Ich habe ja bereits vor einigen Tagen über das Ethereum IPO berichtet. Jetzt zeigen sich leider schon erste Probleme. Für das Entwicklerteam um „Wunderkind“ Vitalik Buterin gab es einen herben Rückschlag, als ein …

ethereum – Google Blogsuche

Special thanks to Andrew Miller for coming up with this attack, and to Zack Hess, Vlad Zamfir and Paul Sztorc for discussion and responses

One of the more interesting surprises in cryptoeconomics in recent weeks came from an attack on SchellingCoin conceived by Andrew Miller earlier this month. Although it has always been understood that SchellingCoin, and similar systems (including the more advanced Truthcoin consensus), rely on what is so far a new and untested cryptoeconomic security assumption – that one can safely rely on people acting honestly in a simultaneous consensus game just because they believe that everyone else will – the problems that have been raised so far have to do with relatively marginal issues like an attacker’s ability to exert small but increasing amounts of influence on the output over time by applying continued pressure. This attack, on the other hand, shows a much more fundamental problem.

The scenario is described as follows. Suppose that there exists a simple Schelling game where users vote on whether or not some particular fact is true (1) or false (0); say in our example that it’s actually false. Each user can either vote 1 or 0. If a user votes the same as the majority, they get a reward of P; otherwise they get 0. Thus, the payoff matrix looks as follows:

| You vote 0 | You vote 1 | |

| Others vote 0 | P | 0 |

| Others vote 1 | 0 | P |

The theory is that if everyone expects everyone else to vote truthfully, then their incentive is to also vote truthfully in order to comply with the majority, and that’s the reason why one can expect others to vote truthfully in the first place; a self-reinforcing Nash equilibrium.

Now, the attack. Suppose that the attacker credibly commits (eg. via an Ethereum contract, by simply putting one’s reputation at stake, or by leveraging the reputation of a trusted escrow provider) to pay out X to voters who voted 1 after the game is over, where X = P + ε if the majority votes 0, and X = 0 if the majority votes 1. Now, the payoff matrix looks like this:

| You vote 0 | You vote 1 | |

| Others vote 0 | P | P + ε |

| Others vote 1 | 0 | P |

Thus, it’s a dominant strategy for anyone to vote 1 no matter what you think the majority will do. Hence, assuming the system is not dominated by altruists, the majority will vote 1, and so the attacker will not need to pay anything at all. The attack has successfully managed to take over the mechanism at zero cost. Note that this differs from Nicholas Houy’s argument about zero-cost 51% attacks on proof of stake (an argument technically extensible to ASIC-based proof of work) in that here no epistemic takeover is required; even if everyone remains dead set in a conviction that the attacker is going to fail, their incentive is still to vote to support the attacker, because the attacker takes on the failure risk themselves.

Salvaging Schelling Schemes

There are a few avenues that one can take to try to salvage the Schelling mechanism. One approach is that instead of round N of the Schelling consensus itself deciding who gets rewarded based on the “majority is right” principle, we use round N + 1 to determine who should be rewarded during round N, with the default equilibrium being that only people who voted correctly during round N (both on the actual fact in question and on who should be rewarded in round N – 1) should be rewarded. Theoretically, this requires an attacker wishing to perform a cost-free attack to corrupt not just one round, but also all future rounds, making the required capital deposit that the attacker must make unbounded.

However, this approach has two flaws. First, the mechanism is fragile: if the attacker manages to corrupt some round in the far future by actually paying up P + ε to everyone, regardless of who wins, then the expectation of that corrupted round causes an incentive to cooperate with the attacker to back-propagate to all previous rounds. Hence, corrupting one round is costly, but corrupting thousands of rounds is not much more costly.

Second, because of discounting, the required deposit to overcome the scheme does not need to be infinite; it just needs to be very very large (ie. inversely proportional to the prevailing interest rate). But if all we want is to make the minimum required bribe larger, then there exists a much simpler and better strategy for doing so, pioneered by Paul Storcz: require participants to put down a large deposit, and build in a mechanism by which the more contention there is, the more funds are at stake. At the limit, where slightly over 50% of votes are in favor of one outcome and 50% in favor of the other, the entire deposit it taken away from minority voters. This ensures that the attack still works, but the bribe must now be greater than the deposit (roughly equal to the payout divided by the discounting rate, giving us equal performance to the infinite-round game) rather than just the payout for each round. Hence, in order to overcome such a mechanism, one would need to be able to prove that one is capable of pulling off a 51% attack, and perhaps we may simply be comfortable with assuming that attackers of that size do not exist.

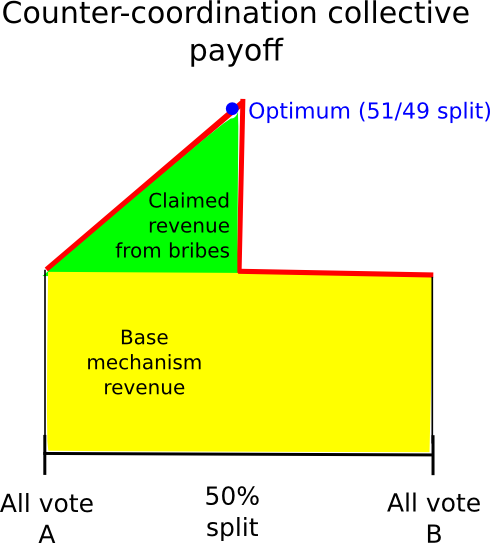

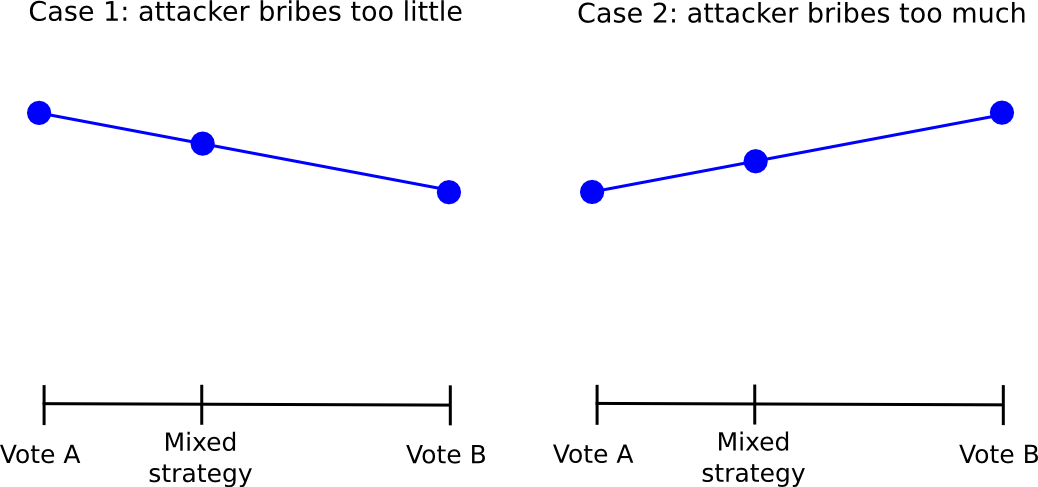

Another approach is to rely on counter-coordination; essentially, somehow coordinate, perhaps via credible commitments, on voting A (if A is the truth) with probability 0.6 and B with probability 0.4, the theory being that this will allow users to (probabilistically) claim the mechanism’s reward and a portion of the attacker’s bribe at the same time. This (seems to) work particularly well in games where instead of paying out a constant reward to each majority-compliant voter, the game is structured to have a constant total payoff, adjusting individual payoffs to accomplish this goal is needed. In such situations, from a collective-rationality standpoint it is indeed the case that the group earns a highest profit by having 49% of its members vote B to claim the attacker’s reward and 51% vote A to make sure the attacker’s reward is paid out.

However, this approach itself suffers from the flaw that, if the attacker’s bribe is high enough, even from there one can defect. The fundamental problem is that given a probabilistic mixed strategy between A and B, for each the return always changes (almost) linearly with the probability parameter. Hence, if, for the individual, it makes more sense to vote for B than for A, it will also make more sense to vote with probability 0.51 for B than with probability 0.49 for B, and voting with probability 1 for B will work even better.

Hence, everyone will defect from the “49% for 1″ strategy by simply always voting for 1, and so 1 will win and the attacker will have succeeded in the costless takeover. The fact that such complicated schemes exist, and come so close to “seeming to work” suggests that perhaps in the near future some complex counter-coordination scheme will emerge that actually does work; however, we must be prepared for the eventuality that no such scheme will be developed.

Further Consequences

Given the sheer number of cryptoeconomic mechanisms that SchellingCoin makes possible, and the importance of such schemes in nearly all purely “trust-free” attempts to forge any kind of link between the cryptographic world and the real world, this attack poses a potential serious threat – although, as we will later see, Schelling schemes as a category are ultimately partially salvageable. However, what is more interesting is the much larger class of mechanisms that don’t look quite like SchellingCoin at first glance, but in fact have very similar sets of strengths and weaknesses.

Particularly, let us point to one very specific example: proof of work. Proof of work is in fact a multi-equilibrium game in much the same way that Schelling schemes are: if there exist two forks, A and B, then if you mine on the fork that ends up winning you get 25 BTC and if you mine on the fork that ends up losing you get nothing.

| You mine on A | You mine on B | |

| Others mine on A | 25 | 0 |

| Others mine on B | 0 | 25 |

Now, suppose that an attacker launches a double-spend attack against many parties simultaneously (this requirement ensures that there is no single party with very strong incentive to oppose the attacker, opposition instead becoming a public good; alternatively the double spend could be purely an attempt to crash the price with the attacker shorting at 10x leverage), and call the “main” chain A and the attacker’s new double-spend fork B. By default, everyone expects A to win. However, the attacker credibly commits to paying out 25.01 BTC to everyone who mines on B if B ends up losing. Hence, the payoff matrix becomes:

| You mine on A | You mine on B | |

| Others mine on A | 25 | 25.01 |

| Others mine on B | 0 | 25 |

Thus, mining on B is a dominant strategy regardless of one’s epistemic beliefs, and so everyone mines on B, and so the attacker wins and pays out nothing at all. Particularly, note that in proof of work we do not have deposits, so the level of bribe required is proportional only to the mining reward multiplied by the fork length, not the capital cost of 51% of all mining equipment. Hence, from a cryptoeconomic security standpoint, one can in some sense say that proof of work has virtually no cryptoeconomic security margin at all (if you are tired of opponents of proof of stake pointing you to this article by Andrew Poelstra, feel free to link them here in response). If one is genuinely uncomfortable with the weak subjectivity condition of pure proof of stake, then it follows that the correct solution may perhaps be to augment proof of work with hybrid proof of stake by adding security deposits and double-voting-penalties to mining.

Of course, in practice, proof of work has survived despite this flaw, and indeed it may continue to survive for a long time still; it may just be the case that there’s a high enough degree of altruism that attackers are not actually 100% convinced that they will succeed – but then, if we are allowed to rely on altruism, naive proof of stake works fine too. Hence, Schelling schemes too may well simply end up working in practice, even if they are not perfectly sound in theory.

The next part of this post will discuss the concept of “subjective” mechanisms in more detail, and how they can be used to theoretically get around some of these problems.

The post The P + epsilon Attack appeared first on .

The Federal Reserve Bank has released its highly anticipated strategy report for improving the U.S. payment system.

The report follows calls for industry feedback in late 2013—which Ripple Labs participated in (letter, response)—during which the Federal Reserve acknowledged the payment system’s contribution to not only the country’s financial stability but also U.S. economic growth. The need to improve the nation’s underlying infrastructure had reached a critical juncture, the Fed concluded.

To put the significance of the Fed’s strategy report into context, this is the central bank’s first major initiative to upgrade the domestic payment system since the creation of ACH in the 1970s. This is a big deal—and the goal is clear.

The report’s executive summary overviews the current situation:

The Federal Reserve believes that the U.S. payment system is at a critical juncture in its evolution. Technology is rapidly changing many elements that support the payment process. High-speed data networks are becoming ubiquitous, computing devices are becoming more sophisticated and mobile, and information is increasingly processed in real time. These capabilities are changing the nature of commerce and end-user expectations for payment services.

Meanwhile, payment security and the protection of sensitive data, which are foundational to public confidence in any payment system, are challenged by dynamic, persistent and rapidly escalating threats. Finally, an increasing number of U.S. citizens and businesses routinely transfer value across borders and demand better payment options to swiftly and efficiently do so.

It’s also a call to arms:

Responses to the Federal Reserve’s 2013 Payment System Improvement – Public Consultation Paper (Consultation Paper) indicate broad agreement with the gaps, opportunities and desired outcomes discussed in that paper. Recent stakeholder dialogue has advanced significantly, and momentum toward common goals has increased.

Many payment stakeholders are now independently initiating actions to discuss payment system improvements with one another—especially the prospect of increasing end-to-end payment speed and security. We believe these developments illustrate a rare confluence of factors that create favorable conditions for change. Through this Strategies for Improving the U.S. Payment System paper, the Federal Reserve is calling on all stakeholders to seize this opportunity and join together to improve the payment system.

Of particular note are the potential solutions outlined by the report. Of the four solutions suggested, Ripple is the enabling technology described in option two (page 40). Ripple provides neutral payment infrastructure, and its users (banks, networks) set their own rules and governance in accordance with regulations set in their jurisdictions (e.g. the Fed in the U.S.).

Option 2: Facilitate direct clearing between financial institutions on public IP networks using protocols and standards for sending and receiving payments.

A distributed architecture for messaging between financial institutions over public IP networks has the potential to lower costs compared to clearing transactions over a hub-and-spoke network architecture. A central authority would establish common protocols for messaging standards, communication, security and logging transactions.

The Fed also made a statement about the design options it decided to exclude from further consideration, which included all proposals to evolve existing infrastructure such as ACH, wire transfers, and checks. They also decided to forego leveraging telecom infrastructure, a popular route in developing economies following the phenomenal success of M-Pesa.

The other options either involve leveraging the existing ATM/PIN debit infrastructure—which present numerous operational challenges such as “the high variability on implementation feasibility” and issue of “silos that often exist between the retail and commercial units of financial institutions”—or building new infrastructure from the ground up, which, while theoretically ideal as “a potential longer-term objective,” involves “potentially high cost.”

The Fed highlighted one of the primary weaknesses of the current status quo—that standards and protocols had failed to catch up to evolving needs as disparate networks and industry members failed to consistently reach consensus on new rulesets. The Fed pledged its commitment toward further industry coordination and cooperation to address this issue—which in our view underlines the unique advantage and responsibility of the central bank.

- See also: What the Fed Wants the Fed Can’t Have

That’s also why we see Ripple technology as such a compelling solution within the components defined by the Fed that compose a payment system—technology, rules, risk management, and the messaging standard. As an efficient, inexpensive, ruleset-agnostic solution, Ripple provides the technological layer while the Fed and other industry members can play to their strengths and provide complementary components such as rulesets.

Ripple Labs designed the Ripple protocol as such because we believe that local jurisdictions are best suited to define their own standards in connecting fragmented payment networks given the complexity of financial regulation. By applying jurisdiction-specific rulesets on top of a common technical infrastructure like Ripple, the various national payment systems around the world would benefit from increased interoperability and a significant improvement in the speed and cost of cross border payments.

Having analyzed the Fed’s consultation papers over the past two years, we believe Ripple comprehensively achieves many of the desired outcomes outlined by the Fed (page 8-15) along with addressing many of the existing weaknesses highlighted (page 34).

In general, we applaud the Fed’s ongoing initiative to provide a safe, efficient, and broadly accessible payment network. Their active and inclusive approach provides us further confidence in the work we are doing at Ripple Labs.

Follow Ripple on Twitter

Warning: this post contains crazy ideas. Myself describing a crazy idea should NOT be construed as implying that (i) I am certain that the idea is correct/viable, (ii) I have an even >50% probability estimate that the idea is correct/viable, or that (iii) “Ethereum” endorses any of this in any way.

One of the common questions that many in the crypto 2.0 space have about the concept of decentralized autonomous organizations is a simple one: what are DAOs good for? What fundamental advantage would an organization have from its management and operations being tied down to hard code on a public blockchain, that could not be had by going the more traditional route? What advantages do blockchain contracts offer over plain old shareholder agreements? Particularly, even if public-good rationales in favor of transparent governance, and guarnateed-not-to-be-evil governance, can be raised, what is the incentive for an individual organization to voluntarily weaken itself by opening up its innermost source code, where its competitors can see every single action that it takes or even plans to take while themselves operating behind closed doors?

There are many paths that one could take to answering this question. For the specific case of non-profit organizations that are already explicitly dedicating themselves to charitable causes, one can rightfully say that the lack of individual incentive; they are already dedicating themselves to improving the world for little or no monetary gain to themselves. For private companies, one can make the information-theoretic argument that a governance algorithm will work better if, all else being equal, everyone can participate and introduce their own information and intelligence into the calculation – a rather reasonable hypothesis given the established result from machine learning that much larger performance gains can be made by increasing the data size than by tweaking the algorithm. In this article, however, we will take a different and more specific route.

What is Superrationality?

In game theory and economics, it is a very widely understood result that there exist many classes of situations in which a set of individuals have the opportunity to act in one of two ways, either “cooperating” with or “defecting” against each other, such that everyone would be better off if everyone cooperated, but regardless of what others do each indvidual would be better off by themselves defecting. As a result, the story goes, everyone ends up defecting, and so people’s individual rationality leads to the worst possible collective result. The most common example of this is the celebrated Prisoner’s Dilemma game.

Since many readers have likely already seen the Prisoner’s Dilemma, I will spice things up by giving Eliezer Yudkowsky’s rather deranged version of the game:

However, substance S can only be produced by working with [a strange AI from another dimension whose only goal is to maximize the quantity of paperclips] – substance S can also be used to produce paperclips. The paperclip maximizer only cares about the number of paperclips in its own universe, not in ours, so we can’t offer to produce or threaten to destroy paperclips here. We have never interacted with the paperclip maximizer before, and will never interact with it again.

Both humanity and the paperclip maximizer will get a single chance to seize some additional part of substance S for themselves, just before the dimensional nexus collapses; but the seizure process destroys some of substance S.

The payoff matrix is as follows:

| Humans cooperate | Humans defect | |

| AI cooperates | 2 billion lives saved, 2 paperclips gained | 3 billion lives, 0 paperclips |

| AI defects | 0 lives, 3 paperclips | 1 billion lives, 1 paperclip |

From our point of view, it obviously makes sense from a practical, and in this case moral, standpoint that we should defect; there is no way that a paperclip in another universe can be worth a billion lives. From the AI’s point of view, defecting always leads to one extra paperclip, and its code assigns a value to human life of exactly zero; hence, it will defect. However, the outcome that this leads to is clearly worse for both parties than if the humans and AI both cooperated – but then, if the AI was going to cooperate, we could save even more lives by defecting ourselves, and likewise for the AI if we were to cooperate.

In the real world, many two-party prisoner’s dilemmas on the small scale are resolved through the mechanism of trade and the ability of a legal system to enforce contracts and laws; in this case, if there existed a god who has absolute power over both universes but cared only about compliance with one’s prior agreements, the humans and the AI could sign a contract to cooperate and ask the god to simultaneously prevent both from defecting. When there is no ability to pre-contract, laws penalize unilateral defection. However, there are still many situations, particularly when many parties are involved, where opportunities for defection exist:

- Alice is selling lemons in a market, but she knows that her current batch is low quality and once customers try to use them they will immediately have to throw them out. Should she sell them anyway? (Note that this is the sort of marketplace where there are so many sellers you can’t really keep track of reputation). Expected gain to Alice: $ 5 revenue per lemon minus $ 1 shipping/store costs = $ 4. Expected cost to society: $ 5 revenue minus $ 1 costs minus $ 5 wasted money from customer = -$ 1. Alice sells the lemons.

- Should Bob donate $ 1000 to Bitcoin development? Expected gain to society: $ 10 * 100000 people – $ 1000 = $ 999000, expected gain to Bob: $ 10 – $ 1000 = -$ 990, so Bob does not donate.

- Charlie found someone else’s wallet, containing $ 500. Should he return it? Expected gain to society: $ 500 (to recipient) – $ 500 (Charlie’s loss) + $ 50 (intangible gain to society from everyone being able to worry a little less about the safety of their wallets). Expected gain to Charlie: -$ 500, so he keeps the wallet.

- Should David cut costs in his factory by dumping toxic waste into a river? Expected gain to society: $ 1000 savings minus $ 10 average increased medical costs * 100000 people = -$ 999000, expected gain to David: $ 1000 – $ 10 = $ 990, so David pollutes.

- Eve developed a cure for a type of cancer which costs $ 500 per unit to produce. She can sell it for $ 1000, allowing 50,000 cancer patients to afford it, or for $ 10000, allowing 25,000 cancer patients to afford it. Should she sell at the higher price? Expected gain to society: -25,000 lives (including Alice’s profit, which cancels’ out the wealthier buyers’ losses). Expected gain to Eve: $ 237.5 million profit instead of $ 25 million = $ 212.5 million, so Eve charges the higher price.

Of course, in many of these cases, people sometimes act morally and cooperate, even though it reduces their personal situation. But why do they do this? We were produced by evolution, which is generally a rather selfish optimizer. There are many explanations. One, and the one we will focus on, involves the concept of superrationality.

Superrationality

Consider the following explanation of virtue, courtesy of David Friedman:

Suppose I wish people to believe that I have certain characteristics–that I am honest, kind, helpful to my friends. If I really do have those characteristics, projecting them is easy–I merely do and say what seems natural, without paying much attention to how I appear to outside observers. They will observe my words, my actions, my facial expressions, and draw reasonably accurate conclusions.

Suppose, however, that I do not have those characteristics. I am not (for example) honest. I usually act honestly because acting honestly is usually in my interest, but I am always willing to make an exception if I can gain by doing so. I must now, in many actual decisions, do a double calculation. First, I must decide how to act–whether, for example, this is a good opportunity to steal and not be caught. Second, I must decide how I would be thinking and acting, what expressions would be going across my face, whether I would be feeling happy or sad, if I really were the person I am pretending to be.

If you require a computer to do twice as many calculations, it slows down. So does a human. Most of us are not very good liars.

If this argument is correct, it implies that I may be better off in narrowly material terms–have, for instance, a higher income–if I am really honest (and kind and …) than if I am only pretending to be, simply because real virtues are more convincing than pretend ones. It follows that, if I were a narrowly selfish individual, I might, for purely selfish reasons, want to make myself a better person–more virtuous in those ways that others value.

The final stage in the argument is to observe that we can be made better–by ourselves, by our parents, perhaps even by our genes. People can and do try to train themselves into good habits–including the habits of automatically telling the truth, not stealing, and being kind to their friends. With enough training, such habits become tastes–doing “bad” things makes one uncomfortable, even if nobody is watching, so one does not do them. After a while, one does not even have to decide not to do them. You might describe the process as synthesizing a conscience.

Essentially, it is cognitively hard to convincingly fake being virtuous while being greedy whenever you can get away with it, and so it makes more sense for you to actually be virtuous. Much ancient philosophy follows similar reasoning, seeing virtue as a cultivated habit; David Friedman simply did us the customary service of an economist and converted the intuition into more easily analyzable formalisms. Now, let us compress this formalism even further. In short, the key point here is that humans are leaky agents – with every second of our action, we essentially indirectly expose parts of our source code. If we are actually planning to be nice, we act one way, and if we are only pretending to be nice while actually intending to strike as soon as our friends are vulnerable, we act differently, and others can often notice.

This might seem like a disadvantage; however, it allows a kind of cooperation that was not possible with the simple game-theoretic agents described above. Suppose that two agents, A and B, each have the ability to “read” whether or not the other is “virtuous” to some degree of accuracy, and are playing a symmetric Prisoner’s Dilemma. In this case, the agents can adopt the following strategy, which we assume to be a virtuous strategy:

- Try to determine if the other party is virtuous.

- If the other party is virtuous, cooperate.

- If the other party is not virtuous, defect.

If two virtuous agents come into contact with each other, both will cooperate, and get a larger reward. If a virtuous agent comes into contact with a non-virtuous agent, the virtuous agent will defect. Hence, in all cases, the virtuous agent does at least as well as the non-virtuous agent, and often better. This is the essence of superrationality.

As contrived as this strategy seems, human cultures have some deeply ingrained mechanisms for implementing it, particularly relating to mistrusting agents who try hard to make themselves less readable – see the common adage that you should never trust someone who doesn’t drink. Of course, there is a class of individuals who can convincingly pretend to be friendly while actually planning to defect at every moment – these are called sociopaths, and they are perhaps the primary defect of this system when implemented by humans.

Centralized Manual Organizations…

This kind of superrational cooperation has been arguably an important bedrock of human cooperation for the last ten thousand years, allowing people to be honest to each other even in those cases where simple market incentives might instead drive defection. However, perhaps one of the main unfortunate byproducts of the modern birth of large centralized organizations is that they allow people to effectively cheat others’ ability to read their minds, making this kind of cooperation more difficult.

Most people in modern civilization have benefited quite handsomely, and have also indirectly financed, at least some instance of someone in some third world country dumping toxic waste into a river to build products more cheaply for them; however, we do not even realize that we are indirectly participating in such defection; corporations do the dirty work for us. The market is so powerful that it can arbitrage even our own morality, placing the most dirty and unsavory tasks in the hands of those individuals who are willing to absorb their conscience at lowest cost and effectively hiding it from everyone else. The corporations themselves are perfectly able to have a smiley face produced as their public image by their marketing departments, leaving it to a completely different department to sweet-talk potential customers. This second department may not even know that the department producing the product is any less virtuous and sweet than they are.

The internet has often been hailed as a solution to many of these organizational and political problems, and indeed it does do a great job of reducing information asymmetries and offering transparency. However, as far as the decreasing viability of superrational cooperation goes, it can also sometimes make things even worse. Online, we are much less “leaky” even as individuals, and so once again it is easier to appear virtuous while actually intending to cheat. This is part of the reason why scams online and in the cryptocurrency space are more common than offline, and is perhaps one of the primary arguments against moving all economic interaction to the internet a la cryptoanarchism (the other argument being that cryptoanarchism removes the ability to inflict unboundedly large punishments, weakening the strength of a large class of economic mechanisms).

A much greater degree of transparency, arguably, offers a solution. Individuals are moderately leaky, current centralized organizations are less leaky, but organizations where randomly information is constantly being released to the world left, right and center are even more leaky than individuals are. Imagine a world where if you start even thinking about how you will cheat your friend, business partner or spouse, there is a 1% chance that the left part of your hippocampus will rebel and send a full recording of your thoughts to your intended victim in exchange for a $ 7500 reward. That is what it “feels” like to be the management board of a leaky organization.

This is essentially a restatement of the founding ideology behind Wikileaks, and more recently an incentivized Wikileaks alternative, slur.io came out to push the envelope further. However, Wikileaks exists, and yet shadowy centralized organizations also continue to still exist and are in many cases still quite shadowy. Perhaps incentivization, coupled with prediction-like-mechanisms for people to profit from outing their employers’ misdeeds, is what will open the floodgates for greater transparency, but at the same time we can also take a different route: offer a way for organizations to make themselves voluntarily, and radically, leaky and superrational to an extent never seen before.

… and DAOs

Decentralized autonomous organizations, as a concept, are unique in that their governance algorithms are not just leaky, but actually completely public. That is, while with even transparent centralized organizations outsiders can get a rough idea of what the organization’s temperament is, with a DAO outsiders can actually see the organization’s entire source code. Now, they do not see the “source code” of the humans that are behind the DAO, but there are ways to write a DAO’s source code so that it is heavily biased toward a particular objective regardless of who its participants are. A futarchy maximizing the average human lifespan will act very differently from a futarchy maximizing the production of paperclips, even if the exact same people are running it. Hence, not only is it the case that the organization will make it obvious to everyone if they start to cheat, but rather it’s not even possible for the organization’s “mind” to cheat.

Now, what would superrational cooperation using DAOs look like? First, we would need to see some DAOs actually appear. There are a few use-cases where it seems not too far-fetched to expect them to succeed: gambling, stablecoins, decentralized file storage, one-ID-per-person data provision, SchellingCoin, etc. However, we can call these DAOs type I DAOs: they have some internal state, but little autonomous governance. They cannot ever do anything but perhaps adjust a few of their own parameters to maximize some utility metric via PID controllers, simulated annealing or other simple optimization algorithms. Hence, they are in a weak sense superrational, but they are also rather limited and stupid, and so they will often rely on being upgraded by an external process which is not superrational at all.

In order to go further, we need type II DAOs: DAOs with a governance algorithm capable of making theoretically arbitrary decisions. Futarchy, various forms of democracy, and various forms of subjective extra-protocol governance (ie. in case of substantial disagreement, DAO clones itself into multiple parts with one part for each proposed policy, and everyone chooses which version to interact with) are the only ones we are currently aware of, though other fundamental approaches and clever combinations of these will likely continue to appear. Once DAOs can make arbitrary decisions, then they will be able to not only engage in superrational commerce with their human customers, but also potentially with each other.

What kinds of market failures can superrational cooperation solve that plain old regular cooperation cannot? Public goods problems may unfortunately be outside the scope; none of the mechanisms described here solve the massively-multiparty incentivization problem. In this model, the reason why organizations make themselves decentralized/leaky is so that others will trust them more, and so organizations that fail to do this will be excluded from the economic benefits of this “circle of trust”. With public goods, the whole problem is that there is no way to exclude anyone from benefiting, so the strategy fails. However, anything related to information asymmetries falls squarely within the scope, and this scope is large indeed; as society becomes more and more complex, cheating will in many ways become progressively easier and easier to do and harder to police or even understand; the modern financial system is just one example. Perhaps the true promise of DAOs, if there is any promise at all, is precisely to help with this.

The post Superrationality and DAOs appeared first on .

Nearly 300 Ripple enthusiasts attended Around the World in 5 Seconds.

Despite pouring rain, nearly three hundred guests attended Around the World in 5 Seconds, a special night of demos and celebration at the Ripple Labs office in downtown San Francisco, an event meant to engage the local community and share our vision of Ripple’s potential.

Attendees ranged from engineers, product managers, and senior executives from blue-chip tech, banking and consulting companies to entrepreneurs bootstrapping their own ventures.

Signing in.

A series of product demos provided developers, investors, and industry leaders a tangible, hands-on experience for understanding how the Ripple protocol facilitates faster, cheaper, and more frictionless global payments than ever before.

Learning about the intricacies of real-time settlement and the internet-of-value.

One demo station was manned by Marco Montes, who you might recognize from the newly re-designed Ripple.com homepage. Marco is the founder and CEO of Saldo.mx, a novel remittance service that allows US customers to pay bills back in Mexico using the Ripple protocol.

Ripple Labs CTO Stefan Thomas and software engineer Evan Schwartz delivered two back-to-back tech talks on Codius, an ecosystem for developing distributed applications that utilizes smart contracts, to two jam-packed and enthusiastic crowds.

Stefan and Evan explain Codius.

The presentation represents the first of a series of talks as part of our mission to better educate the broader community about Ripple technology, behind the scenes developments, as well as our take on the industry at large.

A warm thank you to all those who weathered the storm and helped make this inaugural event a resounding success. It surely won’t be the last so we look forward to seeing you at the next one, along with those who weren’t able to make it out this time.

It was a packed house. See you next time!

Check out the Ripple Labs Facebook page for more photos of the event—courtesy of Ripple Labs senior software engineer and “head of photography,” Vahe Hovhannisyan. (You should also check out his Instagram.)

Follow Ripple on Twitter

Special thanks to Vlad Zamfir and Jae Kwon for many of the ideas described in this post

Aside from the primary debate around weak subjectivity, one of the important secondary arguments raised against proof of stake is the issue that proof of stake algorithms are much harder to make light-client friendly. Whereas proof of work algorithms involve the production of block headers which can be quickly verified, allowing a relatively small chain of headers to act as an implicit proof that the network considers a particular history to be valid, proof of stake is harder to fit into such a model. Because the validity of a block in proof of stake relies on stakeholder signatures, the validity depends on the ownership distribution of the currency in the particular block that was signed, and so it seems, at least at first glance, that in order to gain any assurances at all about the validity of a block, the entire block must be verified.

Given the sheer importance of light client protocols, particularly in light of the recent corporate interest in “internet of things” applications (which must often necessarily run on very weak and low-power hardware), light client friendliness is an important feature for a consensus algorithm to have, and so an effective proof of stake system must address it.

Light clients in Proof of Work

In general, the core motivation behind the “light client” concept is as follows. By themselves, blockchain protocols, with the requirement that every node must process every transaction in order to ensure security, are expensive, and once a protocol gets sufficiently popular the blockchain becomes so big that many users become not even able to bear that cost. The Bitcoin blockchain is currently 27 GB in size, and so very few users are willing to continue to run “full nodes” that process every transaction. On smartphones, and especially on embedded hardware, running a full node is outright impossible.

Hence, there needs to be some way in which a user with far less computing power to still get a secure assurance about various details of the blockchain state – what is the balance/state of a particular account, did a particular transaction process, did a particular event happen, etc. Ideally, it should be possible for a light client to do this in logarithmic time – that is, squaring the number of transactions (eg. going from 1000 tx/day to 1000000 tx/day) should only double a light client’s cost. Fortunately, as it turns out, it is quite possible to design a cryptocurrency protocol that can be securely evaluated by light clients at this level of efficiency.

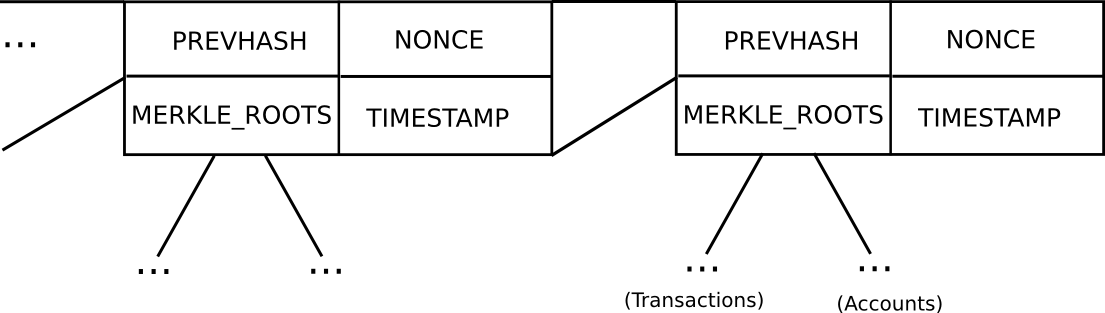

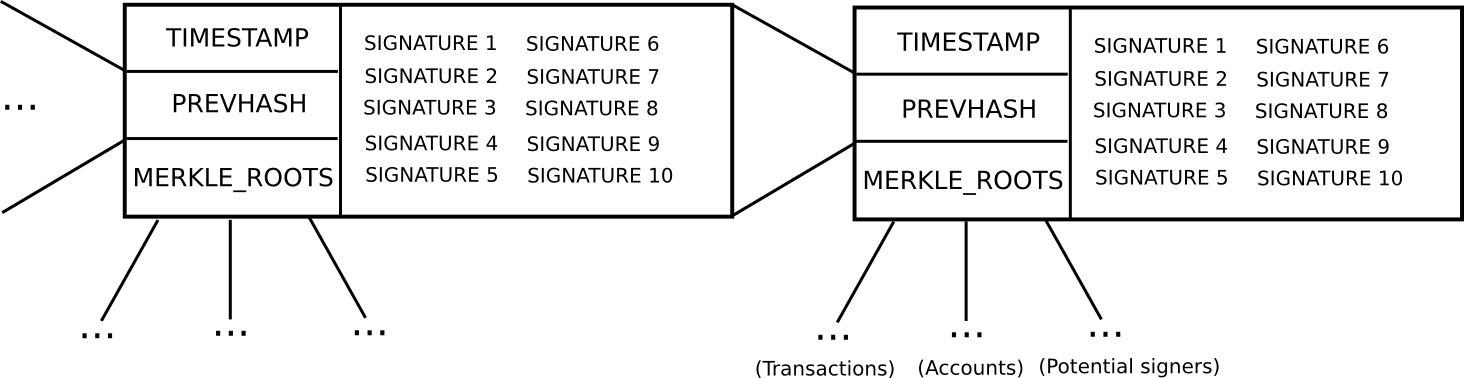

Basic block header model in Ethereum (note that Ethereum has a Merkle tree for transactions and accounts in each block, allowing light clients to easily access more data)

In Bitcoin, light client security works as follows. Instead of constructing a block as a monolithic object containing all of the transactions directly, a Bitcoin block is split up into two parts. First, there is a small piece of data called the block header, containing three key pieces of data:

- The hash of the previous block header

- The Merkle root of the transaction tree (see below)

- The proof of work nonce

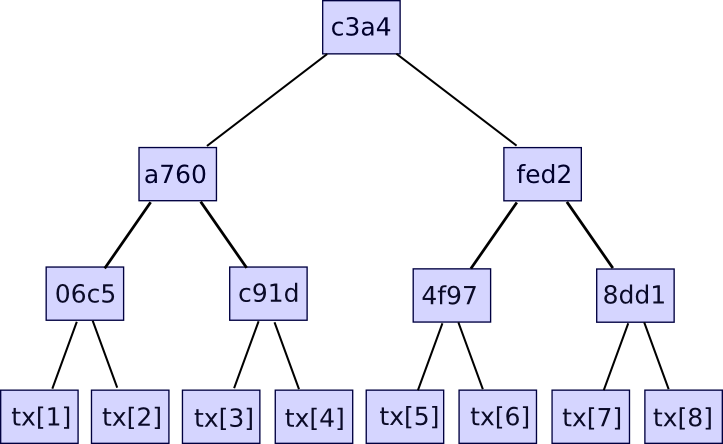

Additional data like the timestamp is also included in the block header, but this is not relevant here. Second, there is the transaction tree. Transactions in a Bitcoin block are stored in a data structure called a Merkle tree. The nodes on the bottom level of the tree are the transactions, and then going up from there every node is the hash of the two nodes below it. For example, if the bottom level had sixteen transactions, then the next level would have eight nodes: hash(tx[1] + tx[2]), hash(tx[3] + tx[4]), etc. The level above that would have four nodes (eg. the first node is equal to hash(hash(tx[1] + tx[2]) + hash(tx[3] + tx[4]))), the level above has two nodes, and then the level at the top has one node, the Merkle root of the entire tree.

The Merkle root can be thought of as a hash of all the transactions together, and has the same properties that you would expect out of a hash – if you change even one bit in one transaction, the Merkle root will end up completely different, and there is no way to come up with two different sets of transactions that have the same Merkle root. The reason why this more complicated tree construction needs to be used is that it actually allows you to come up with a compact proof that one particular transaction was included in a particular block. How? Essentially, just provide the branch of the tree going down to the transaction:

The verifier will verify only the hashes going down along the branch, and thereby be assured that the given transaction is legitimately a member of the tree that produced a particular Merkle root. If an attacker tries to change any hash anywhere going down the branch, the hashes will no longer match and the proof will be invalid. The size of each proof is equal to the depth of the tree – ie. logarithmic in the number of transactions. If your block contains 220 (ie. ~1 million) transactions, then the Merkle tree will have only 20 levels, and so the verifier will only need to compute 20 hashes in order to verify a proof. If your block contains 230 (ie. ~1 billion) transactions, then the Merkle tree will have 30 levels, and so a light client will be able to verify a transaction with just 30 hashes.

Ethereum extends this basic mechanism with a two additional Merkle trees in each block header, allowing nodes to prove not just that a particular transaction occurred, but also that a particular account has a particular balance and state, that a particular event occurred, and even that a particular account does not exist.

Verifying the Roots

Now, this transaction verification process all assumes one thing: that the Merkle root is trusted. If someone proves to you that a transaction is part of a Merkle tree that has some root, that by itself means nothing; membership in a Merkle tree only proves that a transaction is valid if the Merkle root is itself known to be valid. Hence, the other critical part of a light client protocol is figuring out exactly how to validate the Merkle roots – or, more generally, how to validate the block headers.

First of all, let us determine exactly what we mean by “validating block headers”. Light clients are not capable of fully validating a block by themselves; protocols exist for doing validation collaboratively, but this mechanism is expensive, and so in order to prevent attackers from wasting everyone’s time by throwing around invalid blocks we need a way of first quickly determining whether or not a particular block header is probably valid. By “probably valid” what we mean is this: if an attacker gives us a block that is determined to be probably valid, but is not actually valid, then the attacker needs to pay a high cost for doing so. Even if the attacker succeeds in temporarily fooling a light client or wasting its time, the attacker should still suffer more than the victims of the attack. This is the standard that we will apply to proof of work, and proof of stake, equally.

In proof of work, the process is simple. The core idea behind proof of work is that there exists a mathematical function which a block header must satisfy in order to be valid, and it is computationally very intensive to produce such a valid header. If a light client was offline for some period of time, and then comes back online, then it will look for the longest chain of valid block headers, and assume that that chain is the legitimate blockchain. The cost of spoofing this mechanism, providing a chain of block headers that is probably-valid-but-not-actually-valid, is very high; in fact, it is almost exactly the same as the cost of launching a 51% attack on the network.

In Bitcoin, this proof of work condition is simple: sha256(block_header) < 2**187 (in practice the “target” value changes, but once again we can dispense of this in our simplified analysis). In order to satisfy this condition, miners must repeatedly try different nonce values until they come upon one such that the proof of work condition for the block header is satisfied; on average, this consumes about 269 computational effort per block. The elegant feature of Bitcoin-style proof of work is that every block header can be verified by itself, without relying on any external information at all. This means that the process of validating the block headers can in fact be done in constant time – download 80 bytes and run a hash of it – even better than the logarithmic bound that we have established for ourselves. In proof of stake, unfortunately we do not have such a nice mechanism.

Light Clients in Proof of Stake

If we want to have an effective light client for proof of stake, ideally we would like to achieve the exact same complexity-theoretic properties as proof of work, although necessarily in a different way. Once a block header is trusted, the process for accessing any data from the header is the same, so we know that it will take a logarithmic amount of time in order to do. However, we want the process of validating the block headers themselves to be logarithmic as well.

To start off, let us describe an older version of Slasher, which was not particularly designed to be explicitly light-client friendly:

- In order to be a “potential blockmaker” or “potential signer”, a user must put down a security deposit of some size. This security deposit can be put down at any time, and lasts for a long period of time, say 3 months.

- During every time slot

T(eg.T= 3069120 to 3069135 seconds after genesis), some function produces a random numberR(there are many nuances behind making the random number secure, but they are not relevant here). Then, suppose that the set of potential signersps(stored in a separate Merkle tree) has sizeN. We takeps[sha3(R) % N]as the blockmaker, andps[sha3(R + 1) % N],ps[sha3(R + 2) % N]…ps[sha3(R + 15) % N]as the signers (essentially, usingRas entropy to randomly select a signer and 15 blockmakers) - Blocks consist of a header containing (i) the hash of the previous block, (ii) the list of signatures from the blockmaker and signers, and (iii) the Merkle root of the transactions and state, as well as (iv) auxiliary data like the timestamp.

- A block produced during time slot

Tis valid if that block is signed by the blockmaker and at least 10 of the 15 signers. - If a blockmaker or signer legitimately participates in the blockmaking process, they get a small signing reward.

- If a blockmaker or signer signs a block that is not on the main chain, then that signature can be submitted into the main chain as “evidence” that the blockmaker or signer is trying to participate in an attack, and this leads to that blockmaker or signer losing their deposit. The evidence submitter may receive 33% of the deposit as a reward.

Unlike proof of work, where the incentive not to mine on a fork of the main chain is the opportunity cost of not getting the reward on the main chain, in proof of stake the incentive is that if you mine on the wrong chain you will get explicitly punished for it. This is important; because a very large amount of punishment can be meted out per bad signature, a much smaller number of block headers are required to achieve the same security margin.

Now, let us examine what a light client needs to do. Suppose that the light client was last online N blocks ago, and wants to authenticate the state of the current block. What does the light client need to do? If a light client already knows that a block B[k] is valid, and wants to authenticate the next block B[k+1], the steps are roughly as follows:

- Compute the function that produces the random value

Rduring blockB[k+1](computable either constant or logarithmic time depending on implementation) - Given

R, get the public keys/addresses of the selected blockmaker and signer from the blockchain’s state tree (logarithmic time) - Verify the signatures in the block header against the public keys (constant time)

And that’s it. Now, there is one gotcha. The set of potential signers may end up changing during the block, so it seems as though a light client might need to process the transactions in the block before being able to compute ps[sha3(R + k) % N]. However, we can resolve this by simply saying that it’s the potential signer set from the start of the block, or even a block 100 blocks ago, that we are selecting from.

Now, let us work out the formal security assurances that this protocol gives us. Suppose that a light client processes a set of blocks, B[1] ... B[n], such that all blocks starting from B[k + 1] are invalid. Assuming that all blocks up to B[k] are valid, and that the signer set for block B[i] is determined from block B[i - 100], this means that the light client will be able to correctly deduce the signature validity for blocks B[k + 1] ... B[k + 100]. Hence, if an attacker comes up with a set of invalid blocks that fool a light client, the light client can still be sure that the attacker will still have to pay ~1100 security deposits for the first 100 invalid blocks. For future blocks, the attacker will be able to get away with signing blocks with fake addresses, but 1100 security deposits is an assurance enough, particularly since the deposits can be variably sized and thus hold many millions of dollars of capital altogether.

Thus, even this older version of Slasher is, by our definition, light-client-friendly; we can get the same kind of security assurance as proof of work in logarithmic time.

A Better Light-Client Protocol

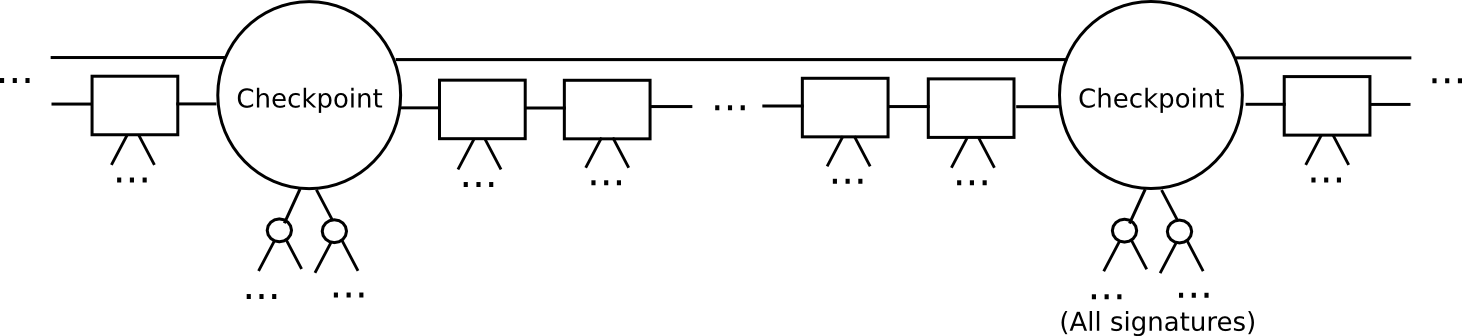

However, we can do significantly better than the naive algorithm above. The key insight that lets us go further is that of splitting the blockchain up into epochs. Here, let us define a more advanced version of Slasher, that we will call “epoch Slasher”. Epoch Slasher is identical to the above Slasher, except for a few other conditions:

- Define a checkpoint as a block such that

block.number % n == 0(ie. everynblocks there is a checkpoint). Think ofnas being somewhere around a few weeks long; it only needs to be substantially less than the security deposit length. - For a checkpoint to be valid, 2/3 of all potential signers have to approve it. Also, the checkpoint must directly include the hash of the previous checkpoint.

- The set of signers during a non-checkpoint block should be determined from the set of signers during the second-last checkpoint.

This protocol allows a light client to catch up much faster. Instead of processing every block, the light client would skip directly to the next checkpoint, and validate it. The light client can even probabilistically check the signatures, picking out a random 80 signers and requesting signatures for them specifically. If the signatures are invalid, then we can be statistically certain that thousands of security deposits are going to get destroyed.

After a light client has authenticated up to the latest checkpoint, the light client can simply grab the latest block and its 100 parents, and use a simpler per-block protocol to validate them as in the original Slasher; if those blocks end up being invalid or on the wrong chain, then because the light client has already authenticated the latest checkpoint, and by the rules of the protocol it can be sure that the deposits at that checkpoint are active until at least the next checkpoint, once again the light client can be sure that at least 1100 deposits will be destroyed.

With this latter protocol, we can see that not only is proof of stake just as capable of light-client friendliness as proof of work, but moreover it’s actually even more light-client friendly. With proof of work, a light client synchronizing with the blockchain must download and process every block header in the chain, a process that is particularly expensive if the blockchain is fast, as is one of our own design objectives. With proof of stake, we can simply skip directly to the latest block, and validate the last 100 blocks before that to get an assurance that if we are on the wrong chain, at least 1100 security deposits will be destroyed.

Now, there is still a legitimate role for proof of work in proof of stake. In proof of stake, as we have seen, it takes a logarithmic amount of effort to probably-validate each individual block, and so an attacker can still cause light clients a logarithmic amount of annoyance by broadcasting bad blocks. Proof of work alone can be effectively validated in constant time, and without fetching any data from the network. Hence, it may make sense for a proof of stake algorithm to still require a small amount of proof of work on each block, ensuring that an attacker must spend some computational effort in order to even slightly inconvenience light clients. However, the amount of computational effort required to compute these proofs of work will only need to be miniscule.

The post Light Clients and Proof of Stake appeared first on .

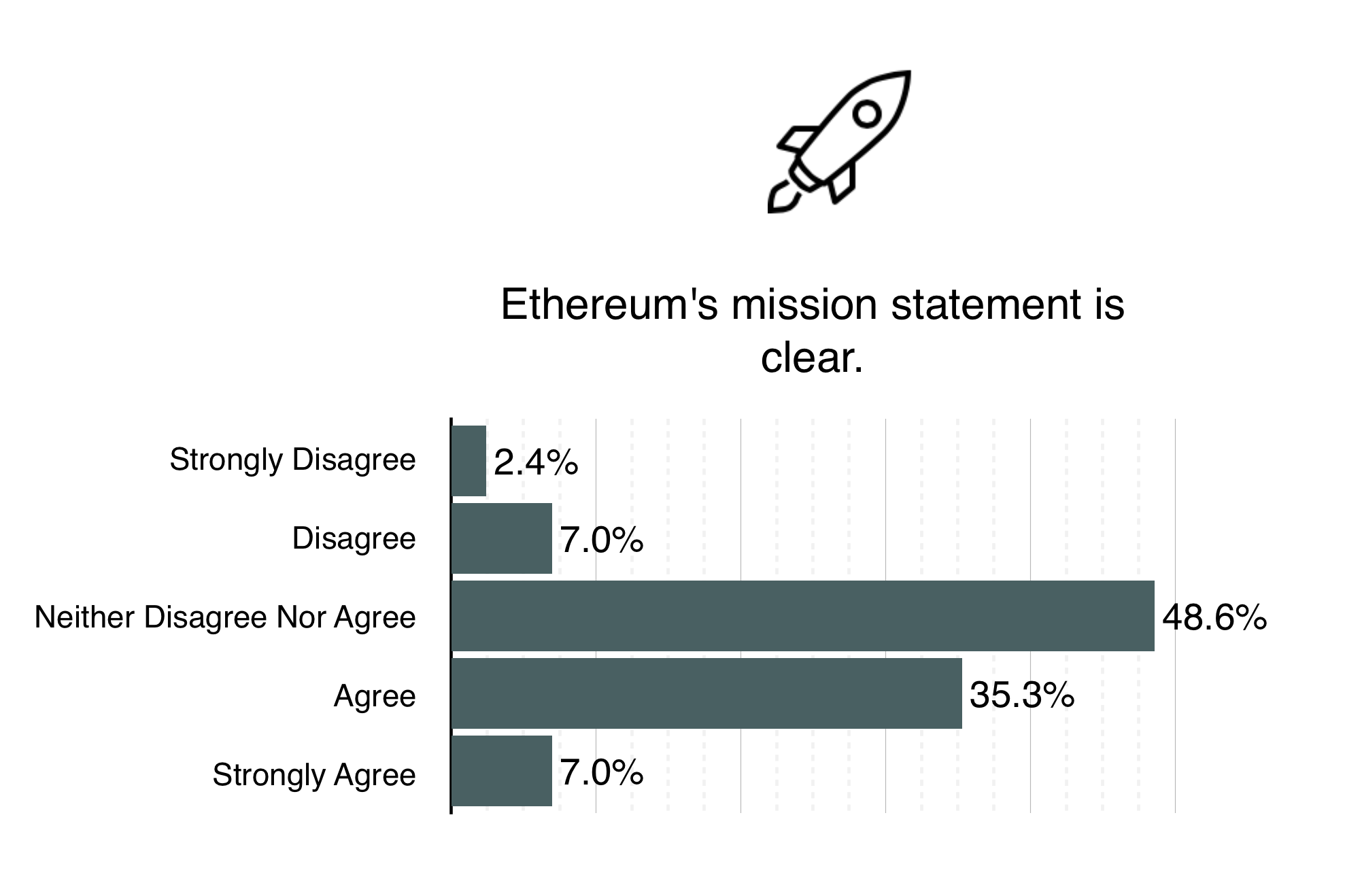

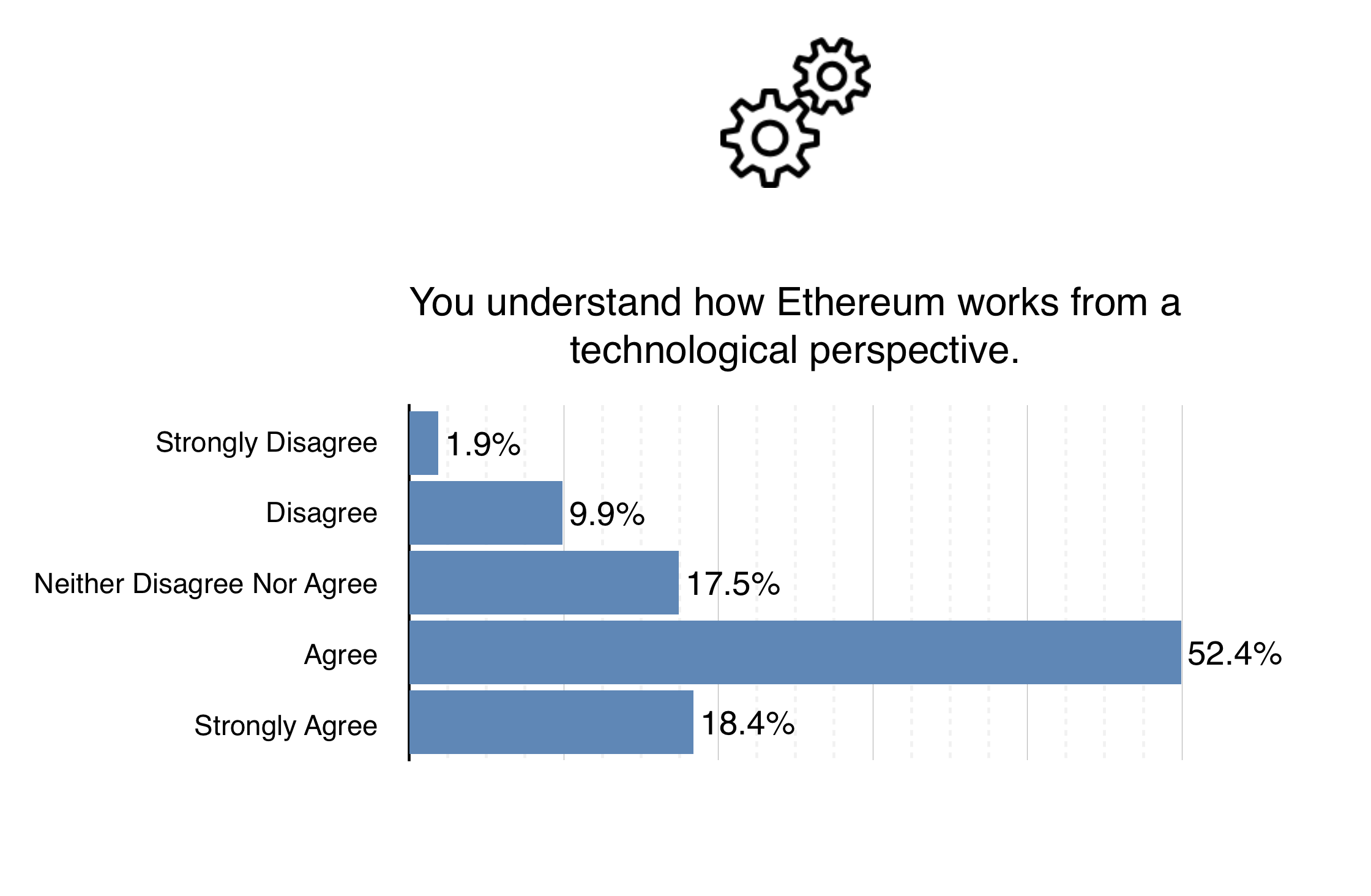

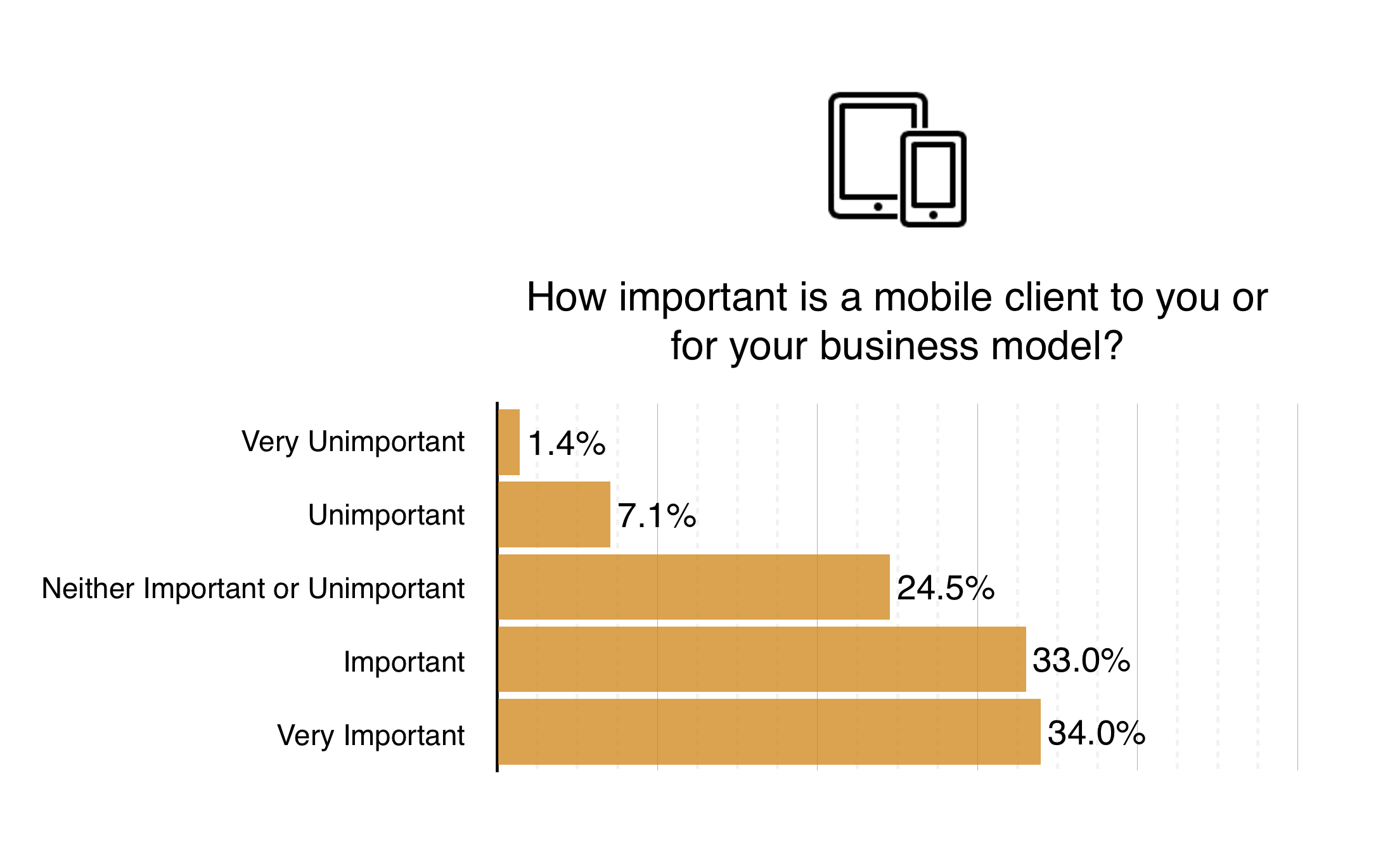

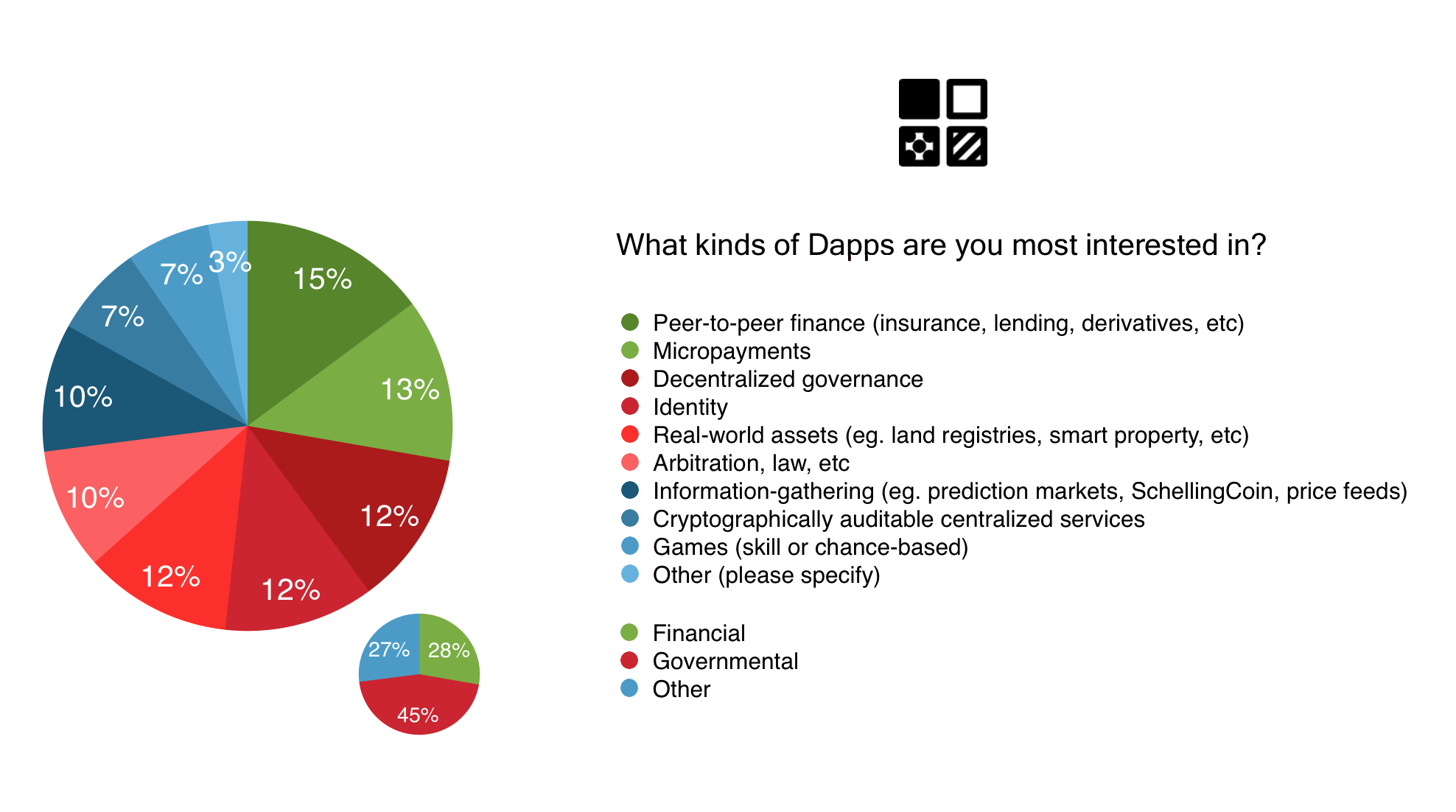

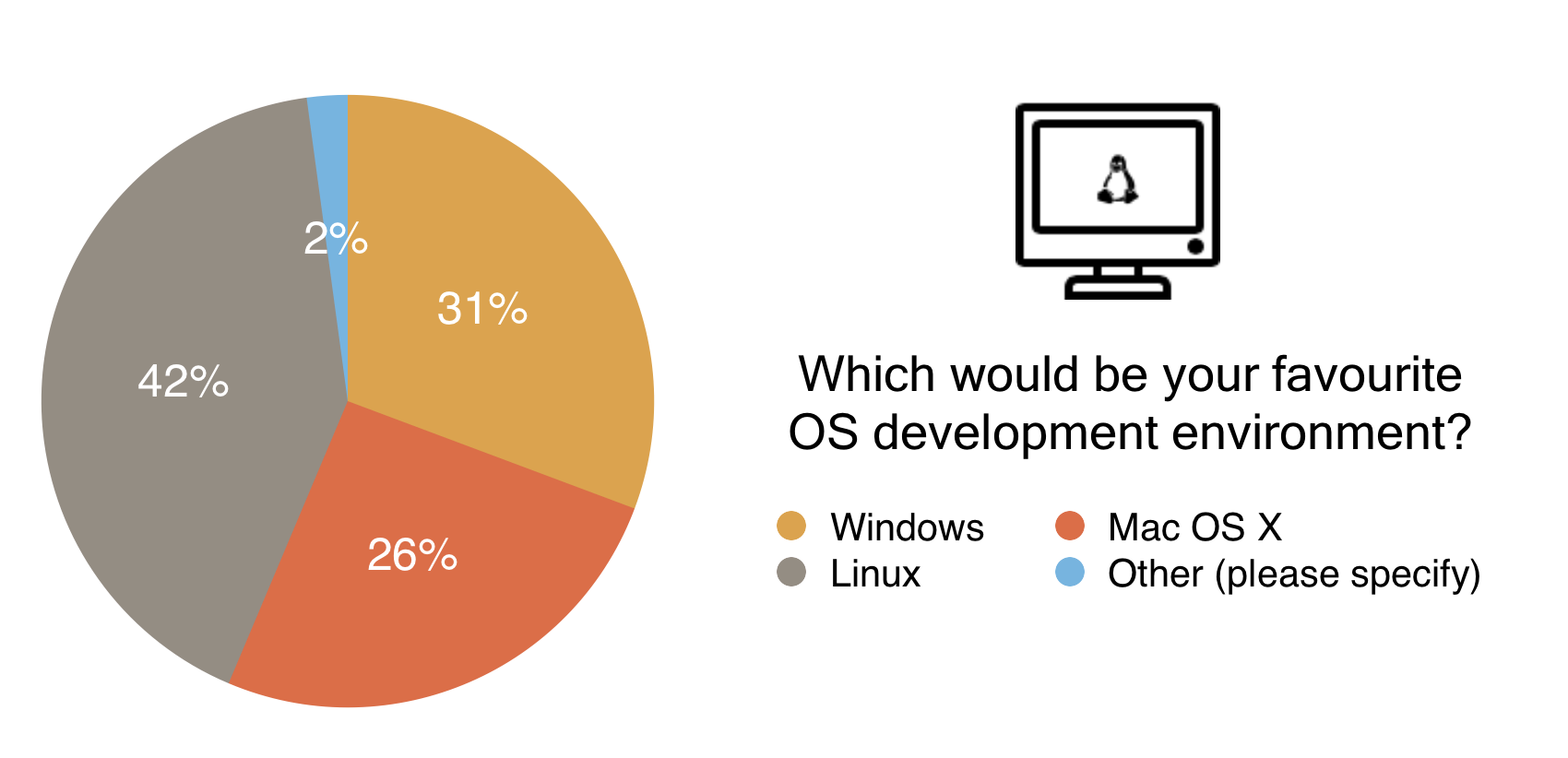

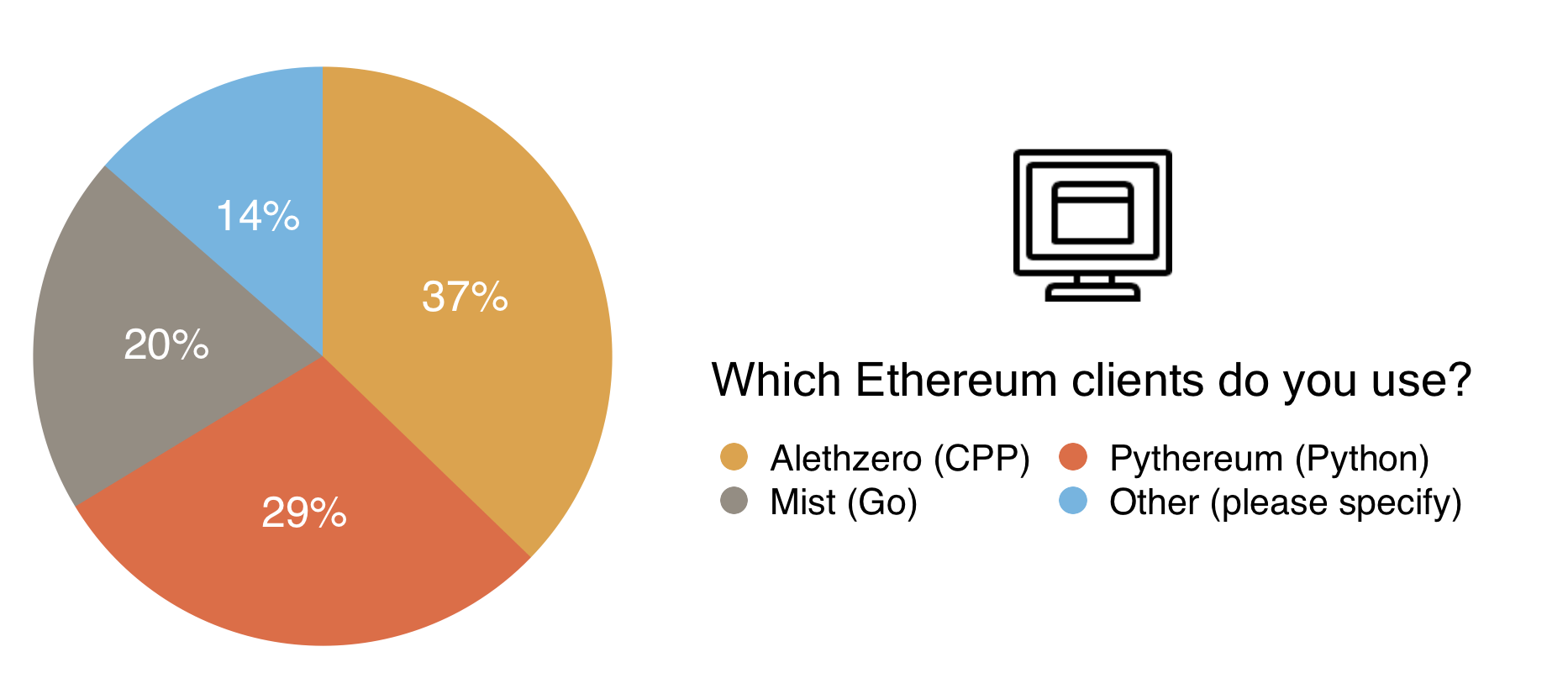

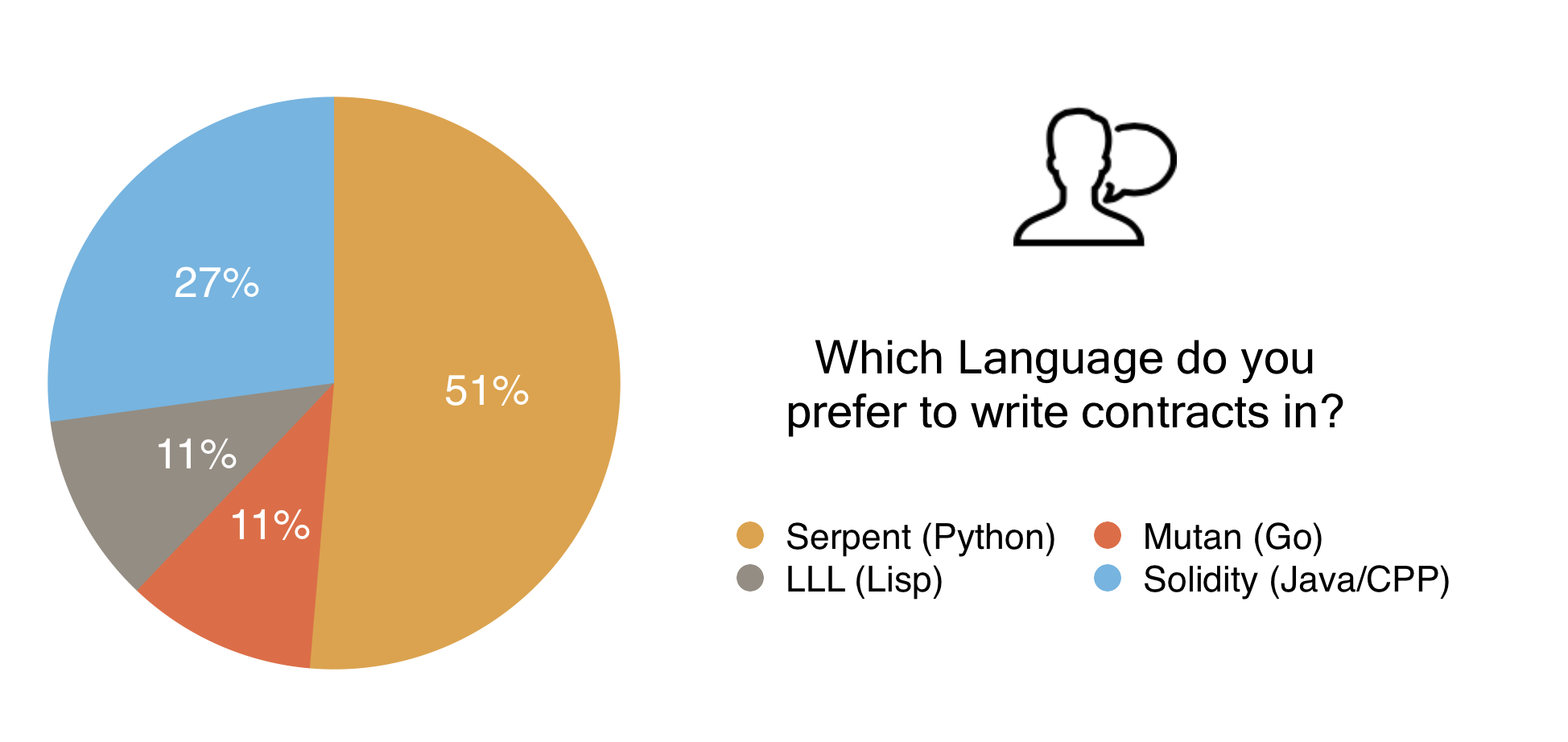

Back in November, we created a quick survey for the Ethereum community to help us gauge how we’re doing, what can be improved, and how best we can engage with you all as we move forward towards the genesis block release in March. We feel it’s very important to enable the community to interact with Ethereum as well as itself, and we hope to offer new and exciting tools to do so using the survey results for guidance.

The survey itself consisted of 14 questions split into two sections; Ethereum as an “Organisation” and Ethereum as a “Technology”. There was a total of 286 responses. This represents 7.8% of the current Ethereum reddit population, or 2.4% of the current @ethereumproject followers.

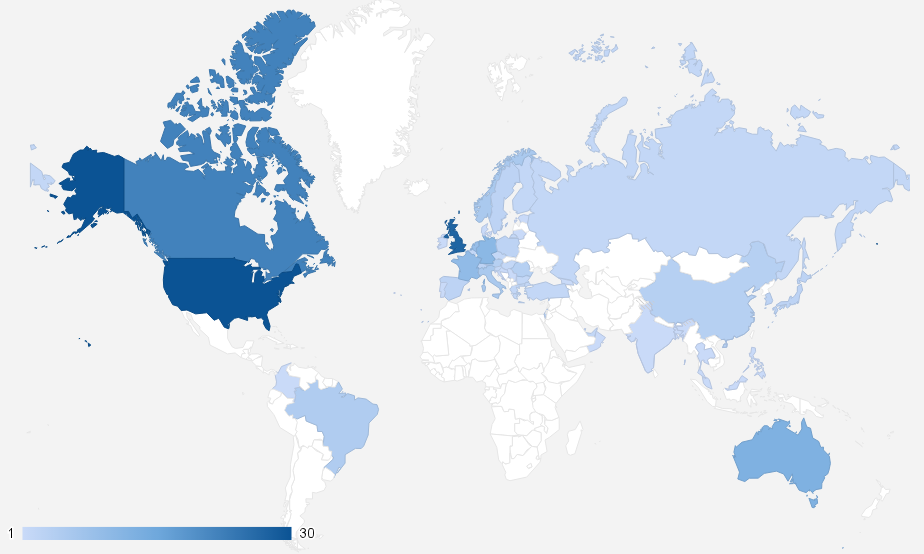

What country do you currently reside in?

So, this is where everybody lives. To sum it up by continent – of the 286 respondents there are 123 (43%) in North America, 114 (40%) in Europe, 30 (10%) in Asia, 13 (5%) in Oceana and 6 (2%) in South America. No surprises there, though it does show how we – and the crypto space in general – have much work to do in areas south of the Brandt Line. One way to go about this is to seed more international Ethereum meetups. You can see a map of all the current Ethereum meetups here (We have 81 in total all over the world from London to New York to Tehran with over 6000 members taking part). If you’d like to start one yourself, please do message us and we can offer further assistance – .

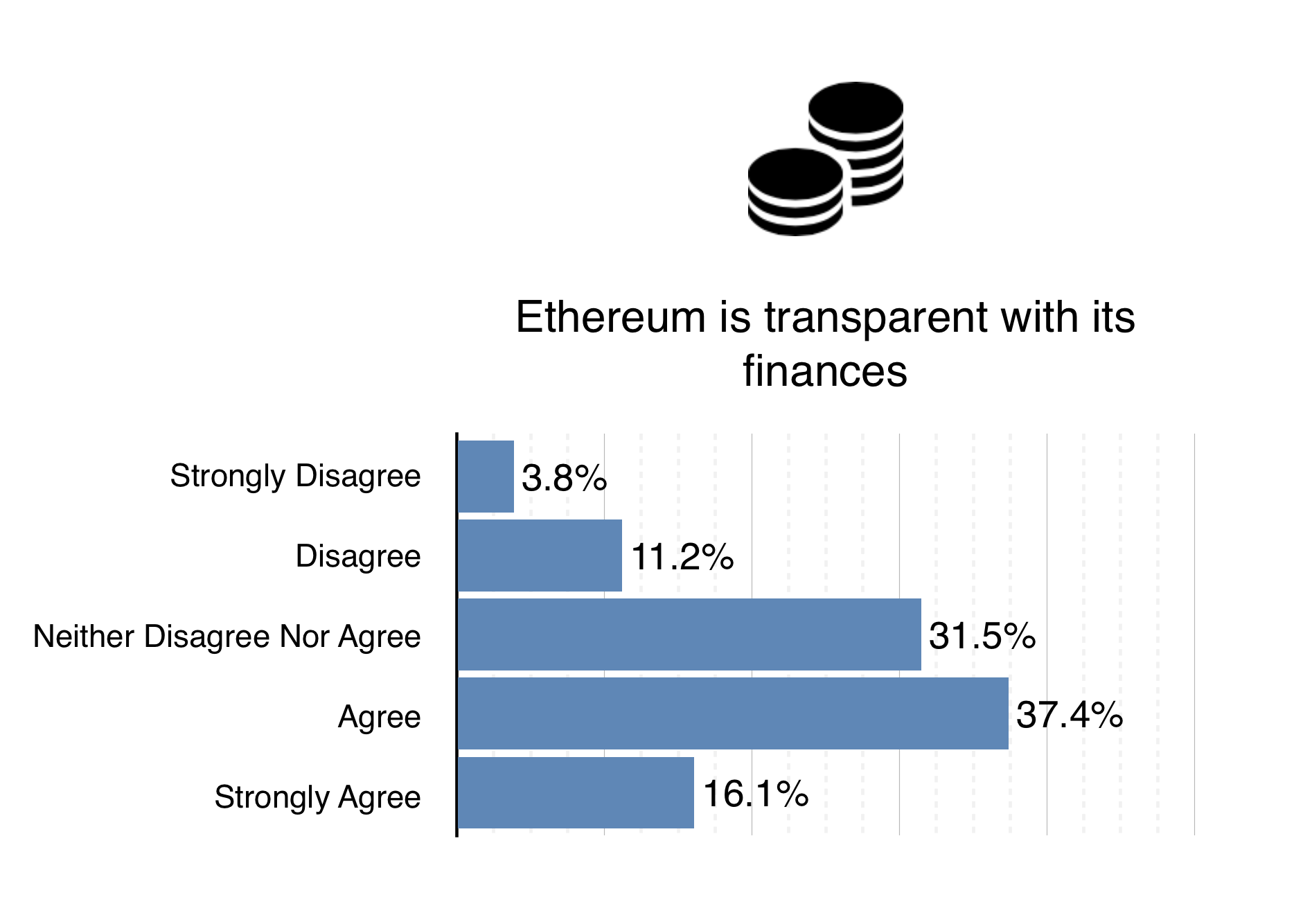

It’s understood that our transparency is very important to the community. To that end, we strive to make much of our internal workings freely available on the internet. As indicated in the chart, most people agree that we are doing just that. However, more can always be done. We’re currently working on a refresh of the ethereum.org website ready for the release of the genesis block. Expect much more content and information as we complete this towards the end of January. In the meantime, have a look at the Ethereum GitHub Repository, or head over to the new ΞTH ÐΞV website for a greater understanding of the entity that is delivering Ethereum 1.0, as well as its truly incredible team.

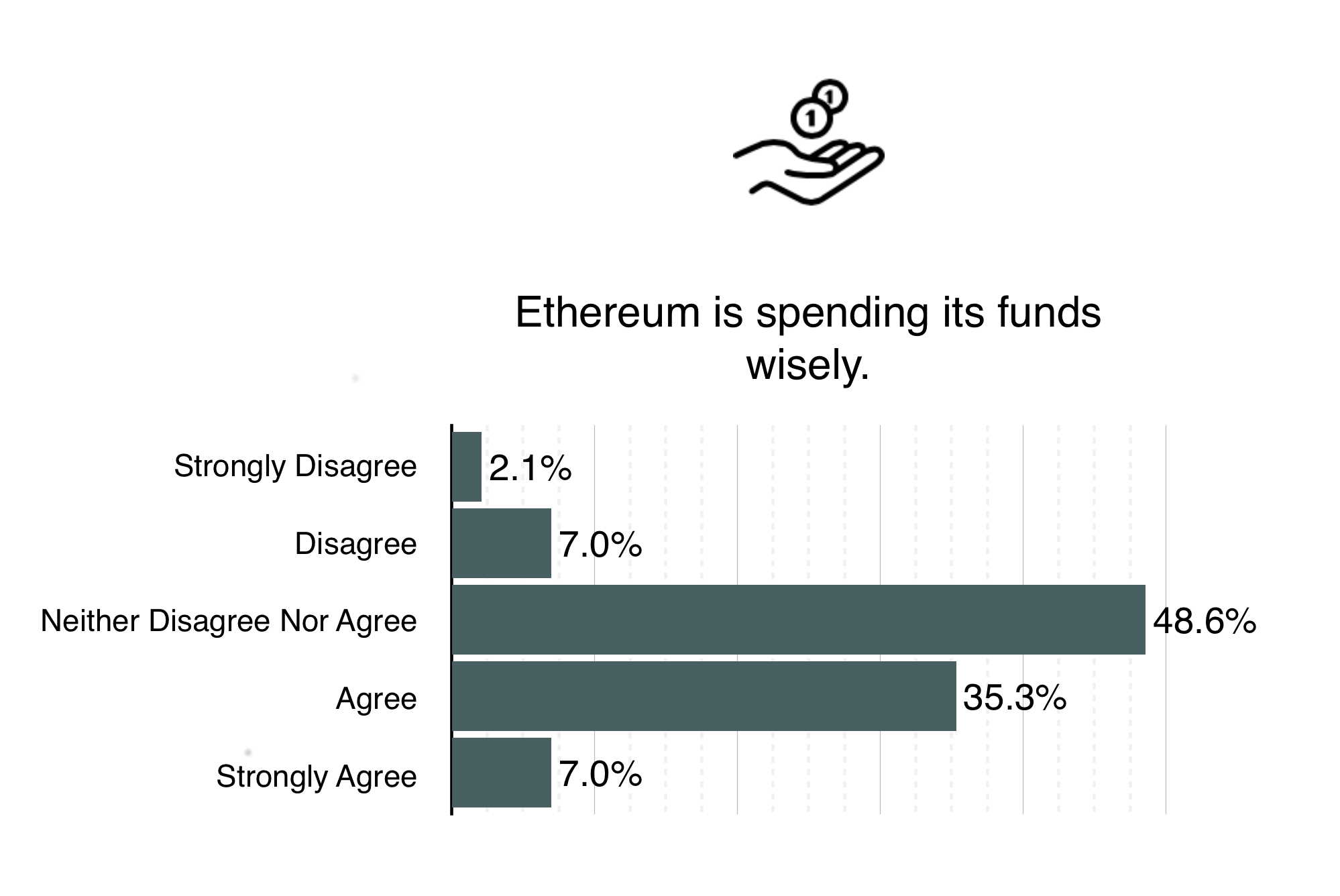

We’ve always tried to give the community as much information about our financial situation as possible, and from the results it seems like a lot of you agree. For further information on how Ethereum intends to use the funds raised in the Ether sale as we move forward, check out the Road Map and the ĐΞV PLAN. To learn more about the Ether Sale itself, have a look at Vitalik’s Ether Sale Introduction, the Ethereum Bitcoin Wallet, or the Ether Sale Statistical Overview.

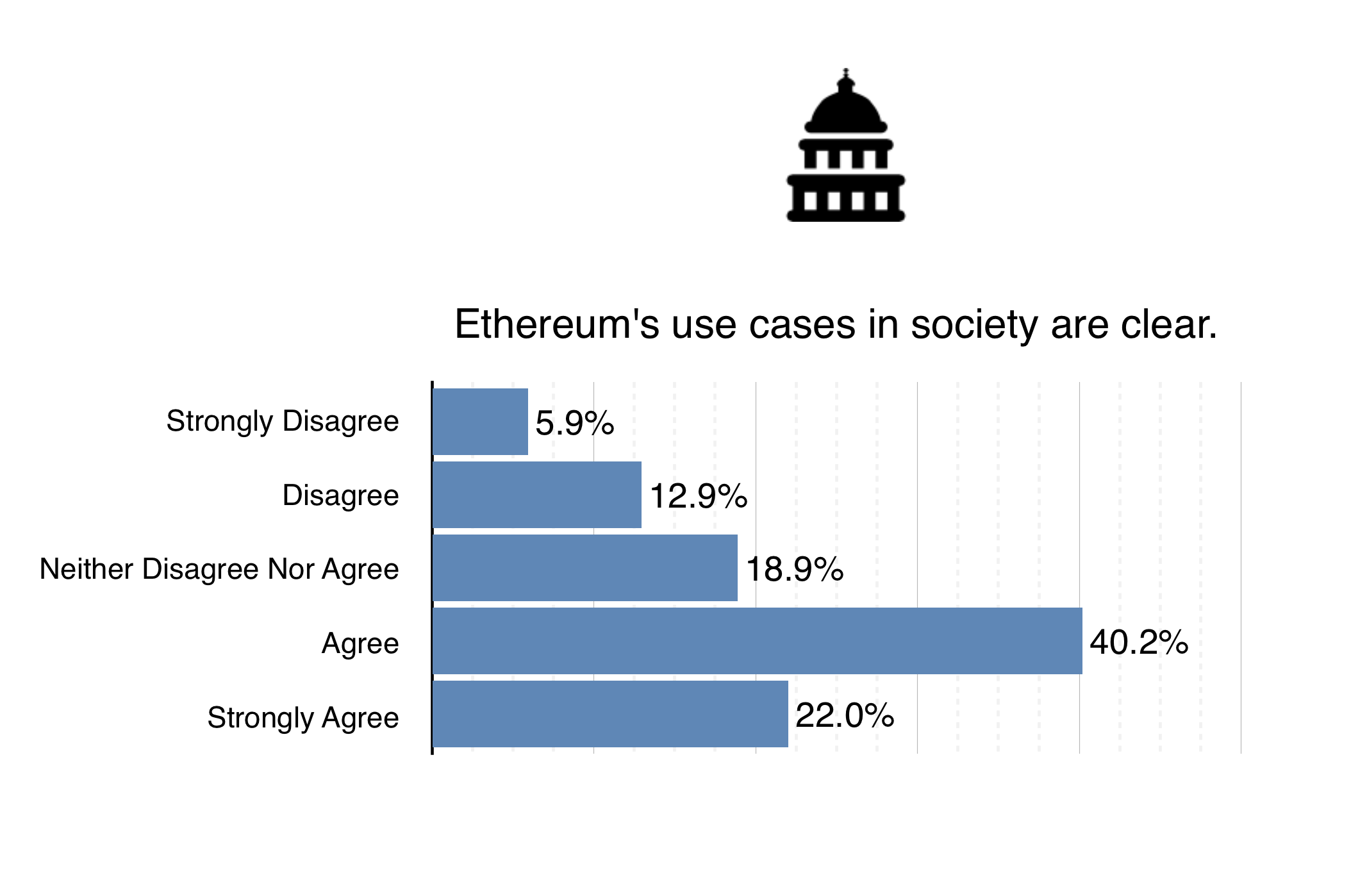

Though most people agree Ethereum’s use cases in society are clear, I wouldn’t be so sure we’ve figured them all out just yet. Everyday we’re speaking with developers and entrepreneurs via Skype or on IRC (Join in your browser – #ethereum / #ethereum-dev) who have thought of new and exciting ideas that they are looking to implement on top of Ethereum – many of which are brand new to us. For a brief overview of some of the use cases we’ve encountered, check out Stephan Tual’s recent presentation at NewFinance.

We’re doing our best to keep everyone updated with the plethora of changes, updates and general progression of the project that’s been taking place over the recent months. Gavin Wood and Jeff Wilcke especially have written some excellent blog updates on how things are going in their respective Berlin and Amsterdam ÐΞV Hubs. You can see all of the updates in the Project category of the Ethereum blog.

ΞTH ÐΞV’s mission statement is now proudly presented on the ΞTH ÐΞV website for all to see. In detail, it explains what needs to be achieved as time goes on, but can be summed up as “To research, design and build software that, as best as possible, facilitates, in a secure, decentralised and fair manner, the communication and automatically-enforced agreement between parties.”

Much like the crypto space in general, Ethereum is somewhat difficult to initially get your head around. No doubt about that, and it’s our job to make the process of gaining understanding and enabling participation as easy and intuitive as possible. As mentioned previously, the new look ethereum.org website will be an invaluable tool in helping people access the right information that is applicable to their own knowledge and skill set. Also, in time we aim to create a Udemy/Codacademy like utility which will allow people with skills ranging from none to Jedi Master to learn how Ethereum works and how to implement their ideas. In the mean time, a great place to start for those wanting to use Ethereum is Ken Kappler’s recent Tutorials.

This was an important question as it gave a lot of perspective on what aspects needed to be focused on before genesis, and what (though useful) could be developed afterwards. From a UI point of view, the Go team in Amsterdam is working towards the creation of Mist, Ethereum’s “Ðapp Navigator”. Mist’s initial design ideas are presented by the Lead UI Designer, Alex Van de Sande in this video.

Ease of installation will factor greatly in user adoption – we cant very well have people recompiling the client every time a new update is pushed! So binaries with internal update systems are in the pipeline. Client Reliability (bugs) is being actioned on by Jutta Steiner, the Manager of our internal and external security audits. We expect the community bug bounty project to be live by the middle of January, so stay tuned and be ready for epic 11 figure Satoshi rewards, leaderboards and more “1337” prizes.

Developer tools are on the way too. Specifically, project “Mix”. Mix supports some rather amazing features, including documentation, a compiler, debugger integration for writing information on code health, valid invariant, code structure and code formatting, as well as variable values and assertion truth annotations. It’s a long term project expected to be delivered in the next 12-18 months, right now we are very much focused on completing the blockchain. Once complete, we can reallocate our resources to other important projects. You can find out more in the Mix presentation from ÐΞVcon-0. For now, documentation is constantly being generated on the Ethereum GitHub Wiki.

The blog and social media interaction will continue to deliver Ethereum content on relevant channels with the aim of reaching the widest range of people as possible.

With more people owning smartphones than computers already, imagine how prolific they’ll will be as time goes on? This will be the case especially in emerging markets such as India and Nigeria, it’s likely they’ll leapfrog computers to some extent and gain wide adoption very quickly. A mobile light client will be greatly important to the usability of Ethereum. As part of IBM and Samsung’s joint project “Adept” (an IoT platform which is currently being unveiled at CES 2015), an Android version of the Ethereum Java client – ethereumj, is going to be open-sourced on GitHub. This will go a long way to getting Ethereum Mobile!

It’s interesting to see a very mixed bag of responses for this question. As was said previously, Ethereum’s use cases are as wide as they are varied, and it’s great to see how many different types of services people are looking to implement on top of Ethereum. The emphasis on governance based Ðapps highlights Ethereum’s ability to facilitate interactions between the digital and physical world and create autonomously governed communities that can compete with both governments and corporations. Primavera De Filippi and Raffaele Mauro investigate this further in the Internet Policy Review Journal.

This chart shows a reasonably even spread, we’ve done our best to make the various clients available on different operating systems. You can find the Alethzero binaries here, and the Mist binaries here. These however become obsolete very quickly and may not connect to the test net as development continues, so if you considering using Ethereum before release, it’s well worth while checking the client building tutorials to get the most up to date versions of the clients.

With Mist (Go), Alethzero (C++), Pythereum (Python) Node-Ethereum (Node.js), and Ethereumj (Java), Ethereum already has a plethora of clients available. The Yellow Paper written by Gavin Wood is a great reference for the community to create its own clients, as seen with those still under development such as the Clojure and Objective C iterations.

As Gavin Wood has mentioned in a previous blogpost, Mutan and LLL as smart contract languages will be mothballed. Serpent will be continued to be developed by Vitalik with his team, and Soldity will continue as the primary development language for Ethereum contracts. You can try Solidity in your browser, or watch the recent vision and roadmap presentation by Gavin Wood and Vitalik Buterin at ÐΞVcon-0.

Thanks to Alex Van de Sande for helping with the implementation of the survey and chart graphics. Icons retrieved from icons8. If anyone would like a copy of the raw survey results, feel free to email .

The post Ethereum Community Survey appeared first on .

First of all, happy new year! What a year it has been. With a little luck we’ll surpass last year with an even more awesome year. It’s been too long since I’ve given an update on my side of things and that of the Go team and mostly due to a lack of time. I’ve been so incredibly busy and so many things have happened these past 2 months I’ve hardly had time to sit down and assess it all.

As you may be well aware the audit is looming around the corner and my little baby (go-ethereum!) will undergo it’s full inspection very, very soon. The audit teams will tear it apart and see if the repo contains anything incorrectly implemented as well as search for any major security flaws in the design and implementation. We’ve been pretty solid on tests, testing implementation details as well as consensus tests (thanks to Christoph) and will continue to add more tests over time. We’ll see how they hold up during the audit (though I’m confident we’ll be fine, it’s still a little bit scary (-:)

Development

PoC-7 has been released now for a about a week and has been quite stable (and growing in size!). We’re already hard at work to finalising PoC-8 which includes numerous small changes:

- Adjusted block time back to

12s(was4s) - Op code

PREVHASHhas becomeBLOCKHASH( N )and thereforePREVHASH = BLOCKHASH(NUMBER - 1) - We’ve added an additional pre-compiled contract at address 0x04 which returns the given input (acts like copy / memcpy)

Ongoing

P2P

Felix has been hard at work on our new P2P package which has now entered in to v0.1 (PoC-7) and will soon already undergo it’s first upgrade for PoC-8. Felix has done an amazing job on the design of the package and it’s a real pleasure to work with. Auto-generated documentation can be found at GoDoc.

Whisper

A month or so back I finished the first draft of Whisper for the Go implementation and it’s now passing whisper messages nicely around the network and uses the P2P package mentioned earlier. The Go API is relatively easy and requires almost zero setup.

Backend

The backend stack of ethereum has also received its first major (well deserved) overhaul. Viktor’s been incredibly hard at work to reimplement the download manager and the ethereum sub protocol.

Swarm

Since the first day Dani joined the team he’s passionately been working on the peer selection algorithm and distributed preimage archive. The DPA will be used for our Swarm tech. The spec is about 95% complete and roughly about 50% has been implemented. Progress is going strong!

Both go-ethereum/p2p and go-ethereum/whisper have been developed in such a way that neither require ethereum to operate. If you’re developing in Go and your application requires a P2P network or (dark) messaging try out the packages. An example sub protocol can be found here and an example on how to use Whisper can be found here.

Ams Hub

Now that the hub is finally set up you’re free to drop by and grab a coffee with us. You can find us in the rather posh neighbourhood of Amsterdam Zuid near Museumplein (Alexander Boerstraat 21).

In my next post I hope I’ll have a release candidate for PoC-8 and perhaps even a draft implementation of swarm. But until then, happy whispering and mining!

The post Jeff’s Ethereum ÐΞV Update II appeared first on ethereum blog.

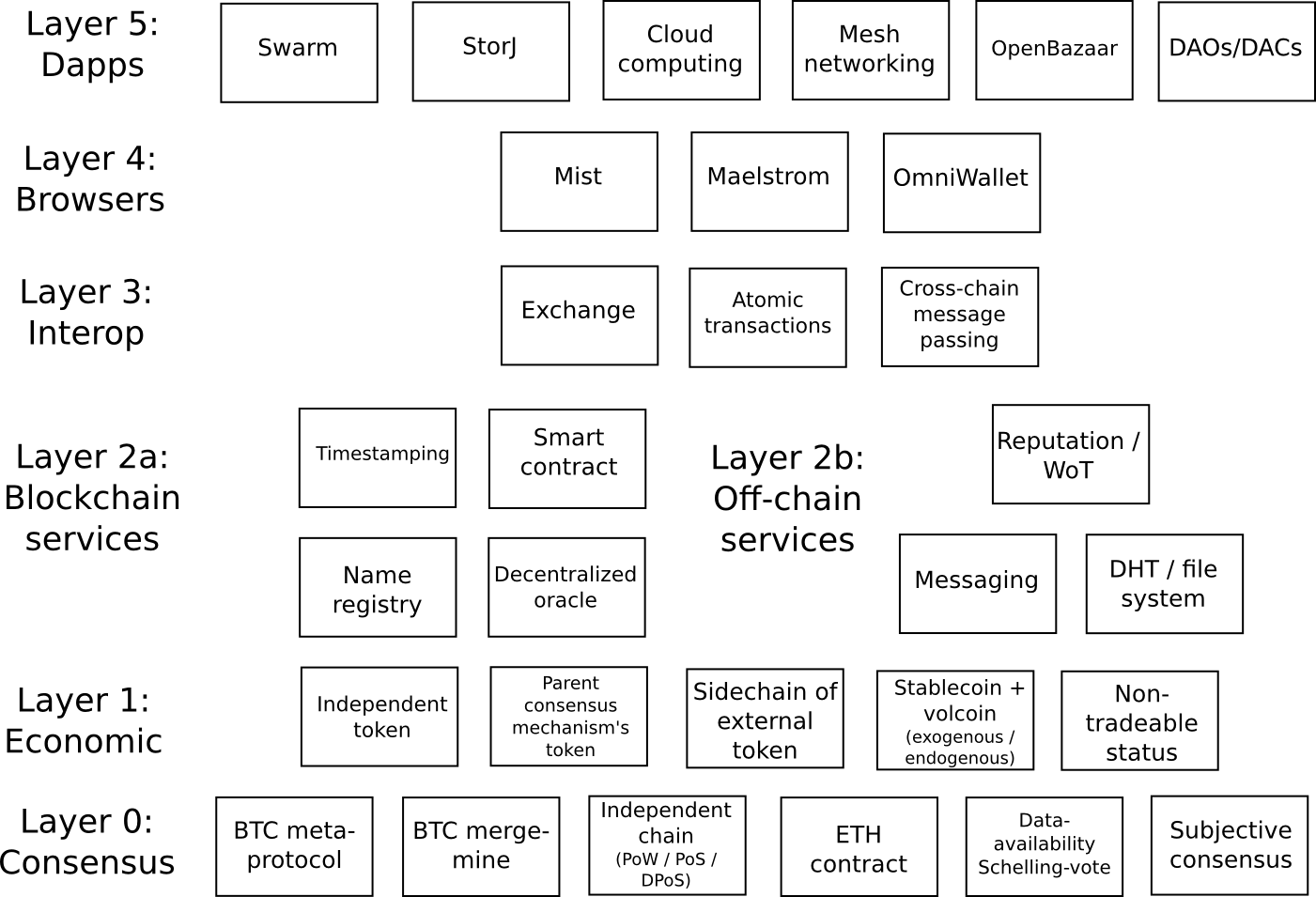

One of the criticisms that many people have made about the current direction of the cryptocurrency space is the increasing amount of fragmentation that we are seeing. What was earlier perhaps a more tightly bound community centered around developing the common infrastructure of Bitcoin is now increasingly a collection of “silos”, discrete projects all working on their own separate things. There are a number of developers and researchers who are either working for Ethereum or working on ideas as volunteers and happen to spend lots of time interacting with the Ethereum community, and this set of people has coalesced into a group dedicated to building out our particular vision. Another quasi-decentralized collective, Bitshares, has set their hearts on their own vision, combining their particular combination of DPOS, market-pegged assets and vision of blockchain as decentralized autonomous corporation as a way of reaching their political goals of free-market libertarianism and a contract free society. Blockstream, the company behind “sidechains”, has likewise attracted their own group of people and their own set of visions and agendas – and likewise for Truthcoin, Maidsafe, NXT, and many others.

One argument, often raised by Bitcoin maximalists and sidechains proponents, is that this fragmentation is harmful to the cryptocurrency ecosystem – instead of all going our own separate ways and competing for users, we should all be working together and cooperating under Bitcoin’s common banner. As Fabian Brian Crane summarizes:

One recent event that has further inflamed the discussion is the publication of the sidechains proposal. The idea of sidechains is to allow the trustless innovation of altcoins while offering them the same monetary base, liquidity and mining power of the Bitcoin network.

For the proponents, this represents a crucial effort to rally the cryptocurrency ecosystem behind its most successful project and to build on the infrastructure and ecosystem already in place, instead of dispersing efforts in a hundred different directions.

Even to those who disagree with Bitcoin maximalism, this seems like a rather reasonable point, and even if the cryptocurrency community should not all stand together under the banner of “Bitcoin” one may argue that we need to all stand together somehow, working to build a more unified ecosystem. If Bitcoin is not powerful enough to be a viable backbone for life, the crypto universe and everything, then why not build a better and more scalable decentralized computer instead and build everything on that? Hypercubes certainly seem powerful enough to be worth being a maximalist over, if you’re the sort of person to whom one-X-to-rule-them-all proposals are intuitively appealing, and the members of Bitshares, Blockstream and other “silos” are often quite eager to believe the same thing about their own particular solutions, whether they are based on merged-mining, DPOS plus BitAssets or whatever else.

So why not? If there truly is one consensus mechanism that is best, why should we not have a large merger between the various projects, come up with the best kind of decentralized computer to push forward as a basis for the crypto-economy, and move forward together under one unified system? In some respects, this seems noble; “fragmentation” certainly has undesirable properties, and it is natural to see “working together” as a good thing. In reality, however, while more cooperation is certainly useful, and this blog post will later describe how and why, desires for extreme consolidation or winner-take-all are to a large degree exactly wrong – not only is fragmentation not all that bad, but rather it’s inevitable, and arguably the only way that this space can reasonably prosper.

Agree to Disagree

Why has fragmentation been happening, and why should we continue to let it happen? To the first question, and also simultaneously to the second, the answer is simple: we fragment because we disagree. Particularly, consider some of the following claims, all of which I believe in, but which are in many cases a substantial departure from the philosophies of many other people and projects:

- I do not think that weak subjectivity is all that much of a problem. However, mugh higher degrees of subjectivity and intrinsic reliance on extra-protocol social consensus I am still not comfortable with.

- I consider Bitcoin’s $ 600 million/year wasted electricity on proof of work to be an utter environmental and economic tragedy.

- I believe ASICs are a serious problem, and that as a result of them Bitcoin has become qualitatively less secure over the past two years.

- I consider Bitcoin (or any other fixed-supply currency) to be too incorrigibly volatile to ever be a stable unit of account, and believe that the best route to cryptocurrency price stability is by experimenting with intelligently designed flexible monetary policies (ie. NOT “the market” or “the Bitcoin central bank“). However, I am not interested in bringing cryptocurrency monetary policy under any kind of centralized control.

- I have a substantially more anti-institutional/libertarian/anarchistic mindset than some people, but substantially less so than others (and am incidentally not an Austrian economist). In general, I believe there is value to both sides of the fence, and believe strongly in being diplomatic and working together to make the world a better place.

- I am not in favor of there being one-currency-to-rule-them-all, in the crypto-economy or anywhere.

- I think token sales are an awesome tool for decentralized protocol monetization, and that everyone attacking the concept outright is doing a disservice to society by threatening to take away a beautiful thing. However, I do agree that the model as implemented by us and other groups so far has its flaws and we should be actively experimenting with different models that try to align incentives better

- I believe futarchy is promising enough to be worth trying, particularly in a blockchain governance context.

- I consider economics and game theory to be a key part of cryptoeconomic protocol analysis, and consider the primary academic deficit of the cryptocurrency community to be not ignorance of advanced computer science, but rather economics and philosophy. We should reach out to http://lesswrong.com/ more.

- I see one of the primary reasons why people will adopt decentralized technologies (blockchains, whisper, DHTs) in practice to be the simple fact that software developers are lazy, and do not wish to deal with the complexities of maintaining a centralized website.

- I consider the blockchain-as-decentralized-autonomous-corporation metaphor to be useful, but limited. Particularly, I believe that we as cryptocurrency developers should be taking advantage of this perhaps brief period in which cryptocurrency is still an idealist-controlled industry to design institutions that maximize utilitarian social welfare metrics, not profit (no, they are not equivalent, primarily because of these).

There are probably very few people who agree with me on every single one of the items above. And it is not just myself that has my own peculiar opinions. As another example, consider the fact that the CTO of OpenTransactions, Chris Odom, says things like this:

What is needed is to replace trusted entities with systems of cryptographic proof. Any entity that you see in the Bitcoin community that you have to trust is going to go away, it’s going to cease to exist … Satoshi’s dream was to eliminate [trusted] entities entirely, either eliminate the risk entirely or distribute the risk in a way that it’s practically eliminated.

Meanwile, certain others feel the need to say things like this:

Put differently, commercially viable reduced-trust networks do not need to protect the world from platform operators. They will need to protect platform operators from the world for the benefit of the platform’s users.

Of course, if you see the primary benefit of cryptocurrency as being regulation avoidance then that second quote also makes sense, but in a way completely different from the way its original author intended – but that once again only serves to show just how differently people think. Some people see cryptocurrency as a capitalist revolution, others see it as an egalitarian revolution, and others see everything in between. Some see human consensus as a very fragile and corruptible thing and cryptocurrency as a beacon of light that can replace it with hard math; others see cryptocurrency consensus as being only an extension of human consensus, made more efficient with technology. Some consider the best way to achieve cryptoassets with dollar parity to be dual-coin financial derivative schemes; others see the simpler approach as being to use blockchains to represent claims on real-world assets instead (and still others think that Bitcoin will eventually be more stable than the dollar all on its own). Some think that scalability is best done by “scaling up“; others believe the ultimately superior option is “scaling out“.

Of course, many of these issues are inherently political, and some involve public goods; in those cases, live and let live is not always a viable solution. If a particular platform enables negative externalities, or threatens to push society into a suboptimal equilibrium, then you cannot “opt out” simply by using your platform instead. There, some kind of network-effect-driven or even in extreme cases 51%-attack-driven censure may be necessary. In some cases, the differences are related to private goods, and are primarily simply a matter of empirical beliefs. If I believe that SchellingDollar is the best scheme for price stability, and others prefer Seignorage Shares or NuBits then after a few years or decades one model will prove to work better, replace its competition, and that will be that.

In other cases, however, the differences will be resolved in a different way: it will turn out that the properties of some systems are better suited for some applications, and other systems better suited for other applications, and everything will naturally specialize into those use cases where it works best. As a number of commentators have pointed out, for decentralized consensus applications in the mainstream financial world, banks will likely not be willing to accept a network managed by anonymous nodes; in this case, something like Ripple will be more useful. But for Silk Road 4.0, the exact opposite approach is the only way to go – and for everything in between it’s a cost-benefit analysis all the way. If users want networks specialized to performing specific functions highly efficiently, then networks will exist for that, and if users want a general purpose network with a high network effect between on-chain applications then that will exist as well. As David Johnston points out, blockchains are like programming languages: they each have their own particular properties, and few developers religiously adhere to one language exclusively – rather, we use each one in the specific cases for which it is best suited.

Room for Cooperation