The LAO: A For-Profit, Limited Liability Autonomous Organization

Source: The LAO – Medium · 11 min read

OpenLaw will be launching the first limited liability for-profit DAO, named the LAO. The LAO will enable members to invest in Ethereum new ventures and generate a profit. A new era of DAOs is beginning.

The LAO: A For-Profit, Limited Liability Autonomous Organization

Since first proposed in 2013, the notion of decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) has animated the dreams of blockchain developers. For many, these Internet-native organizations represent the next step in the evolution of social and economic coordination, with blockchain technology and smart contracts streamlining voting, decision making, and the allocation of digital assets.

The notion of a DAO did not emerge in a vacuum. Instead, these organizations build on a long lineage of technical and legal innovation. The Romans devised a variety of commercial entities, such as the societas peculium and societas publicanorum, that enabled parties to share in an enterprise’s profits and losses while also providing limited liability. During the Middle Ages, Italians pioneered early versions of a limited partnership to finance maritime trade. Joint-stock companies emerged in England and the Netherlands in the 1600s, providing organizations state-granted monopolies to engage in productive commercial enterprises. The modern corporation took root in the United States in 1811, when New York granted private parties the power to form their own corporate structures without an extensive approval process.

These legal innovations helped modernize the globe, allowing individuals from different backgrounds to align incentives towards a common goal. They created a framework for funding new ventures, managing risk, and creating opportunities for profit, which in turn, fueled generations of innovation and wealth creation.

For many, the power of DAOs roots in their ability to reduce transaction costs. As described by Ronald Coase in his landmark 1937 article “The Nature of the Firm,” people exhibit a natural tendency to organize into more or less formalized institutions — associations, partnerships, companies, corporations, or other types of organizations referred to by economists as “firms” when the costs of engaging in market transactions are too high. There are often transaction costs involved in entering into market transactions, including the cost of finding another party to trade with, the cost of negotiation, and all costs related to ensuring that an agreement is performed and, if necessary, enforced. As a result, pulling together different parties to engage in economically beneficial activity can sometimes grow too complex to be handled efficiently through market operations.

While markets often excel at assisting with the rapid exchange of goods or services, they are less useful when an economic activity requires extensive coordination and an ongoing relationship between parties, or when it involves a high degree of complexity or uncertainty. Transaction costs increase when individuals deal with untrusted parties in a marketplace, thus pushing people to organize activity through collaborative endeavors.

By forming an organization, parties reduce transaction costs. Organizations decrease the overall number of operations to complete certain social or economic tasks. And they lower the costs generated by uncertainty, opportunism, and complexity by serving as repeat players in markets and through the creation of agreements that govern the relationships between managers and other members of firms.

The hope with DAOs is that they enable groups to operate more efficiently by relying on smart contracts to govern and coordinate certain actions and behavior. Through the use of smart contracts, parties can automate certain aspects related to the way organizations and groups operate, reducing operational costs and improving internal controls while simultaneously increasing the overall transparency of an organization.

Today, enterprises and corporations are governed and managed mainly or exclusively by legal rules and written documents. With a blockchain, organizations can implement all or parts of the organization’s rules and procedures into code.

The DAO and Its Shortcomings

One of the first substantive experiments with the use of smart contracts to manage and coordinate economic activity was The Decentralized Autonomous Organization (known as The DAO). In early May 2016, The DAO was launched on Ethereum, animating the thoughts and imagination of developers and technologists around the globe. The DAO aimed to operate as a venture capital fund for the crypto and decentralized space. The lack of a centralized authority reduced costs and in theory provided more control and access to the investors.

At the beginning of May 2016, a few members of the Ethereum community announced the inception of The DAO, which was also known as Genesis DAO. It was built as a smart contract on the Ethereum blockchain. The coding framework was developed in open source by the Slock.It team, but it was deployed under “The DAO” name by members of the Ethereum community. The DAO had a creation period during which anyone was allowed to send Ether to a unique wallet address in exchange for DAO tokens on a 1–100 scale. The creation period was an unexpected success as it managed to gather 12.7M Ether (worth $150M at the time), making it the biggest crowdfund ever. If still running, The DAO today would manage assets north of $2 billion.

In essence, the platform would allow anyone with a project to pitch their idea to the community and potentially receive funding from The DAO. Anyone with DAO tokens could vote on plans, and would then receive rewards if the projects turned a profit. With the financing in place, things were looking up.

Despite the potential promise of The DAO to fund promising projects in the Ethereum ecosystem. The DAO lacked a legal structure and ran afoul of U.S. securities laws. As outlined by the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in a 21(a) report, the offer and sales of digital assets by “virtual” organizations are subject to the requirements of the federal securities laws.

In the case of The DAO, the SEC found that The DAO tokens were securities and therefore subject to the federal securities laws. The tokens were offered by a core organization and held out the promise of a profit. As a result, future DAOs that seek to provide members with the opportunity for profit, in general, will need to register offers and sales of such securities unless a valid securities law exemption applies. Any tokens related to the ownership interest of a for-profit DAO must trade on registered exchanges, unless they are exempt, to protect investors and to make sure they receive appropriate disclosures. The SEC reiterated that laws do not evaporate just because an organization relies on blockchain technology.

Separate and apart from the concerns flagged by the SEC, The DAO had other lingering issues. Due to a (now) infamous technical flaw, one or more hackers were able to drain The DAO of a portion of its assets creating confusion as to both the liability of the hacker, as well as the liability of The DAO members to one another. Because The DAO was organized as a for-profit venture, in many jurisdictions (including the US), The DAO likely would have been considered an unincorporated partnership, creating knotty legal questions about liability for the loss of funds.

Next Generation DAOs

Despite these technical and legal challenges, the luster of DAOs has not dulled. Over the past several years, we’ve seen a number of projects seeking to organize as decentralized autonomous organizations and increased tooling (from Aragon and others) to make organizing and managing these entities easier and simpler. Developers are experimenting with new governance models and new bottom-up approaches to organizing social and economic activity.

Moloch is one such emerging blockchain-based governance model that has narrowly focused its technical and game theory design choices to coordinate charity grants for Ethereum projects, pushing its core governance to a vote-weighted multi-signature smart contract with a “ragequit” mechanism that allows its membership to opt-out and receive a proportion of the custodied funds equal to their voting weight at any time.

In this way, participating Moloch DAO members are able to retain control over their contributions and resist attacks with additional protections, such as anti-dilution scripts that ensure that the combination of a proposal and related Moloch ragequitting will not cause greater than three times the dilution to any member.

Introducing the LAO

At OpenLaw, we’ve been actively studying the implications of these tools and their ability to create borderless and more scalable online cooperation. These initial use cases highlight that DAOs thus far have been deployed to coordinate grants in digital assets to fund public goods like open-source software and harden post-ICO treasury management, leveraging Ethereum smart contracts to custody and enforce governance outcomes over pooled ether and ERC20 digital tokens.

Yet, the current models for DAOs is limited. Under current laws, DAOs that are solely governed by smart contracts are restricted in their ability to pool assets from various members and generate a profit. If DAOs are organized for profit they run into securities laws issues, limiting their application and ability to fund ecosystem development and deploy capital efficiently. Even if DAOs are organized for charitable or social purposes, they run into legal gray areas where members may be considered partners and thus each member individually liable for the activity of the organization.

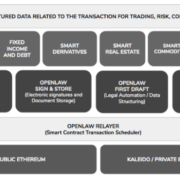

OpenLaw’s tooling helps solve these issues. OpenLaw is the first fully expressive Ricardian contracting system — the bridge between traditional legal regimes and the Ethereum world. OpenLaw can be used to create binding legal agreements and tie them to the execution of one or more smart contracts, including smart contracts that create and manage tokens. Through this approach, any token operating on Ethereum and any smart contract can be imbued with legal effect.

Using OpenLaw, DAOs can be set up as traditional legal entities and can use binding legal agreements to effectuate the transfer of assets or to perform other tasks. We have already demonstrated this possibility through the launch of our vertical OpenLaw DAO. We now are extending this concept with the launch of the LAO. Much like how Coinbase helped bring the trading of traditional assets to millions by attempting to comply with various legal requirements, OpenLaw will help to resurrect the initial vision of The DAO in a manner that comports with U.S. law.

The Structure of The LAO for Members

The LAO will provide a legal structure to enable members to not just give grants, but to invest in blockchain-based projects in exchange for tokenized stock or utility tokens. Projects or Ethereum-based projects will be able to receive funding for their projects in days once submitted to the LAO.

Using the tooling provided by OpenLaw, the LAO will be set up as a limited liability entity, organized in Delaware, using curated smart contracts to handle mechanics related to voting, funding, and allocation of collected funds. This entity will presumably limit the liability of LAO members and help clarify their relationship to avoid knotty questions related as to whether partnership law applies. This structure will also provide members of the LAO with tax flow — through treatment by the Internal Revenue Service, such that tax is not paid by both the entity and a person holding a beneficial interest in the LAO.

Members will be able to purchase interests in the LAO and the proceeds from the purchase will be pooled and allocated by members to startups and other projects in need of financing, using a voting mechanism and tools similar to Moloch DAO.

In order to comply with United States law, membership interests of the LAO will be limited and only available to parties that meet the definition of an accredited investor — although there are arguments that LAO membership interests may not be securities. And, the LAO will be anchored by 10 founding members (which will be announced shortly). Other interested parties will be able to purchase interests in the LAO (potentially through a public sale).

Through OpenLaw’s tools, the creation and set up of The LAO will be streamlined. All of the relevant legal documents from the entity formation documents to member subscription agreements will be generated via the OpenLaw protocol — taking complex corporate financial processes and streamlining their operation — while also providing members with the backing of the U.S. legal system. We also will be exploring on-chain verification of accredited status for the LAO using third-party oracle services (such as ChainLink) to streamline the onboarding process.

Much like the original Moloch design, members of the LAO will be able to ragequit and immediately retrieve back their fair share of unallocated funds based on their economic contribution (regardless of voting weight). With this safety mechanism in place, LAO members will always have the option to opt-out of the LAO should they disagree with aspects of the LAO membership, investment portfolio or need to rapidly receive back their assets. Extending emerging Moloch designs further, LAO members can also continuously claim their fair share of profits provided by tokens received from projects that receive investment from the LAO, further incentivizing collective LAO diligence, voting participation, and membership stability.

The Application Process of Members

The LAO will allocate to potential projects funding in Ether (or potentially DAI ◈). Funding will be provided once a member nominates a project for funding and a majority of the members (based on their voting weight) approve the allocation of funds.

The funding will be provided on a take it or leave it basis. The LAO will receive a certain portion of the projects tokenized stock or other ERC-20 token in exchange for a fixed amount of funding from the LAO.

To accept funding, projects will submit an application and be required to create a Delaware legal entity and OpenLaw will provide a set of standardized documents to streamline the process. If the project is later stage, OpenLaw will work with the project to ensure that the LAO can provide funding, given the project or entity’s then-current legal structure.

Through this approach, a project can conceivably submit a request for funding and receive funding from the LAO in days. Below is a quick preview of how fast funding can be received.

OpenLaw’s Role

OpenLaw’s role in the creation and maintenance of the LAO will be that of an administrator. OpenLaw will help on an ongoing basis with any ongoing legal requirements and improve any tooling that may be necessary to maintain or enhance the LAO. However, OpenLaw will exercise no control over the LAO unless directed by the members.

For these services, OpenLaw will receive a fee for its role in creating and maintaining the software necessary to create LAOs. The fee will be used to pay for ongoing software development and other costs necessary to set up and maintain the OpenLaw protocol. The LAO will have no general partner and OpenLaw will not earn any carry or other forms of the LAO’s potential profits — this will go directly back to the members’ wallets.

The Future of LAOs

The DAO painted a vision for the future of organizations and financing. It relied on the wisdom of the crowd to fund novel projects and automated key aspects of the governance process using smart contracts.

There is a strong argument that if The DAO didn’t collapse for technical or legal reasons the boom of the ICO market would have been tempered if not entirely unnecessary.

With the LAO, experimentation with automated governance and the allocation of funds for profit can begin again, spurring innovation in areas like real time royalty and dividend payments, markets for delegates voting rights, and other synthetic assets involving tokenized stock or utility tokens.

The LAO and similar structures could lead to increased development of secondary trading for LAO interests either through private markets or potentially even on public exchanges, potentially leading to a future of publicly traded venture capital funds.

Over the long run, LAOs can be set up for other protocols and blockchain-based ecosystems helping to ensure that protocol developers and other early supporters of protocol can continue to fuel network development without needing to be a limited partner of a large venture capital fund.

Learn More

To learn more about The LAO, sign-up and continue the conversation on our Telegram and follow us on our Twitter. We are looking for input and feedback to make sure that we can take the next step in the evolution of DAOs.

Hinterlasse einen Kommentar

An der Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlasse uns deinen Kommentar!