sender matches and new value is greater than old if sender == contract.storage[id]: if value > contract.storage[id + 2] and value <= contract.storage[id + 3]: # Update channel, increasing value and setting timeout contract.storage[id + 2] = value contract.storage[id + 4] = block.number + 1000 # Cash out channel: [2, id] elif msg.data[0] == 2: id = msg.data[1] % 2^160 # Check if timeout has run out if block.number >= contract.storage[id + 3]: # Send funds send(contract.storage[id + 1], contract.storage[id + 2]) # Send refund send(contract.storage[id], contract.storage[id + 3] - contract.storage[id + 2]) # Clear storage contract.storage[id] = 0 contract.storage[id + 1] = 0 contract.storage[id + 2] = 0 contract.storage[id + 3] = 0 contract.storage[id + 4] = 0 And there we go. All that is needed now is a decent off-chain user interface for processing the consumer-merchant side of the transaction.

Probabilistic Micropayments

But even still, micropayment channels are not a panacea. What if you only need to pay $ 0.007 to download a 32 MB file from someone, so even the entire transaction is not worth the single final transaction fee? For this, we do something slightly more clever: probabilistic micropayments. Essentially, a probabilistic micropayment occurs when a sender performs an action which provably has a specified probability of allowing a certain payment to happen in the future; here, we might do a 0.7% chance of paying $ 1. In the long term, both expenses and receipts will be roughly the same as in the non-probabilistic model, but with the benefit of saving 99% on transaction fees.

So, how do we do probabilistic micropayments? The general approach is to have the payment be a signed data packet of the form [nonce, timeout, to, value, prob], where nonce is a random number, timeout is a near-future block number, to is the recipient, value is the amount of ether to send and prob is the probability of sending multiplied by 232, and then when the block number surpasses timeout allow the data packet to be supplied to the blockchain and cashed out only if a random number generator, seeded with the nonce, supplies a value which mod 232 is less than prob.

Assuming a random number generator, the code snippet for the basic receiving function is:

# Cash out: [0, nonce, timeout, to, value, prob, v, r, s] if msg.data[0] == 0: # Helper contracts (addresses obviously won't work on testnet or livenet) ecrecover = 0x46a8d0b21b1336d83b06829f568d7450df36883f random = 0xb7d0a063fafca596de6af7b5062926c0f793c7db # Variables timeout = msg.data[2] to = msg.data[3] value = msg.data[4] prob = msg.data[5] # Is it time to cash out? if block.number >= timeout: # Randomness if call(random, [0, nonce, timeout], 3) % 2^32 < msg.data[5]: # Determine sender h = sha3(slice(msg.data, 1), 5) sender = call(ecrecover, [h, msg.data[6], msg.data[7], msg.data[8]], 4) # Withdraw if contract.storage[sender] >= value: contract.storage[sender] -= value send(to, value) There are two “hard parts” in the implementation of this approach. One is double-spending attacks, and the other is how to build the random number generator. To defeat double-spending attacks, the strategy is simple: require a very high security deposit in the contract alongside the account’s ether balance available for sending. If the sendable balance drops below zero, destroy the entire deposit.

The second part is, of course, how to build a random number generator in the first place. Generally, the main source of randomness used in Ethereum is block hashes; because micropayments are low-value applications, and because the different nonce on each transaction ensures that a block hash is extremely unlikely to favor any particular user in any particular way, block hashes will likely be sufficient for this purpose – however, we need to make sure we grab a specific block hash rather than simply the block hash when a request is sent (using the block hash when a request is sent also works, but less well, since the sender and receiver have an incentive to try to disrupt each other’s attempts to send claim transactions during blocks that are unfavorable to them). One option is to have a centralized contract maintain a list of the block hash for every block, incentivizing miners to ping it every block; the contract can charge a micropayment for its API in order to pay for the service. For efficiency, one can limit the contract to providing a reward once every ten blocks. In the event that the contract skips over a block, the next block hash is used.

The code for the one-every-ten-blocks version is:

# If we get pinged for the first time in a new epoch, set the prevhash if !contract.storage[block.number / 10]: send(msg.sender, 10^17) contract.storage[block.number / 10] = block.prevhash # Otherwise, provide the block hash: [0, block number] if msg.data == 0 and msg.value > 10^16: return(contract.storage[msg.data[1] / 10]) In order to convert this into a suitable implementation of the random contract, we just do:

# If we get pinged for the first time in a new epoch, set the prevhash if !contract.storage[block.number / 10]: send(msg.sender, 10^17) contract.storage[block.number / 10] = block.prevhash # Otherwise, provide the hash of the block hash plus a nonce: [0, block number, nonce] if msg.data == 0 and msg.value > 10^16: return(sha3([contract.storage[msg.data[1] / 10], msg.data[2]], 2)) Note that for something like this to work efficiently, one “higher-level” piece of infrastructure that needs to exist is some kind of incentivized pinging. This job can be done cooperatively with a pub/sub contract: a contract can be made which other contracts subscribe to, paying a very small fee, and when the contract gets pinged for the first time in N blocks it provides a single reward and immediately pings all of the contracts that subscribed to it. This strategy is still vulnerable to some abuse by miners, but the low-value nature of micropayments and the independence of each payment should limit the problem drastically.

Off-chain oracles

Following the spirit of signature batching, an approach that goes even further is to take the entire computation off the blockchain. In order to do so securely, we use a clever economic hack: the code still goes on the blockchain, and gets recorded there, but by default the computation is decided by oracles which run the code off-chain in a private EVM and supply the answer, also providing a security deposit. When the answer is supplied, it takes 100 blocks until the answer is committed; if everything goes well, the answer can be committed to the blockchain after 100 blocks, and the oracle recovers its deposit and a small bonus. However, within that 100-block interval, any node can check the computation themselves, and if they see that the oracle is wrong they can pay for an auditing transaction – essentially, actually run the code on the blockchain, and see if the result turns out to be the same. If it does not, then the auditor gets 90% of the block reward and the other 10% is destroyed.

Essentially, this provides near-equivalent assurances to every node running the code, except that in practice only a few nodes do. Particularly, if there is a financial contract, the parties to the financial contract have a strong incentive to carry out the audit, because they are the ones who would be screwed over by an invalid block. This scheme is elegant, but somewhat inconvenient; it requires users to wait 100 blocks before the results of their code can be used.

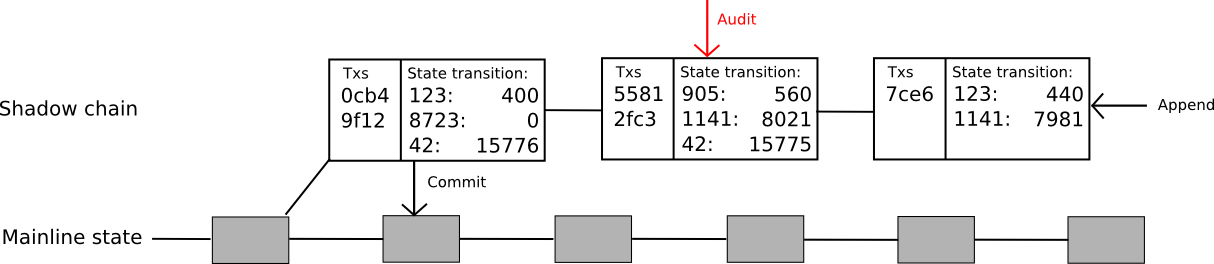

To solve that problem, the protocol can be extended even further. Now, the idea is to create an entire “shadow chain”, with computations happening off-chain but state transitions being committed back to the main chain after 100 blocks. Oracles can add new blocks to the “tail” of the chain, where a block consists of a list of transactions and a [[k1, v1], [k2, v2] ... ] list of state transitions caused by those transactions. If a block is unchallenged for 100 blocks, the state transitions are applied automatically to the main chain. If the block is successfully challenged before it is committed then that block and all children are reverted, and the block and all children lose their deposits with part going to the auditor and part to the void (note that this creates extra incentive to audit, since now the author of the child of a shadow block would prefer to audit that shadow block lest they be caught up in the author’s potential malfeasance). The code for this is much more complicated than the other examples; a complete but untested version can be found here.

Note that this protocol is still a limited one: it solves the signature verification problem, and it solves the state transition computation problem, but it still does not solve the data problem. Every transaction in this model must still be downloaded by every node. How do we do even better? As it turns out, we probably can; however, to go further than this we have to solve a much larger problem: the problem of data.

The post Scalability, Part 1: Building on Top appeared first on ethereum blog.