The Money Is Gone

After a stock analyst lost $1 million on one penny stock, he set off to find out how — and soon discovered signs of a far bigger scheme than he had ever imagined.

Quelle: theintercept | The Money Is Gone

Chris DiIorio had just lost a million dollars.

This was back in 2006. DiIorio, who was 39 at the time, had recently moved with his new wife from Boston to Castle Pines, Colorado, a leafy suburb of Denver, and was toiling in finance as a market researcher, analyzing the financial statements of public companies and giving recommendations to portfolio managers.

He had previously worked on Wall Street as an institutional equity trader and research analyst for a subsidiary of the now-defunct investment bank Donaldson, Lufkin, and Jenrette. He had 13 years experience executing massive trades for large mutual fund clients like Fidelity and Putnam.

Matt Slaby for The Intercept

Chris DiIorio

But in his new life, DiIorio happened upon a technology company called E Mobile (symbol: EMTK), a small computer chipmaker that claimed to hold patents on an antenna-type Wi-Fi router and other products. He reviewed company press releases, as well as investor chatter online claiming that E Mobile’s chips were provoking interest from Chinese content companies.

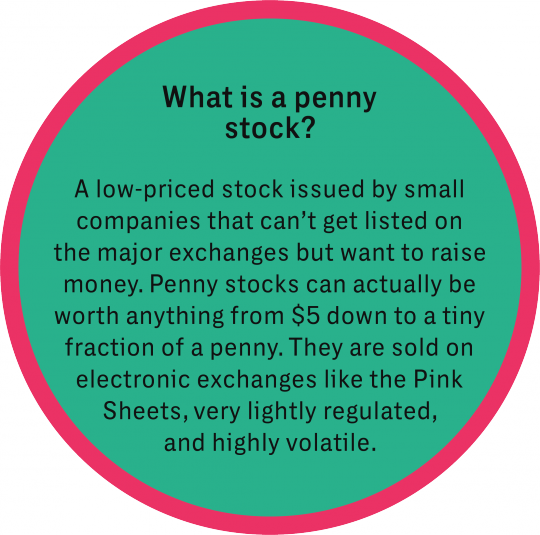

E Mobile didn’t trade on the New York Stock Exchange or Nasdaq, however. It was an over-the-counter stock, traded on an electronic exchange called the Pink Sheets that is home to what are commonly called “penny stocks.”

A penny stock is actually any equity that trades for $5 a share or less. But many shares can be had for a literal penny, or even a fraction of one. They are purchased on the Pink Sheets and the over-the-counter Bulletin Board market, through your regular brokerage account.

Not every penny stock is suspect; some are simply startup companies working their way to larger exchanges. But they do lurk on the dark edges of the financial markets, with sudden volumes and massive volatility. Regulation and reporting vary from light to nonexistent.

“They don’t have the same standards,” said Joseph Borg, director of the Alabama Securities Commission, who achieved fame by investigating Jordan “The Wolf of Wall Street” Belfort’s company Stratton Oakmont for penny stock fraud in the 1990s. “Willie Sutton said he robbed banks because that’s where the money is. This is the easiest place to manipulate something.”

The Pink Sheets’ own website warns that it “offers trading in a wide spectrum of securities” and that “With no minimum financial standards, this market includes foreign companies that limit their disclosure, penny stocks and shells, as well as distressed, delinquent, and dark companies not willing or able to provide adequate information to investors. As Pink requires the least in terms of company disclosure, investors are strongly advised to proceed with caution and thoroughly research companies before making any investment decisions.”

But DiIorio didn’t know that at the time.

On Wall Street, he had executed multimillion share trades, usually of blue chip companies that make up the Dow Jones Industrial Average, like IBM or General Electric.

“I had never invested in a penny stock before,” DiIorio said. “I was not super sophisticated in this world.” But he decided to take a flyer on E Mobile, based on its promising news. “I bought this company on hype.”

Between February and May 2005, DiIorio bought over 3.7 million shares of E Mobile, mostly through his rollover IRA account with TD Ameritrade. The total cost: $100,000, or a little over 3 cents a share. It was a big position, but this was retirement money he was trying to grow, and if it paid off, the payday would be tremendous.

E Mobile bounced around for a year, not doing much. The CEO, Nan Hu, personally called DiIorio, asking him to invest more through a “private placement”: an off-market offering of stock to select investors.

DiIorio declined. “I was already up to my eyeballs. I said, ‘I’m good with my position.’” Attempts to reach Hu for comment were unsuccessful.

Then, in March 2006, E Mobile announced a “reverse merger” with Best Rate Travel, a private company specializing in online vacation booking. Adrian Stone replaced Hu as CEO. To DiIorio, it was a puzzling maneuver for a chipmaker. “They announced a merger with a travel company?” he said. “What the fuck?”

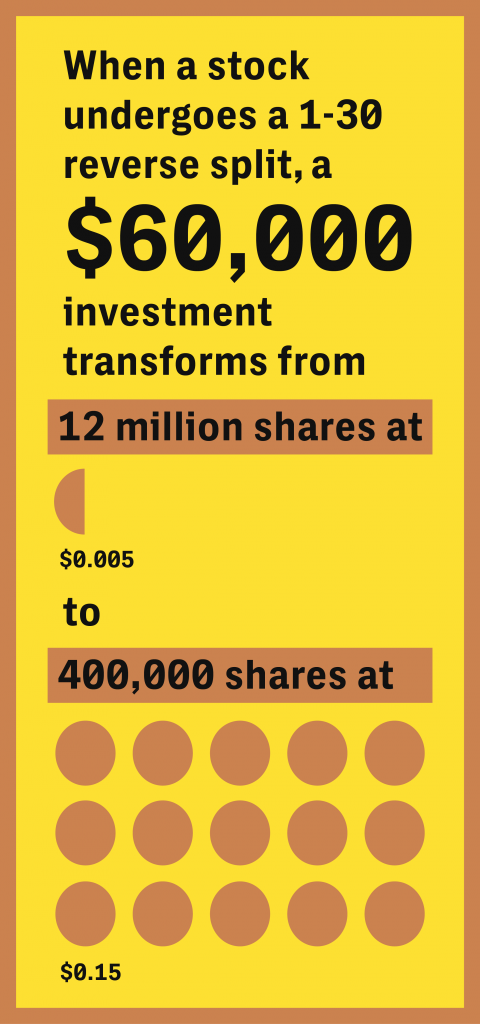

As part of the merger, E Mobile changed its name to Best Rate Travel, altered its stock ticker symbol to BTVL, and did a 1-1,000 “reverse stock split.”

You’ve probably heard of a stock split; it can happen when a company’s share price gets unmanageably high. So when a stock hits, say, $200, investors who owned one share receive two, each priced at $100.

Well, the opposite can happen, too. Best Rate Travel’s reverse split gave existing investors like DiIorio way fewer shares — at a way higher price.

As a major shareholder, DiIorio was offered a slightly better deal: a conversion to preferred shares of E Mobile at a lower reverse split rate of 1-to-30, and then a conversion at 3-to-1 to Best Rate Travel. After all that, he was left with 373,599 BTVL shares.

The merger hype, repeated in a feedback loop of positive press releases, moved the stock. DiIorio recalls it peaking at $3.50 by September 2006, giving his holdings a value of around $1.3 million.

“I thought this was the exception to everything I knew about the markets,” DiIorio said. “Cheap stocks are cheap for a reason.” But the success fed DiIorio’s ego. He felt like he beat the odds, vindicating his stock-picking acumen.

There was a problem, however. Best Rate Travel structured the conversion with a “lock-up” agreement, restricting shareholders like DiIorio from selling the stock for a year. This is common for newly public companies.

But it left DiIorio helpless when the stock plummeted from $3.50 to $0.06 a share within two months.

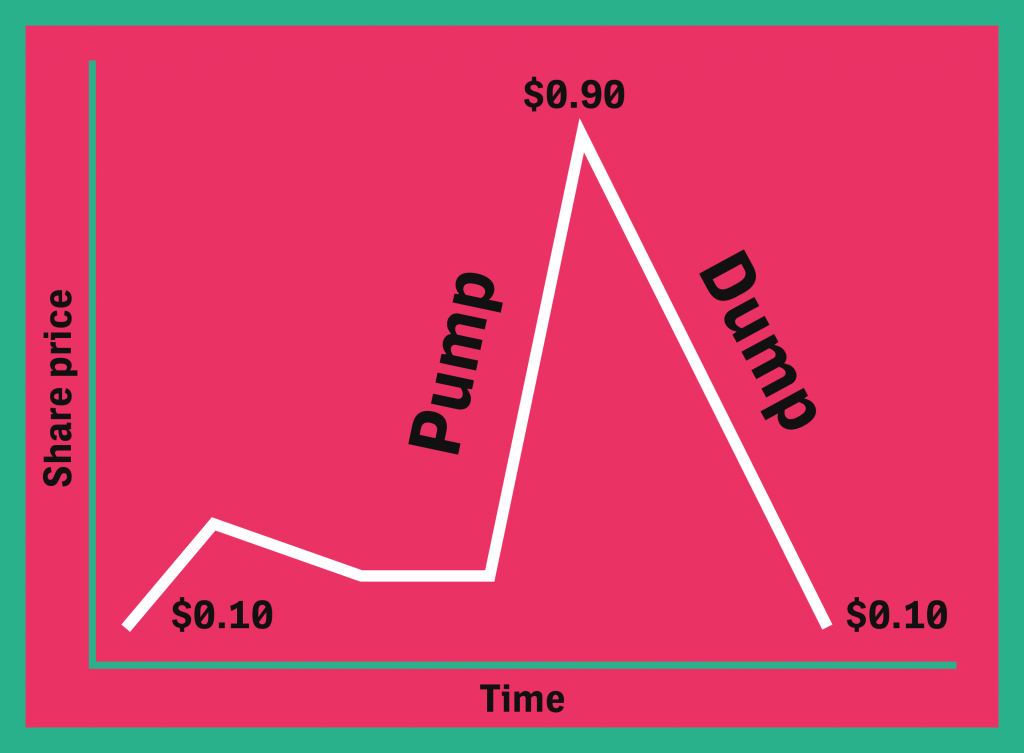

DiIorio initially saw it as a classic “pump-and-dump” scheme, where major investors in a company lure in other investors with overhyped claims, raising the stock price, and then sell their shares, leading to a drop. Pump-and-dumps have proliferated with the rise of internet message boards. “It’s not just promoters calling you on the phone anymore,” said Laura Posner, bureau chief of the New Jersey Bureau of Securities. “People pretend to be other people, pretend to have inside information.”

But to DiIorio, BTVL’s drop didn’t make sense, because prior shareholders were prohibited from trading the stock. “I called the CEO regularly and said: ‘Who’s selling the stock? How is this happening? The stock is not for sale.’ He told me that he was locked up too.” Phone numbers and email addresses listed for CEO Adrian Stone no longer function, so he could not be reached for comment.

By the end, DiIorio took a loss from the peak stock value of well over $1 million. “I never saw such devastation in a stock before,” he said.

In a pump-and-dump scheme, investors buy a stock, hype it to pump up its value, then dump it before it crashes back down.

Graphic: The Intercept

A Real Head-Scratcher

DiIorio prided himself on being a savvy trader.

And the implosion of Best Rate Travel, given the lock-up period, shouldn’t have occurred. DiIorio wanted to understand what really happened to crush his investment so completely. And he had the background in financial market analysis to see it through.

So DiIorio started learning what firms traded Best Rate Travel. The biggest two by far were the giant Swiss bank UBS and a massive New Jersey-based company named Knight Capital.

He thought these were very big names to be involved in such an obscure penny stock.

Something fishy was going on, but DiIorio had no idea what. “I just thought, what the hell, I’m going to figure this out.”

For one thing, there were two huge companies involved.

UBS, one of the world’s largest private banks, seemed to have no business trading in penny stocks. “This was a $50 billion-plus bank, it didn’t seem like penny stocks would move the needle,” DiIorio said. But just in December 2011, UBS’s trades in 32 penny stocks represented over half of the firm’s total share volume, according to his calculations.

In a one-line response to a series of detailed questions from The Intercept, UBS media relations director Peter Stack wrote in an email: “UBS applies strict due diligence and anti-money-laundering standards to all its business.”

After some research, DiIorio became even more disturbed by the presence of the other company, Knight Capital, which has traded an average of more than 2 billion shares of penny stocks daily for the past three years.

Based in Jersey City, N.J., Knight is what is called a “market maker,” a dealer that facilitates trading by actually holding shares itself, if ever so briefly, so investors can buy and sell without any delay. “They’re selling the service of convenience to investors, like a car dealer makes it easier to buy or sell a car quickly,” said Jim Angel, an associate professor specializing in market structure at Georgetown University.

Knight Capital is a giant in the field; it alone was responsible for 11 percent of all trading in U.S. stocks by volume as of 2012. It’s known in particular for speed. The ability to jump in and out of stocks quickly through electronic markets is attractive to customers and enables Knight to trade nearly $30 billion every single day. “Market making is a business where the spreads are small but the volumes are large,” Angel said. The spread is the difference between the buy price and the sell price, and it’s how Knight makes money.

DiIorio looked closely at how Knight operated. He determined that between 80 and 90 percent of its share volumes came from penny and fractional penny stocks. According to DiIorio’s calculations, Knight traded over 10 trillion shares of OTC and Pink Sheets securities from 2004 to 2012.

This level of volume persists — the most recent statistics show that 73 percent of the company’s equity share volumes in August 2016 came from penny stocks, and 81 percent as recently as May.

A share in a penny stock is worth magnitudes less than a share in Google or Apple. But the spreads — where the market makers cash in — are proportionately bigger on a penny stock. For example, if the market maker earns a penny per share of a $50 stock, that’s only a spread of .02 percent. But a stock worth 25 cents where a market maker sees even a tenth of a penny in profit represents a spread of 2 percent — a 100-fold increase.

Still, DiIorio wondered how much volume a broker would need to make any money through penny stock trading. “You would have to move hundreds of millions of shares per trade,” he said.

And, because his personal investigation had started after his shares in a company called Best Rate Travel tanked precipitously, he also wondered: Why was Knight so involved with them in particular?

While DiIorio was mulling that, he started talking to his fellow traders and reading rumors online from owners of dozens of small companies who blamed the rapid destruction of their penny stocks on a practice known as naked short selling.

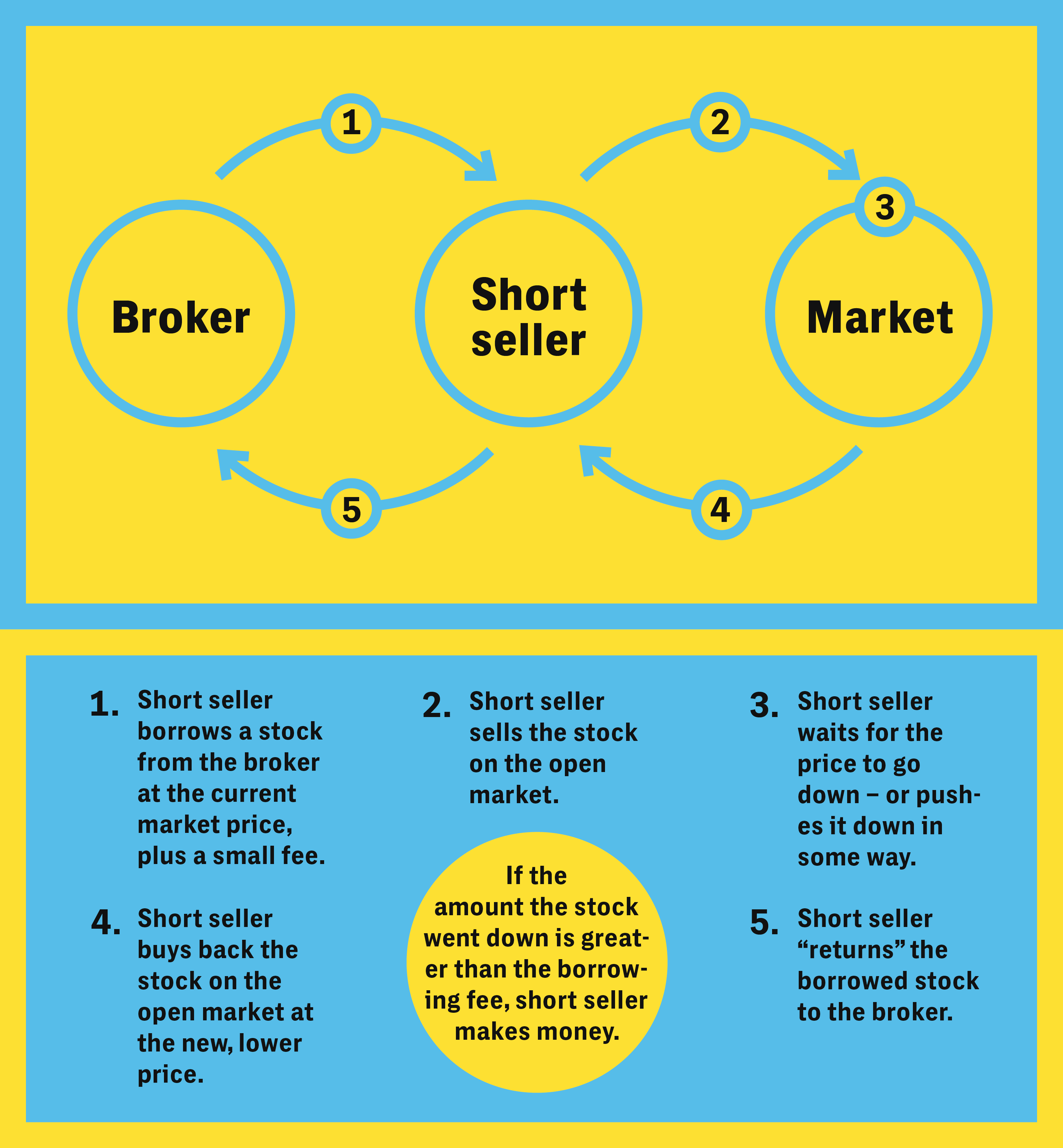

Let’s take that step by step. A short sale, generally speaking, is a bet that a stock price will drop over time. Typically, short sellers borrow shares of a stock from a broker and sell them on the open market, hoping to buy them back at a cheaper price in the future and make money on the exchange. This can become a self-fulfilling prophecy, if done right. Short selling can cause a market panic, and the prices drop in the frenzy.

How to short a stock.

Graphic: The Intercept.

But in naked short selling, you don’t even borrow the stock. You sell additional, phantom shares. This is even more likely to drive down the price than regular shorting, because suddenly the supply is larger but the demand is the same. “I can think of a number of stocks where the shares on the short exceeded the shares ever issued by the company,” said Alabama Securities Commission Director Joseph Borg. “You can’t do that unless it’s naked.”

Naked short selling is, not surprisingly, illegal in most circumstances.

But market makers like Knight have an exemption from naked short selling restrictions, on the grounds that they use the practice to maintain liquidity in markets. For example, if there’s high demand for a stock, the market maker can fill orders even if it doesn’t have the shares available.

As the Securities and Exchange Commission explains, “A market maker engaged in bona fide market making, particularly in a fast-moving market, may need to sell the security short without having arranged to borrow shares.” This often occurs in thinly traded stocks, like penny stocks.

DiIorio reasoned that naked short selling would explain where all the trades were coming from on Best Rate Travel; while he and his counterparts were locked into their investments for a year after the company’s merger, maybe someone was flooding the market with shares and battering the stock with ease.

At this point, DiIorio had no evidence that Knight did anything but facilitate trades. But he began to suspect that Knight somehow used naked short selling for its own devices. DiIorio’s attempts to get some explanations from Knight were brushed off — as were The Intercept’s during the reporting of this series.

Did Knight manipulate the stock price of Best Rate Travel, costing DiIorio and other investors millions? If so, why? Who benefited? Who needed this obscure, tiny penny stock to tank?

Knight earned $333 million in pre-tax profits in 2008, and another $232 million in 2009. But DiIorio didn’t think Knight was making that kind of money simply from executing transactions for clients.

As a market maker, Knight was in the rare position of being able to legally sell a stock it didn’t have (the principle being that it will get that stock soon, so no worries). That’s called naked shorting. It’s illegal when regular people do it.

DiIorio suspected that Knight, either on its own behalf or on behalf of clients, made a practice of artificially increasing the number of shares available in a stock through naked shorting, thereby depressing the price.

His suspicion grew when he noticed that Knight often traded in securities that were red-flagged on the Depository Trust Company’s “chill list.”

The DTC is an obscure financial industry-owned company that manages the custody of more than $1 quadrillion in securities annually, recording the transfers with journal entries and guaranteeing the trade. The company makes it easy for people to buy and sell securities without needing to exchange paper stock.

But when the DTC senses trouble, it will stop clearing trades on a stock temporarily.

A chilled stock can still trade — as long as the market participants handle the physical certificates themselves. But it can be a sign that something is gravely wrong. The DTC states on its website that it chills stocks “when there are questions about an issuer’s compliance with applicable law.”

That doesn’t stop Knight from buying and selling them, though. Its chief legal officer, Thomas Merritt, acknowledged at a 2011 Securities and Exchange Commission roundtable that the company actively traded chilled stocks, saying that as long as the security still trades, “we are going to be involved in that business.” And DiIorio found numerous examples of Knight trading chilled penny stocks.

“I didn’t know they did that,” said Jim Angel, a Georgetown University business school professor. “I’m kind of shocked to think that Knight would be working with paper stock certificates.”

He suggested that Knight might simply want to accommodate customers trying to get out of chilled stocks. “Or maybe they feel there’s enough interest in a security that they can trade profitably, even if they have to shuffle the certificates.”

Because most other market makers flee chilled stocks, however, this means Knight can assume even more control over the stock price.

Naked Manipulation

The thing about naked short sales is they can’t stay naked forever.

Even if you don’t have the stock when you sell it, at some point it is expected that you hand it over.

And even with its market-maker exemption, Knight is required by SEC rules to eventually deliver the shares in a naked short transaction to the buyer and close out the trade.

Not doing so results in a “fail to deliver,” which DiIorio describes as the securities version of an IOU. And that IOU comes with rules: Under the SEC’s Regulation SHO, short sellers have to cough up the stock within one day of incurring the fail. Routine failures to deliver can lead to fines by the SEC, or even a ban from the securities markets.

Instead of complying with the rule, however, DiIorio alleges that Knight circumvented it by manipulating an obscure process within the machinery of the nation’s clearing system known as the “Obligation Warehouse.”

This service facilitates the matching of self-cleared trades (often known as “ex-clearing”) that don’t go through the DTC — for instance if the stock was chilled.

The Obligation Warehouse instead simply asks the buyer and seller of these ex-cleared trades if they “know” the transaction. If they both agree, the trade gets confirmed with a journal entry — and the buyer receives their stock purchase. It actually shows up in the buyer’s brokerage account.

The trades still have active IOUs, but according to DiIorio’s theory, buyers wouldn’t clamor for the trades to be closed because they would’ve already received their purchase.

If true, this would allow Knight to bury its naked short trades.

“They set up a shadow clearing system,” DiIorio said.

Furthermore, DiIorio recognized what he considered a persistent cycle in the stocks Knight traded. After being beaten down through what he suspected was naked shorting, they would often engage in a reverse stock split or reverse merger, like E Mobile did with Best Rate Travel in the trade that ended up losing DiIorio over $1 million.

This, he observed, could enable Knight to rerun the scheme over and over again, pummeling the stock price and then letting it move back up like a yo-yo.

Laura Posner of the New Jersey Securities Commission said constant reverse splits would require a coordinated relationship between the penny stock issuer and the broker-dealer. “I know that there are situations in which fraudsters will take advantage of a stock split to commit fraud,” Posner said. “But it’s different than a typical pump-and-dump, where you don’t have to have a personal relationship.”

Alternately, the cycle could be a cat-and-mouse game playing out between the short sellers and the stock issuers. Hawk Associates, a consulting firm to small companies, recommends that penny stock issuers victimized by naked shorting engage in reverse mergers and/or reverse splits to stop the rapid degradation of their stock price. “It may be useful as part of a larger strategy to deter naked shorting,” the firm writes on its website. “This may be more trouble than it’s worth, however. Once the new shares are in circulation, there’s nothing to stop a new round of naked shorting by determined parties.”

Knight’s involvement with suspicious stocks following this same pattern kept cropping up.

For example, NewLead Holdings (NEWL) — a shipping company with a mining concern on the side that was accused in federal court of having “no coal mines, no coal, and no ability whatsoever to engage in the coal business” — engaged in 1-1,125,000 worth of reverse splits over nine months in 2013 and 2014, meaning that 1,000 shares prior to the splits were equivalent to 0.0008 shares afterward. NewLead did another 1-300 stock split just this spring; it now trades as NEWLF, at 0.00030 as of August 23. Its 2015 annual report admits, “There is substantial doubt about our ability to continue as a going concern.”

FreeSeas (FREE), another penny stock, did a 1-60 reverse split on January 15 of this year, and then another 1-200 split on April 13, changing its stock symbol to FREEF. The company has engaged in seven reverse splits in the last five years; someone with 900 million shares five years ago would have one share today, trading at less than a penny. The company’s annual report says it currently has no employees. Private equity firm Havensight Capital made an alleged bid to purchase FreeSeas in June at $0.43 a share, about 80 times its price at the time of this writing, which FreeSeas called “false and misleading.”

While one might think this cycle of splits and price declines would trigger red flags with federal regulators, Joseph Borg of the Alabama Securities Commission doubted they would pay attention. “It’s like asking the SEC, of all the 35,000 private placements issued, you look at how many? And if they were telling the truth they would say we’re putting them in a drawer,” Borg said. “Anything like that on miniscule levels, they just get filed away.”

Furthermore, while there are “circuit breaker” rules preventing short sales when a stock loses more than 10 percent of its value in a day, these swings were more gradual. Knight made a lot of money on these plays, not just from the spread in trading profits, but because it often traded on its own account rather than on behalf of customers, DiIorio concluded. When the stock dropped, Knight got rich from the short. And it could rerun this repeatedly

“He’s got a theory that, without studying it, I see theoretically where he’s going with it,” concluded Borg. “It’s an interesting idea.”

Knight is now known as KCG. Its spokesperson Sophie Sohn declined to comment when asked about this and other matters.

Attempts to reach spokespeople at FreeSeas have proven unsuccessful. Elisa Gerouki, corporate communications manager at NewLead, asked me to prove he wrote for The Intercept; after I did so, Gerouki failed to respond to questions.

Where Naked Shorts Go to Die

DiIorio also spotted a significant, seemingly toxic byproduct of this sort of activity.

Graphic: The Intercept.

Reverse mergers and reverse splits typically result in a change in the CUSIP, the nine-digit identification symbol assigned to a public stock.

Once that CUSIP changes, the naked shorter has no apparent way to close out the naked short position. No stock under the old CUSIP number exists anymore; it all automatically converts to the new CUSIP.

Those trades can sit in the Obligation Warehouse forever, in theory. But the “aged fails” — essentially orphaned naked short transactions — remain on the naked shorter’s balance sheet as a liability to be paid later.

By DiIorio’s reckoning, then, the cycle of naked shorting and reverse splits would inevitably result in an ever-increasing number of aged fails. And if that was happening, and those liabilities grew bigger and bigger, then federal regulators could see the outlines of the scheme on any financial statement.

DiIorio believed Knight accounted for its aged fails in the “sold not yet purchased” liability on its balance sheet. That’s supposed to be an inventory of stocks for use in future market making, which goes up and down as orders are filled. But DiIorio says it was a hiding place for a billowing structural liability.

And consider this: According to its own financial reports, Knight’s “sold not yet purchased” liability jumped from $385 million at the beginning of 2008 to $1.9 billion by mid-2011.

Jim Angel, the business professor, said there could be other explanations — such as Knight’s growth as a company during that period — for why the “sold not yet purchased” liability ballooned. But, he said, market makers are typically “in the moving, not storing, business, and like to keep their inventories as small as possible.”

DiIorio had no such doubts. He saw the fact that Knight was blowing a hole in its own balance sheet as undeniable evidence of the naked shorting play.

KCG spokesperson Sophie Sohn was asked specifically about that claim and declined to comment.

If DiIorio was correct, Knight was driving penny stocks down over and over again with naked shorting, then not actually closing the trades, and racking up enormous paper liabilities.

This was even more complicated than he thought. It was time to call the cops.

It had taken him five years to reach these conclusions — five years of digging through reams of financial data in search of answers to how and why his particular penny stock investment was so brutally crushed. Knight never answered DiIorio’s questions, nor, during the reporting of this story, any of The Intercept’s.

In April 2011, DiIorio decided he had to alert the Securities and Exchange Commission. He reached out to the SEC through its Office of the Whistleblower.

“The core business at Knight has always been naked shorting penny stocks,” DiIorio asserted.

Shorting a stock is betting it will drop in price: You borrow a share, sell it, hope the stock price drops, then buy another share to pay back your loan, hopefully for less than you borrowed it for.

In naked shorting, you sell a share that doesn’t exist and cash the proceeds. Do that enough and you bet the price will drop. Set it up so that it looks like you really sold the share to everyone except an obscure middleman, and the only toxic byproduct is a liability on your balance sheet representing shares you have sold but not yet purchased.

DiIorio believed this represented the secret of Knight’s success. “I told the SEC, ‘If you don’t believe me, ask Knight!’ If their penny stock volumes went to zero, what would happen to their trading profits?”

DiIorio filed a TCR (tip, complaint, or referral) form. Under Section 922 of the Dodd-Frank Act, the SEC has the authority to provide substantial monetary awards to eligible whistleblowers who inform the agency of securities law violations, if the subsequent enforcement actions exceed $1 million. But DiIorio says he wasn’t trying to win back his losses by filing a whistleblower complaint; he just wanted to see the ongoing fraud of investors like him put to a stop.

He also pointed to the threat to the markets from Knight’s thinning capital compared to the billion-dollar-plus “sold not yet purchased” liability. “I said, ‘Knight is insolvent, and this is how I know.’”

Indeed, the firm’s own second-quarter 2011 report to the SEC clearly showed $1.9 billion in “sold, not yet purchased” liabilities — up from $1.3 billion just six months earlier. By contrast, it reported “net current assets, which consist of net assets readily convertible into cash less current liabilities, of $105.1 million.”

Other than a perfunctory acknowledgement of receipt, the SEC did not respond to the TCR. DiIorio sent personal emails to top officials at the agency. One still exists on the SEC’s website, an October 2011 letter to Robert Khuzami, then the SEC’s head of enforcement. “Why won’t [then-Knight CEO Thomas] Joyce disclose to the investing public the nearly [$2 billion] sold not yet purchased liability is where he moves aged fails,” DiIorio wrote. “It is a structural liability and does not in fact ‘fluctuate with volumes’ as [Joyce] has said in several public filings.”

In this case, aged fails are the obligation left over when the stock whose shares the seller was supposed to actually hand over no longer exists because of a merger or split.

SEC spokesperson Ryan White declined to comment on the matter. As a matter of policy, the SEC never confirms nor denies the existence of an investigation until it reaches the public record in a court action or administrative proceeding, and it usually doesn’t inform whistleblowers about the status of their cases unless it grants them an enforcement award.

But DiIorio grew frustrated with the lack of response. “I was baffled why the SEC was not acting on what appeared to be blatant securities violations,” he said.

What About UBS?

He used the delay, however, to clear up another nagging question: What about the other major trader in these penny stocks, the Swiss bank UBS, one of the largest private banks in the world?

Time after time, DiIorio would isolate individual penny stocks and find UBS and Knight as major traders in them. While it wasn’t possible to know for sure, the correlation suggested that UBS was repeatedly on the other side of Knight’s trades; its clients would go long while Knight’s would go short. If true, that meant UBS, or its clients, were taking on multitudes of losses by design.

Why was UBS so involved with penny stocks, which had little upside potential for a global megabank? Why was it so intertwined with Knight? Who was it purchasing these penny stocks for?

And why didn’t the bank seem to care that its clients were being sold stock that kept going down in value?

Hinterlasse einen Kommentar

An der Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlasse uns deinen Kommentar!