The DAO – Revisited

Abstract: In this piece we revisit “The DAO” and the events following its failure. We analyse what happened to the various buckets of funds inside The DAO, on both sides of the chainsplit which it caused. We identify US$140 million of unclaimed funds still inside what is left of The DAO.

Key points

- The DAO hacker appears to control tokens worth approximately US$60 million.

- There are currently around US$140 million of unclaimed funds still inside The DAO withdrawal contracts.

- In June 2017, the US Dollar value of funds unclaimed inside The DAO was higher than the value of the amount initially raised in May 2016.

- A deadline is approaching, 10 January 2018, after which some of the funds, around US$26 million, may no longer be available to be claimed.

The DAO marketing material from May 2016

Source: DaoHub

Overview

In the early summer of 2016, one project generated a substantial amount of excitement and buzz in the crypto space, “The DAO”. DAO stands for Decentralized Autonomous Organization, and to the confusion of many, “The DAO” consumed that entire moniker for itself. The DAO was to be an autonomous investment fund, investing in projects determined by the token holders. The fund was to be governed by a “code is law” philosophy, as opposed to the centralized top down control mechanisms in traditional investment funds, where key individuals matter.

Many believed this novel approach would lead to superior investment returns. Although it is a unique and potentially interesting approach, in our view, expecting strong investment returns at this point may be somewhat naive.

The fund raised Ethereum tokens worth approximately US$150 million at the time, around 14% of all the ether in existence, with investors presumably expecting spectacular returns. The downside risk was expected to be minimal or zero, since one was supposed to be able to withdraw one’s Ethereum from The DAO, whenever one wished. In reality, doing so was a complex and error-prone process.

Problems with The DAO

As it turns out, The DAO was fundamentally flawed on several levels, as many in the Ethereum Foundation pointed out before the exploit was discovered. For instance:

- Economic Incentives – The incentive model of the project was poorly thought out. For example there was little incentive to vote “no” on investment proposals, since “no” voters became invested in approved projects. Those that did not vote did not become exposed to the project. Additionally, there was no stated enforcement mechanism for successful projects to contribute profits back into The DAO.

- Token viability – When projects were created, it would have end up creating new classes of DAO tokens, such that each class was entitled to different risks and rewards. This would mean the tokens would not be fungible, an issue poorly understood by exchanges and the community.

- Buggy code – The code did not always implement what was described or intended. The smart contract code did not appear to be reviewed adequately. The coders did not appear to fully grasp its language, Solidity, nor some of the states the contract could reach.

A few weeks after the conclusion of the token sale, a “hacker” managed to find an exploit in the code, enabling them to potentially access The DAO’s funds, by draining the main pool of funds into a child DAO in which the hacker potentially had significant control. This then led to an Ethereum hardfork, to attempt to prevent the hacker from accessing the funds and to return the funds to the initial investors. Since some in the Ethereum community were unhappy about this, it lead to the chain split between ETH and ETC.

In this piece we will:

- Describe the relationships between the main actors involved in The DAO,

- Revisit the key events surrounding Ethereum’s DAO hardfork,

- Explore the movement of ETH and ETC funds inside The DAO, and

- Speculate on what will happen to the unclaimed funds.

The main groups and individuals related to The DAO

Network map of the main groups and the individuals involved in The DAO

Sources: BitMEX Research, Full sources provided in the table below

Notes: There are other Ethereum foundation members with no association to The DAO, which are excluded from the above mapping. Blue circles represent individuals; while yellow circles represent organisations.

List of the major parties involved in The DAO

| Name | Description | People involved |

| DAOHub.org | A DAO community website promoting The DAO, hosted by DAO.Link | Felix Albert , Auryn Macmillan, Boyan Balinov, Arno Gaboury, Michal Brazewicz , Taylor Van Orden , Des Donnelly, Daniel McClure (Source) |

| Slock.it | Slock.it wrote the code for The DAO and the company was hoping to develop smart locks. Slock.it was expected to be financed by The DAO | Stephan Tual, Lefteris Karapetsas, Griff Green, Christoph Jentzsch, his brother Simon Jentzsch, Gavin Wood and Christian Reitwießner (Source) |

| The “Hacker” | The exploiter of The DAO | Anonymous |

| DAO Token Holders (DTH) | Individuals from the general public who contributed to The DAO crowdsale or purchased DAO tokens on the open market | 22,873 account holders (Source) |

| The DAO Curators | 3rd party “arbitrators” separate from Slock.it to manage disputes or emergency situations arising from The DAO | Taylor Gerring, Viktor Tron, Christian Reitwießner, Gustav Simonsson, Fabian Vogelsteller, Aeron Buchanan, Martin Becze, Vitalik Buterin, Alex Van de Sande, Vlad Zamfir and Gavin Wood (Source) Note: Gavin Wood resigned as a DAO Curator prior to the exploit |

| Bity | A Swiss based cryptocurrency exchange in partnership with Slock.it. The exchange publishes WHG announcements (Source) | Alexis Roussel (Source) |

| DAO.Link | A Swiss registered joint venture company between Slock.it and Bity, which hosts the DAOHub website (The website promoting The DAO, pictured above) | Stephan Tual, Simon Jentzsch, Alexis Roussel (Source) |

| Robin Hood Group (RHG) | The original “white hat” group, which secured the majority of The DAO funds pre-fork | Publicly: Alex Van de Sande, Griff Green, Lefteris Karapetsas Stephan Tual claims: “individuals from the eth foundation, devs, security experts, ethcore, slock, etc” (Source) |

| Whitehat Group (WHG) | The organisation which took ownership of ETC from the RHG. The WHG has close ties to Bity | Only publicly known members are Jordi Baylina and Griff Green (Source) |

| The Ethereum Foundation | Non profit foundation behind the creation of Ethereum | Many individuals including some of the founders of Ethereum (Source) |

The DAO timeline

In order to fully understand and account for the proper ownership of the funds, we must revisit the provenance of The DAO funds before, during and after the hardfork.

| Date | Event | Movement of Funds |

| 30 April 2016 | The DAO crowdsale is launched (Source: Slock.it) | |

| 25 May 2016 | The DAO crowdsale concludes | c11.5 million pre-fork ETH raised |

| 17 June 2016 | The DAO is drained into a Child DAO by the hacker (Source: New York Times) |

c3.6 million pre-fork ETH drained to Hacker’s Child DAO |

A “Child DAO” can be “split” from the main DAO as part of the The DAO’s governance process, similar to a spin-off company.

The splitting process was exploited by the hacker using a recursive call exploit, which drained more funds from the parent DAO than intended. The owner of a newly formed Child DAOs cannot withdraw those funds immediately; they have to wait for a voting period to end before securing those funds and being able to freely transfer them.

This voting period gave the Ethereum community a window of opportunity to attempt to reclaim the funds by attempting to exploit the hacker’s Child DAO using the same vulnerability. This, however, may have resulted in perpetual splitting and a “DAO War”, whereby the funds would be stuck in limbo forever as long as neither the hacker nor RHG gave up. This process could be easily scripted so would not take much effort on either side.

One way to solve this would be the implementation of a softfork to censor the hacker’s transactions, preventing him/her from participating in this war and quickly allowing the funds to be recovered.

| Date | Event | Movement of Funds |

| 21 June 2016 | RHG begin “DAO Wars” and are able to to recover a majority of the funds (Source: Reddit) |

c8.1 million pre-fork ETH Drained into the RHG’s Child DAOs using the same vulnerability |

| 24 June 2016 | “DAO Wars” softfork proposed to secure attacker’s c3.6 million pre-fork ETH (Source: Ethereum Foundation) |

Would have censored transactions to prevent hacker from accessing their Child DAO |

| 28 June 2016 | Critical flaw in “DAO Wars” softfork discovered and it is abandoned (Source: Hacking Distributed) |

At this point, the RHG have managed to secure around 70% of the funds by exploiting other Child DAOs, but in order to guarantee the ability to reclaim the remaining 30% (around 3.6 million pre-fork ETH), a hardfork is the only possibility. Moreover, the softfork proposal was found to have critical security vulnerabilities and was quickly scrapped.

| Date | Event | Movement of Funds |

| 20 July 2016 | Hardfork is implemented, effectively undoing the effects of The DAO hack and making DTH whole on the forked ETH chain. Implemented via two withdrawal contracts. (Source: Ethereum Foundation, The Ethereum Wiki) |

c11.5 million post-fork ETH returned to DAO withdraw contract and can be claimed by DTH based on their current DAO token balances |

| 20 July 2016 | ETC, the ‘not-forked’ chain continues to be mined | The RHG and The DAO hacker will eventually have access to ETC in Child DAOs |

After the fork, there are two chains in parallel universes. One, ETH, where the hack is undone, and one ETC, where the hack remains. The RHG have still secured around 70% of the ETC, and could have continued the attack on the ETC chain using the aforementioned ‘DAO wars limbo’ strategy, but decide not to. To refund DTH on the ETH chain, a withdrawal contract is used, which DTH must call to claim their ETH.

| Date | Event | Movement of Funds |

| 23 July 2016 | ETC is listed on Poloniex, other exchanges follow suit. ETC/USD reaches 1/3 of ETH/USD (Source: Twitter) |

n/a |

| 9 Aug 2016 | The RHG hands ownership of the ETC funds to the WHG. The WHG receive funds in their ETC multisig wallet as the ETC Child DAOs mature (Source: Bity) |

c8.1 million ETC Secured by the WHG |

| 10 Aug 2016 | Unannounced, WHG/Bity use Bity’s “verified money service business” account to attempt to tumble and swap 3 million ETC on 4 exchanges for ETH, BTC and EUR (Source: Bity) |

Poloniex freezes 2.3 million ETC, Kraken trades but freezes 1.3 million worth of ETC, Bittrex trades and processes 82k ETC, Yunbi trades and processes 101k ETC |

| 12 Aug 2016 | After the majority of the tumbled ETC is frozen, WHG/Bity announce that they have decided not to sell the ETC for ETH, and instead will distribute ETC to DTH (Source: Reddit) |

Bity trade back BTC, ETH and EUR into c1.5 million ETC, bringing their balance back to c8.1 million ETC |

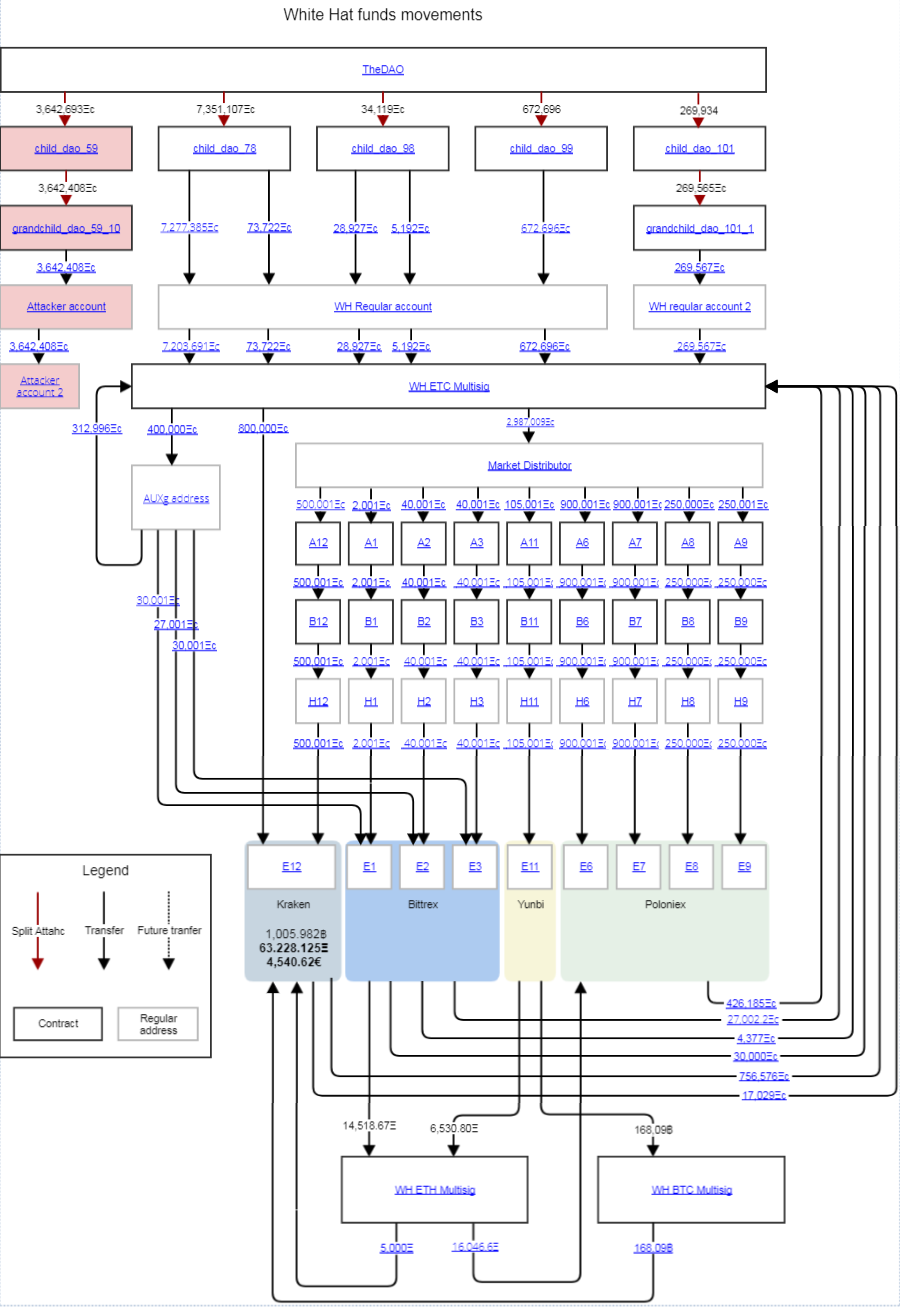

Graphical illustration of the above transactions

Source: Gliffy

| Date | Event | Movement of Funds |

| 26 Aug 2016 | Bity announce launch of the “Whitehat Withdrawal Contract” (Source: Bity) |

n/a |

| 30 Aug 2016 | Bity announce that the first version of “Whitehat Withdrawal Contract” is published (Source: Bity) |

c4.2m ETC transferred from WHG to the withdrawal contract, c0.6 million claimed by DTH. DTH are entitled to receive funds based on their DAO token balance at the time of the harfork, not the current token balance as is the case for ETH. |

| 30 Aug 2016 | Bity announce that second version of “Whitehat Withdrawal Contract” is published (Source: Bity) |

c3.8 million ETC transferred from old contract to new contract |

| 6 Sept 2016 | Bity announce that the remaining ETC (including that which was attempted to be traded on exchanges, and some from matured Child DAOs) is transferred to the Whitehat Withdrawal Contract (Source: Bity) |

c4.3 million ETC transferred from WHG exchange accounts and multisig into withdrawal contract.

During the time these trades were made, the price of ETC dropped in value relative to ETH, BTC and/or EUR, causing the trade back into ETC to yield an additional 700,000 of ETC that was added to the Whitehat Withdrawal Contract. The exact details of these on-exchange swaps were not made public. |

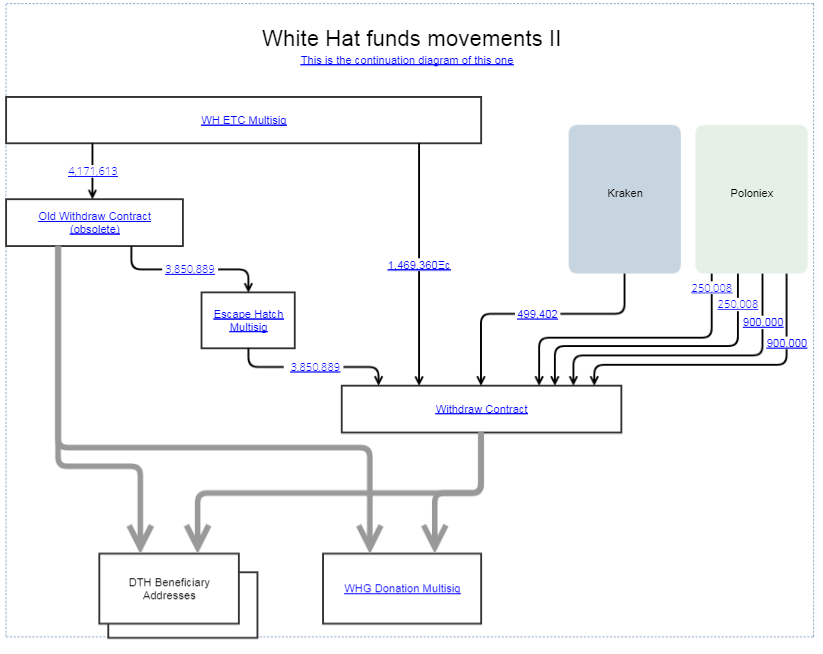

Graphical illustration of the above transactions

Source: Gliffy

| Date | Event | Movement of Funds |

| 6 Sept 2016 | DAO Hacker moves the funds from his “Dark Child DAO” (Source: Gas Tracker) |

c3.6 million ETC Secured by Hacker |

| 6 Sept 2016 | DAO Hacker donates some ETC to the ETC development fund (Source: Gas Tracker) |

1,000 ETC sent to ETC developer fund |

| 25 Oct 2016 to 7 Dec 2016 |

DAO Hacker tumbles funds into many different accounts, potentially swapping to different currencies (Source: Gas Tracker) |

c0.3 million ETC tumbled by hacker |

At the time of writing the hacker has not touched the vast majority of the drained ETC, and is sitting on a stash of 3,360,332 ETC, worth US$58 million.

One feature of the Whitehat Withdrawal Contract is that a limit is set for the ETC funds to be withdrawn (originally set to 3 months, expiring on 30th January 2017). Due to a large proportion of the funds not being claimed within the 3 months given, this period was extended twice:

| Date | Event | Movement of Funds |

| 30 Jan 2017 | Bity Announce the extension of the ETC Whitehat Withdrawal contract deadline to 14 April 2017 (Source: Bity) |

n/a |

| 14 April 2017 | RHG Announce the extension of the ETC Whitehat Withdrawal contract deadline to 10 January 2018 (Source: Reddit) |

n/a |

| 10 Jan 2018 | ETC Whitehat Withdrawal contract deadline | ? |

There have been no major events since then to the present day; the vast majority of ETH funds have been withdrawn by DTH, as has the majority of ETC.

The unclaimed funds

As at 19th November 2017, there is approximately US$140 million of unclaimed funds, as the approximate breakdown below illustrates.

DAO related funds on the ETH side of the fork

| Bucket | ETH | Unclaimed US$ million | Percent |

| Claimed balances | |||

| ETH Withdrawn by DTH | 11,286,046 | 97.3% | |

| Unclaimed balances | |||

| Unclaimed ETH in DAO Withdraw (Source) | 235,414 | 86.6 | 2.0% |

| Unclaimed ETH in DAO ExtraBalance (Source) | 76,204 | 28.0 | 0.7% |

| Unclaimed total | 311,618 | 114.7 | 2.7% |

| Claimed & unclaimed | |||

| Total funds | 11,597,664 | 100.0% | |

Source: BitMEX Research, Ethereum blockchain

Note: USD/ETH price of $368 used

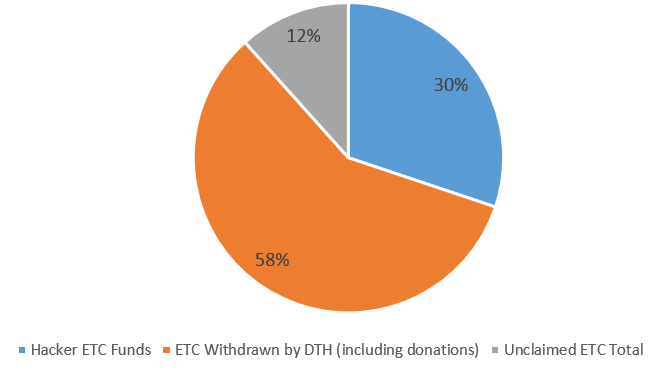

DAO related funds on the ETC side of the fork

| Bucket | ETC | US$ million | Percent |

| Hacker funds | |||

| ETC retained by Hacker | 3,642,408 | 66.6 | 30.1% |

| WHG Funds | |||

| ETC Withdrawn by DTH (including donations) | 7,035,319 | 58.2% | |

| Unclaimed ETC (Source) | 1,405,072 | 25.8 | 11.6% |

| WHG Total | 8,440,391 | 100.0% | |

| Hacker & WHG funds | |||

| Total funds | 12,082,799 | ||

Source: BitMEX Research, Ethereum Classic blockchain

Note: USD/ETC price of $18.30 used

DAO related funds on the ETC side of the fork

Source: BitMEX Research, Ethereum Classic blockchain

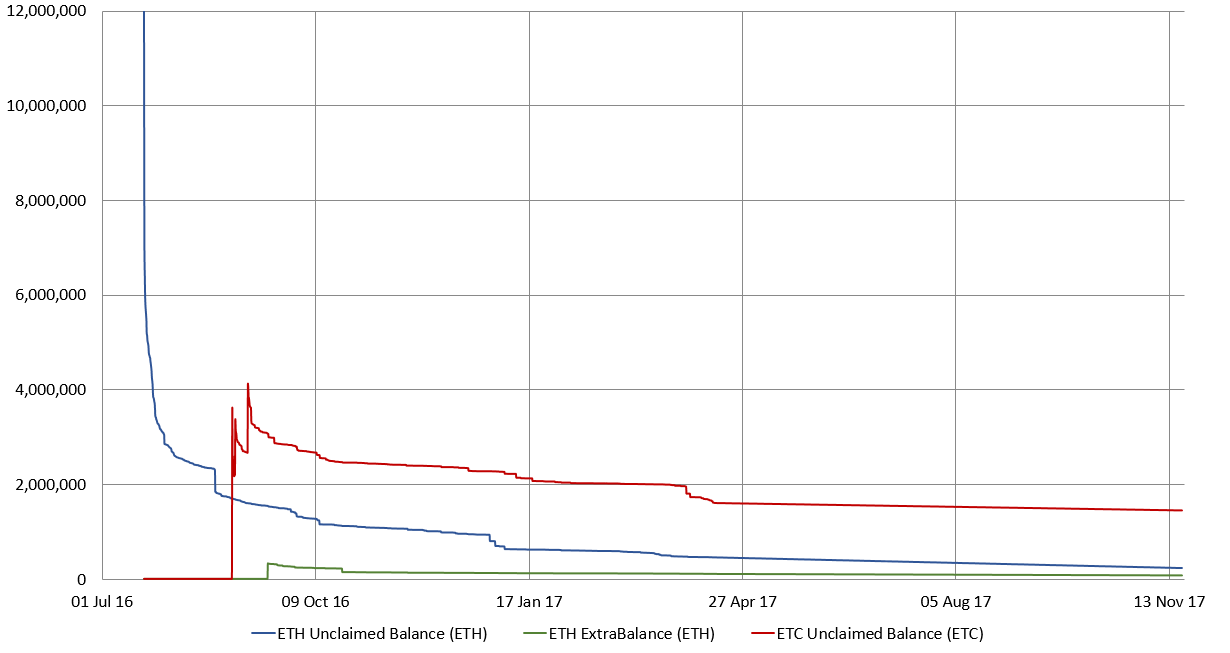

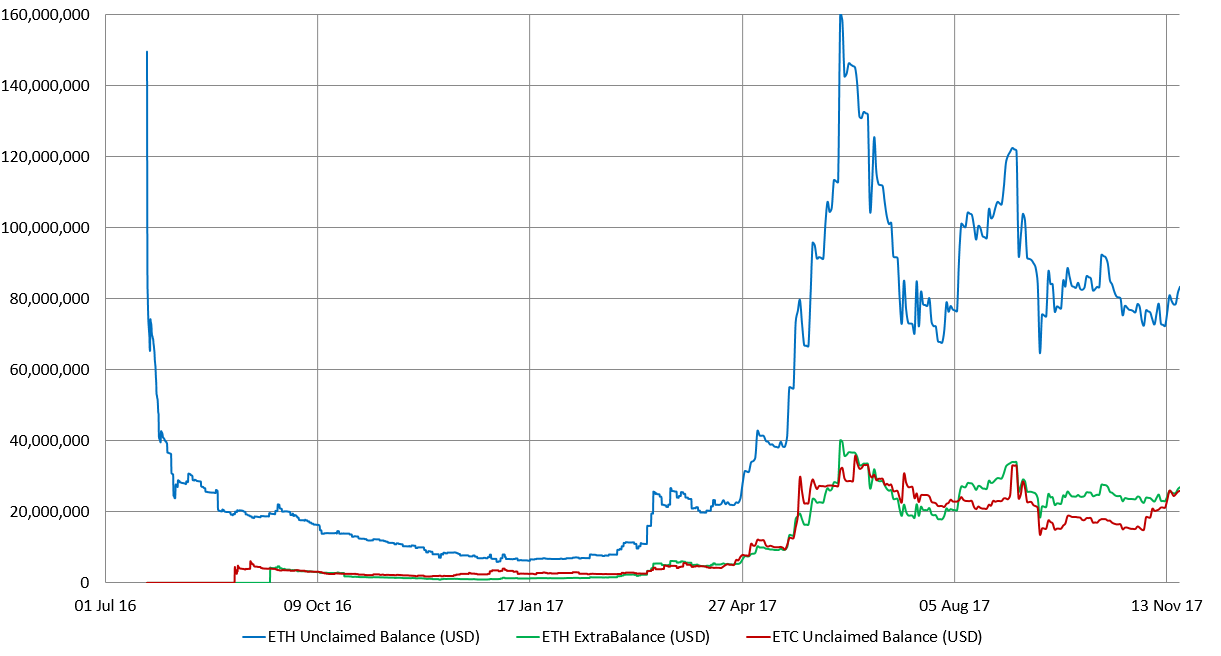

Unclaimed DAO balances over time – ETH & ETC

Source: BitMEX Research, Github

Unclaimed DAO balances over time – USD

Source: BitMEX Research, Coinmarketcap, Github

As the chart above illustrates, at the Ethereum price peak in July 2017, the US Dollar value of unclaimed Ethereum inside DAO withdrawal contracts was even higher than the US$150 million initially raised.

Withdrawal Contract “Gotchas”

Whilst the notion of a withdrawal contract sounds binding, all of the unclaimed funds are still in the control of the owners of those contracts.

Safety Hatches

All of the three withdrawal contracts have ‘safety hatch’ mechanisms, meaning the ‘owners’ of these contracts have the ability to withdraw all of the funds at any time.

- DAO Withdraw & DAO ExtraBalance owner: DAO Curators Multisig

- The Whitehat Withdrawal Contract owner: WHG Address

Whilst The DAO Curators have not indicated this is planned, it may be tempting to appropriate these funds if it is deemed that no more withdrawals will take place. The WHG, in contrast, have designed their contract specifically to ensure this happens.

Whitehat Deadline

The Whitehat Withdrawal contract also has a timeout system for when DTH are able to withdraw their funds. This deadline will expire on January 10th 2018 (although it has been extended twice before), so attempts to withdraw after this deadline may be denied.

What next for the US$26 million of unclaimed ETC?

The next obvious question is:

What happens to the unclaimed funds on January 10th 2018?

There are four clear options at present:

- Have WHG/Bity keep the funds as payment for their service, returning some of the ETC

- Donate the funds to a charity or the “community”, perhaps the ETC, DTH or ETH community

- Extend the deadline again

- Commit to allowing withdrawals indefinitely, as with the ETH withdrawal contracts

An official response from Bity, suggested they may lean towards option two:

We feel that these funds should be donated to the DAO Token holders community where they originated from. After 6 months, we want to be able to donate these unclaimed funds to a community wide effort, like a foundation supporting smart contracts security. We want these funds to be used to develop the future of structures of Decentralized Governance, DAOs and smart contracts. We will see what options are available at the time.

Source: Bity

Of course, questions of who represents the ‘DTH Community’ will arise, and whether or not the funds are being spent in a transparent matter may come into question. Due to the anonymous nature of who is behind WHG, it may be difficult for the community to properly audit the spending of these unclaimed funds.

Additionally, this arbitrary timeline that prevents individuals in the future from claiming funds that are rightfully theirs may result in future legal action. As such, there is a possibility that WHG is only left with option 3 or 4, and will potentially allow ETC withdrawals to continue in perpetuity.

However, January 2018 will be over 18 months after The DAO, a long time in the crypto space. In addition to this the price of both ETH and ETC has risen considerably since The DAO. Therefore perhaps some DTHs may forget about their tokens in all the excitement and wealth generation, which is prevalent in the Ethereum ecosystem.

Disclaimer

Whilst many claims made in this note are cited, we do not guarantee accuracy. We welcome corrections.

Hinterlasse einen Kommentar

An der Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlasse uns deinen Kommentar!