Special thanks to Robert Sams for the development of Seignorage Shares and insights regarding how to correctly value volatile coins in multi-currency systems

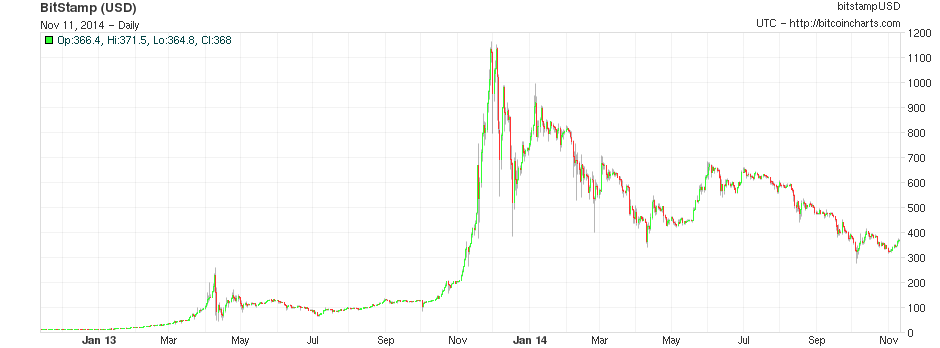

One of the main problems with Bitcoin for ordinary users is that, while the network may be a great way of sending payments, with lower transaction costs, much more expansive global reach, and a very high level of censorship resistance, Bitcoin the currency is a very volatile means of storing value. Although the currency had by and large grown by leaps and bounds over the past six years, especially in financial markets past performance is no guarantee (and by efficient market hypothesis not even an indicator) of future results of expected value, and the currency also has an established reputation for extreme volatility; over the past eleven months, Bitcoin holders have lost about 67% of their wealth and quite often the price moves up or down by as much as 25% in a single week. Seeing this concern, there is a growing interest in a simple question: can we get the best of both worlds? Can we have the full decentralization that a cryptographic payment network offers, but at the same time have a higher level of price stability, without such extreme upward and downward swings?

Last week, a team of Japanese researchers made a proposal for an “improved Bitcoin“, which was an attempt to do just that: whereas Bitcoin has a fixed supply, and a volatile price, the researchers’ Improved Bitcoin would vary its supply in an attempt to mitigate the shocks in price. However, the problem of making a price-stable cryptocurrency, as the researchers realized, is much different from that of simply setting up an inflation target for a central bank. The underlying question is more difficult: how do we target a fixed price in a way that is both decentralized and robust against attack?

To resolve the issue properly, it is best to break it down into two mostly separate sub-problems:

- How do we measure a currency’s price in a decentralized way?

- Given a desired supply adjustment to target the price, to whom do we issue and how do we absorb currency units?

Decentralized Measurement

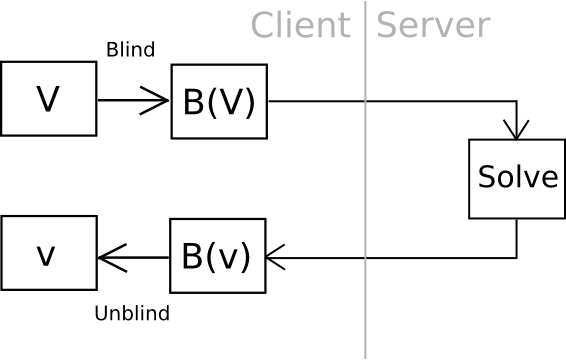

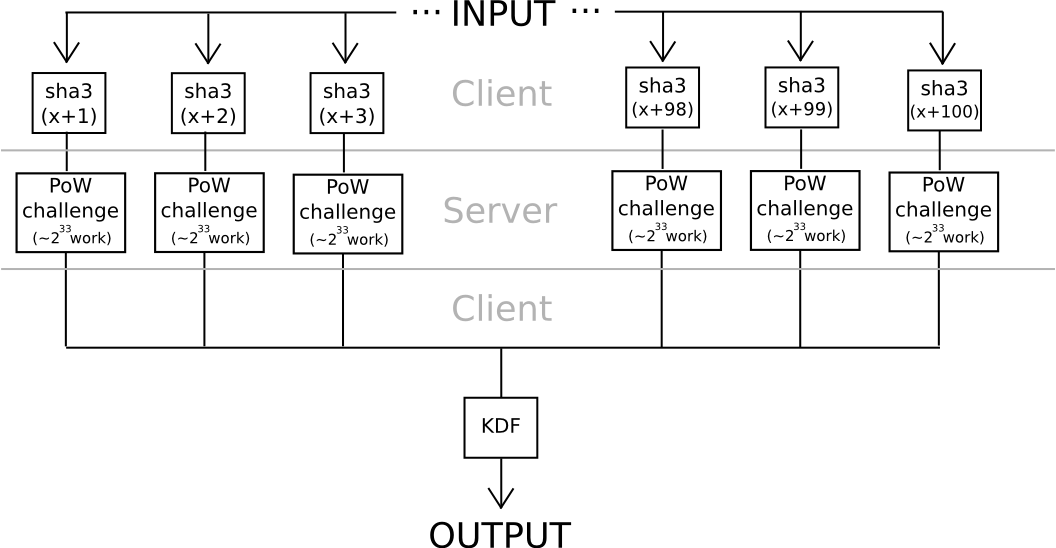

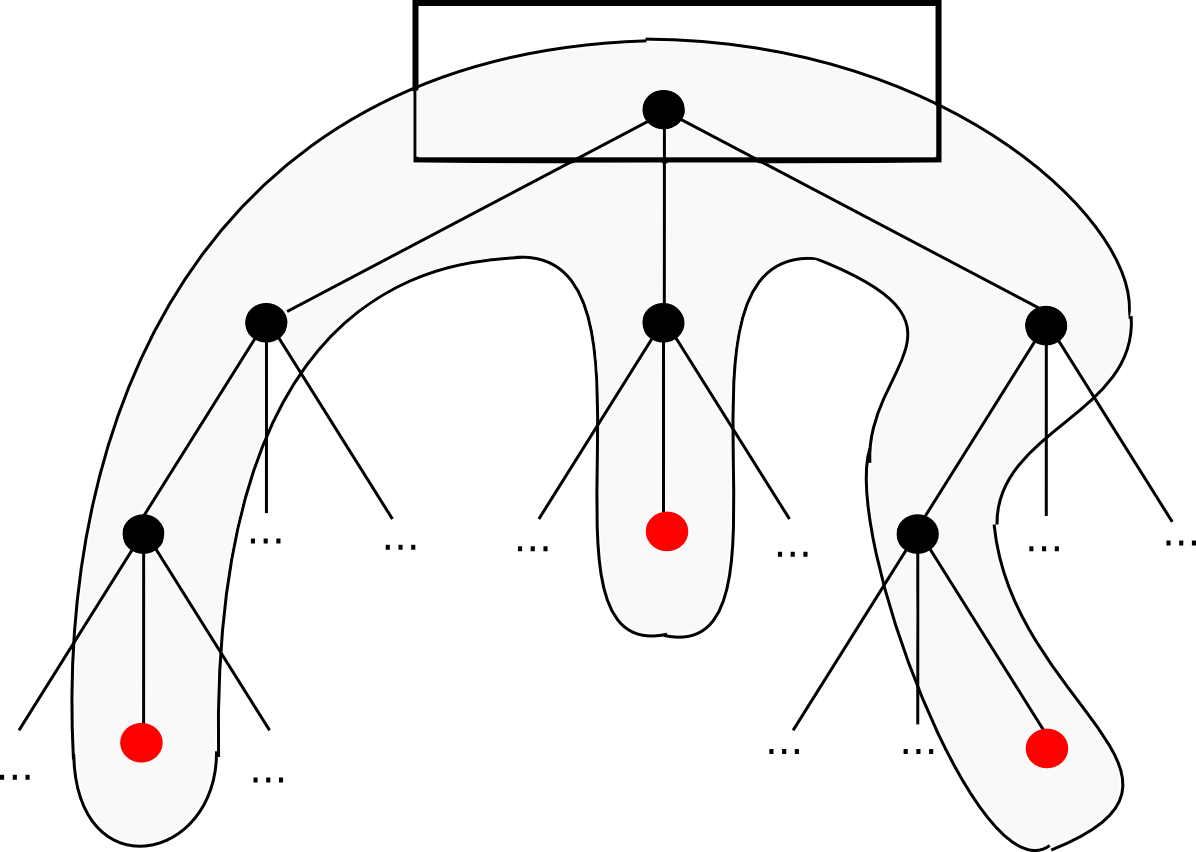

For the decentralized measurement problem, there are two known major classes of solutions: exogenous solutions, mechanisms which try to measure the price with respect to some precise index from the outside, and endogenous solutions, mechanisms which try to use internal variables of the network to measure price. As far as exogenous solutions go, so far the only reliable known class of mechanisms for (possibly) cryptoeconomically securely determining the value of an exogenous variable are the different variants of Schellingcoin – essentially, have everyone vote on what the result is (using some set chosen randomly based on mining power or stake in some currency to prevent sybil attacks), and reward everyone that provides a result that is close to the majority consensus. If you assume that everyone else will provide accurate information, then it is in your interest to provide accurate information in order to be closer to the consensus – a self-reinforcing mechanism much like cryptocurrency consensus itself.

There are three major factors that can influence the extent of this vulnerability:

- Is it likely that the participants in a schellingcoin actually have a common incentive to bias the result in some direction?

- Do the participants have some common stake in the system that would be devalued if the system were to be dishonest?

- Is it possible to “credibly commit” to a particular answer (ie. commit to providing the answer in a way that obviously can’t be changed)?

(1) is rather problematic for single-currency systems, as if the set of participants is chosen by their stake in the currency then they have a strong incentive to pretend the currency price is lower so that the compensation mechanism will push it up, and if the set of participants is chosen by mining power then they have a strong incentive to pretend the currency’s price is too high so as to increase the issuance. Now, if there are two kinds of mining, one of which is used to select Schellingcoin participants and the other to receive a variable reward, then this objection no longer applies, and multi-currency systems can also get around the problem. (2) is true if the participant selection is based on either stake (ideally, long-term bonded stake) or ASIC mining, but false for CPU mining. However, we should not simply count on this incentive to outweigh (1).

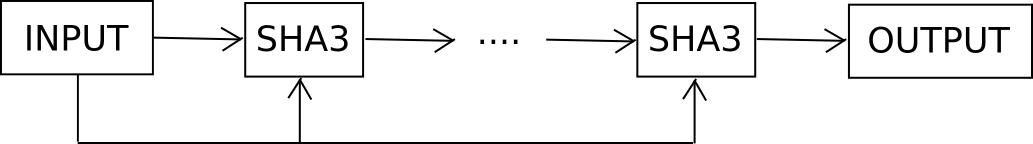

(3) is perhaps the hardest; it depends on the precise technical implementation of the Schellingcoin. A simple implementation involving simply submitting the values to the blockchain is problematic because simply submitting one’s value early is a credible commitment. The original SchellingCoin used a mechanism of having everyone submit a hash of the value in the first round, and the actual value in the second round, sort of a cryptographic equivalent to requiring everyone to put down a card face down first, and then flip it at the same time; however, this too allows credible commitment by revealing (even if not submitting) one’s value early, as the value can be checked against the hash.

A third option is requiring all of the participants to submit their values directly, but only during a specific block; if a participant does release a submission early they can always “double-spend” it. The 12-second block time would mean that there is almost no time for coordination. The creator of the block can be strongly incentivized (or even, if the Schellingcoin is an independent blockchain, required) to include all participations, to discourage or prevent the block maker from picking and choosing answers. A fourth class of options involves some secret sharing or secure multiparty computation mechanism, using a collection of nodes, themselves selected by stake (perhaps even the participants themselves), as a sort of decentralized substitute for a centralized server solution, with all the privacy that such an approach entails.

Finally, a fifth strategy is to do the schellingcoin “blockchain-style”: every period, some random stakeholder is selected, and told to provide their vote as a [id, value] pair, where value is the actual valid and id is an identifier of the previous vote that looks correct. The incentive to vote correctly is that only tests that remain in the main chain after some number of blocks are rewarded, and future voters will note attach their vote to a vote that is incorrect fearing that if they do voters after them will reject their vote.

Schellingcoin is an untested experiment, and so there is legitimate reason to be skeptical that it will work; however, if we want anything close to a perfect price measurement scheme it’s currently the only mechanism that we have. If Schellingcoin proves unworkable, then we will have to make do with the other kinds of strategies: the endogenous ones.

Endogenous Solutions

To measure the price of a currency endogenously, what we essentially need is to find some service inside the network that is known to have a roughly stable real-value price, and measure the price of that service inside the network as measured in the network’s own token. Examples of such services include:

- Computation (measured via mining difficulty)

- Transaction fees

- Data storage

- Bandwidth provision

A slightly different, but related, strategy, is to measure some statistic that correllates indirectly with price, usually a metric of the level of usage; one example of this is transaction volume.

The problem with all of these services is, however, that none of them are very robust against rapid changes due to technological innovation. Moore’s Law has so far guaranteed that most forms of computational services become cheaper at a rate of 2x every two years, and it could easily speed up to 2x every 18 months or 2x every five years. Hence, trying to peg a currency to any of those variables will likely lead to a system which is hyperinflationary, and so we need some more advanced strategies for using these variables to determine a more stable metric of the price.

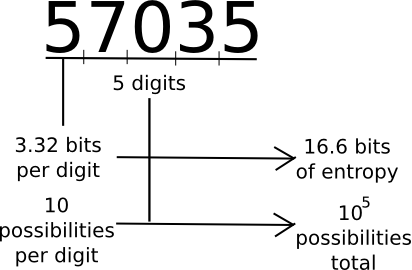

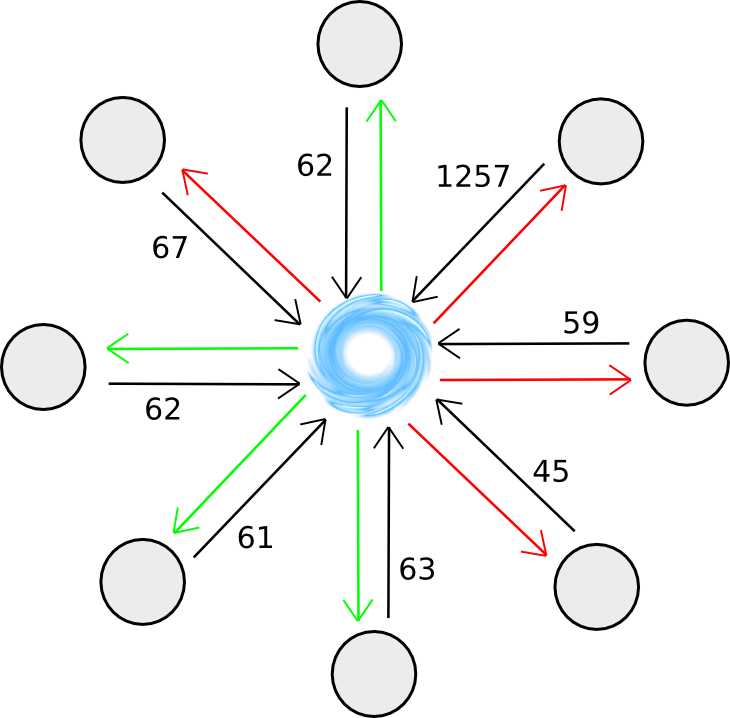

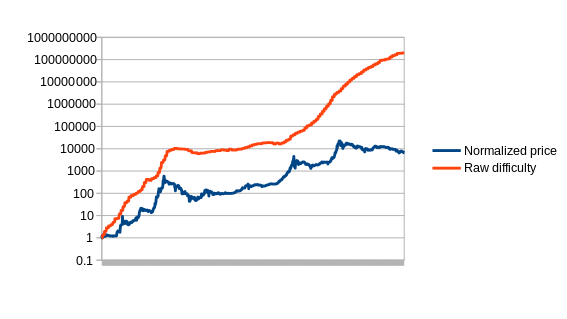

First, let us set up the problem. Formally, we define an estimator to be a function which receives a data feed of some input variable (eg. mining difficulty, transaction cost in currency units, etc) D[1], D[2], D[3]…, and needs to output a stream of estimates of the currency’s price, P[1], P[2], P[3]… The estimator obviously cannot look into the future; P[i] can be dependent on D[1], D[2] … D[i], but not D[i+1]. Now, to start off, let us graph the simplest possible estimator on Bitcoin, which we’ll call the naive estimator: difficulty equals price.

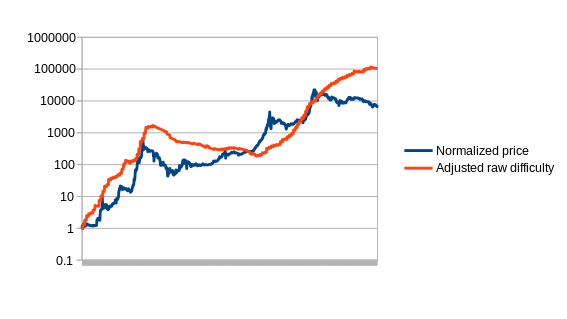

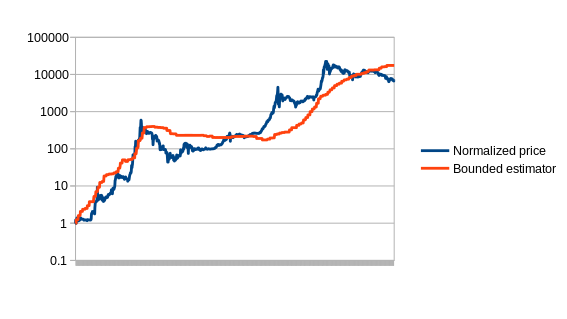

The way that we will select the parameter for our version is by using a variant of simulated annealing to find the optimal values, using the first 780 days of the Bitcoin price as “training data”. The estimators are then left to perform as they would for the remaining 780 days, to see how they would react to conditions that were unknown when the parameters were optimized (this technique, knows as “cross-validation”, is standard in machine learning and optimization theory). The optimal value for the compensated estimator is a drop of 0.48% per day, leading to this chart:

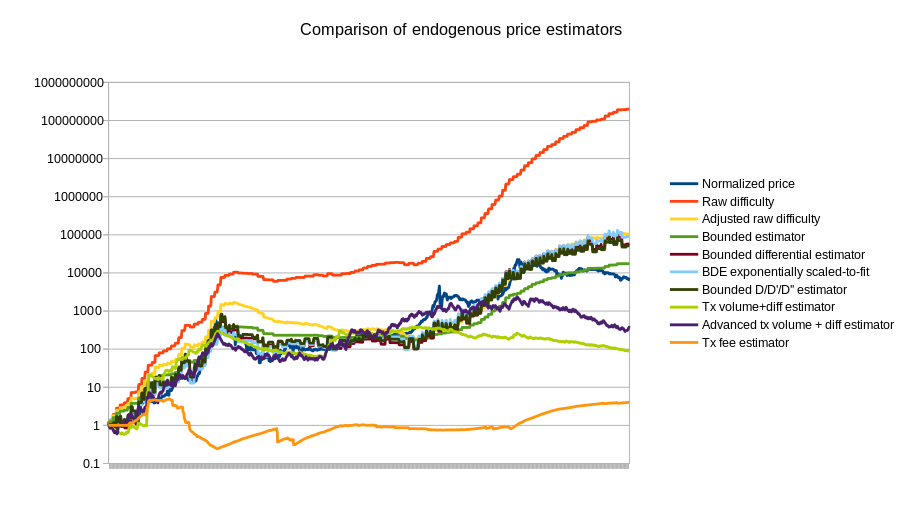

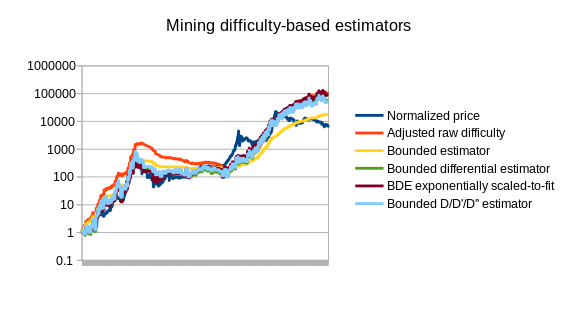

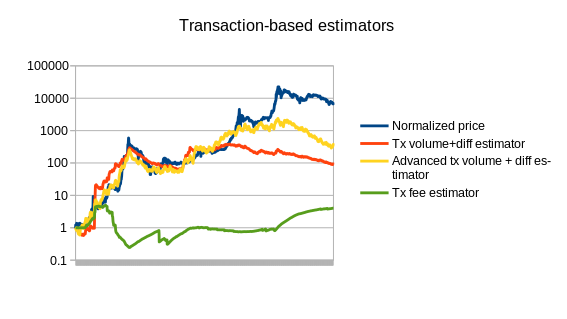

Note that the chart also includes three estimators that use statistics other than Bitcoin mining: a simple and an advanced estimator using transaction volume, and an estimator using the average transaction fee. We can also split up the mining-based estimators from the other estimators:

|

|

See https://github.com/ethereum/economic-modeling/tree/master/stability for the source code that produced these results.

Of course, this is only the beginning of endogenous price estimator theory; a more thorough analysis involving dozens of cryptocurrencies will likely go much further. The best estimators may well end up using a combination of different measures; seeing how the difficulty-based estimators overshot the price in 2014 and the transaction-based estimators undershot the price, the two combined could end up being substantially more accurate. The problem is also going to get easier over time as we see the Bitcoin mining economy stabilize toward something closer to an equilibrium where technology improves only as fast as the general Moore’s law rule of 2x every 2 years.

The other issue that all of these estimators have to contend with is exploitability: if transaction volume is used to determine the currency’s price, then an attacker can manipulate the price very easily by simply sending very many transactions. The average transaction fees paid in Bitcoin are about $ 5000 per day; at that price in a stabilized currency the attacker would be able to halve the price. Mining difficulty, however, is much more difficult to exploit simply because the market is so large. If a platform does not want to accept the inefficiencies of wasteful proof of work, an alternative is to build in a market for other resources, such as storage, instead; Filecoin and Permacoin are two efforts that attempt to use a decentralized file storage market as a consensus mechanism, and the same market could easily be dual-purposed to serve as an estimator.

The Issuance Problem

Now, even if we have a reasonably good, or even perfect, estimator for the currency’s price, we still have the second problem: how do we issue or absorb currency units? The simplest approach is to simply issue them as a mining reward, as proposed by the Japanese researchers. However, this has two problems:

- Such a mechanism can only issue new currency units when the price is too high; it cannot absorb currency units when the price is too low.

- If we are using mining difficulty in an endogenous estimator, then the estimator needs to take into account the fact that some of the increases in mining difficulty will be a result of an increased issuance rate triggered by the estimator itself.

If not handled very carefully, the second problem has the potential to create some rather dangerous feedback loops in either direction; however, if we use a different market as an estimator and as an issuance model then this will not be a problem. The first problem seems serious; in fact, one can interpret it as saying that any currency using this model will always be strictly worse than Bitcoin, because Bitcoin will eventually have an issuance rate of zero and a currency using this mechanism will have an issuance rate always above zero. Hence, the currency will always be more inflationary, and thus less attractive to hold. However, this argument is not quite true; the reason is that when a user purchases units of the stabilized currency then they have more confidence that at the time of purchase the units are not already overvalued and therefore will soon decline. Alternatively, one can note that extremely large swings in price are justified by changing estimations of the probability the currency will become thousands of times more expensive; clipping off this possibility will reduce the upward and downward extent of these swings. For users who care about stability, this risk reduction may well outweigh the increased general long-term supply inflation.

BitAssets

A second approach is the (original implementation of the) “bitassets” strategy used by Bitshares. This approach can be described as follows:

- There exist two currencies, “vol-coins” and “stable-coins”.

- Stable-coins are understood to have a value of $ 1.

- Vol-coins are an actual currency; users can have a zero or positive balance of them. Stable-coins exist only in the form of contracts-for-difference (ie. every negative stable-coin is really a debt to someone else, collateralized by at least 2x the value in vol-coins, and every positive stable-coin is the ownership of that debt).

- If the value of someone’s stable-coin debt exceeds 90% of the value of their vol-coin collateral, the debt is cancelled and the entire vol-coin collateral is transferred to the counterparty (“margin call”)

- Users are free to trade vol-coins and stable-coins with each other.

And that’s it. The key piece that makes the mechanism (supposedly) work is the concept of a “market peg”: because everyone understands that stable-coins are supposed to be worth $ 1, if the value of a stable-coin drops below $ 1, then everyone will realize that it will eventually go back to $ 1, and so people will buy it, so it actually will go back to $ 1 – a self-fulfilling prophecy argument. And for a similar reason, if the price goes above $ 1, it will go back down. Because stable-coins are a zero-total-supply currency (ie. each positive unit is matched by a corresponding negative unit), the mechanism is not intrinsically unworkable; a price of $ 1 could be stable with ten users or ten billion users (remember, fridges are users too!).

However, the mechanism has some rather serious fragility properties. Sure, if the price of a stable-coin goes to $ 0.95, and it’s a small drop that can easily be corrected, then the mechanism will come into play, and the price will quickly go back to $ 1. However, if the price suddenly drops to $ 0.90, or lower, then users may interpret the drop as a sign that the peg is actually breaking, and will start scrambling to get out while they can – thus making the price fall even further. At the end, the stable-coin could easily end up being worth nothing at all. In the real world, markets do often show positive feedback loops, and it is quite likely that the only reason the system has not fallen apart already is because everyone knows that there exists a large centralized organization (BitShares Inc) which is willing to act as a buyer of last resort to maintain the “market” peg if necessary.

Note that BitShares has now moved to a somewhat different model involving price feeds provided by the delegates (participants in the consensus algorithm) of the system; hence the fragility risks are likely substantially lower now.

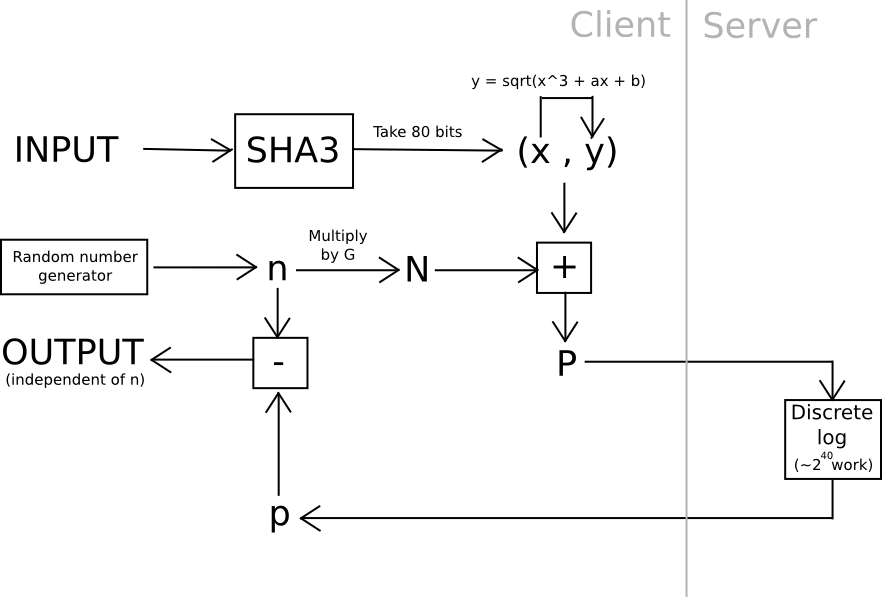

SchellingDollar

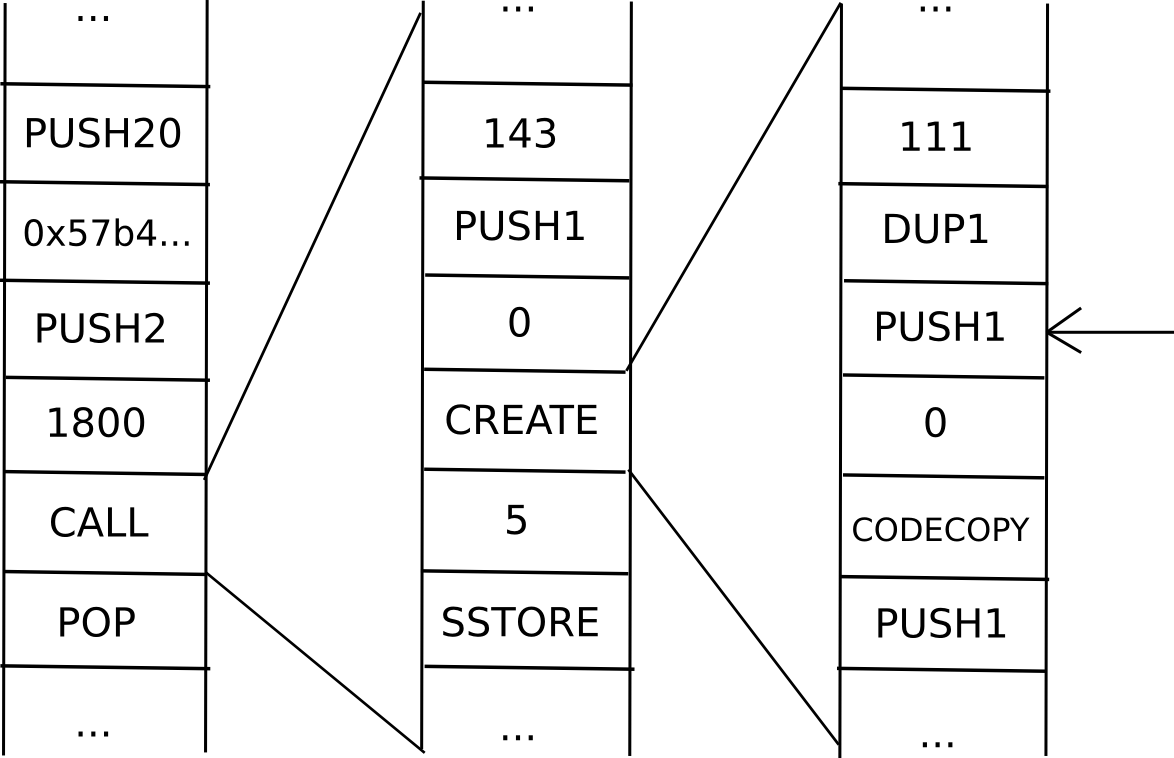

An approach vaguely similar to BitAssets that arguably works much better is the SchellingDollar (called that way because it was originally intended to work with the SchellingCoin price detection mechanism, but it can also be used with endogenous estimators), defined as follows:

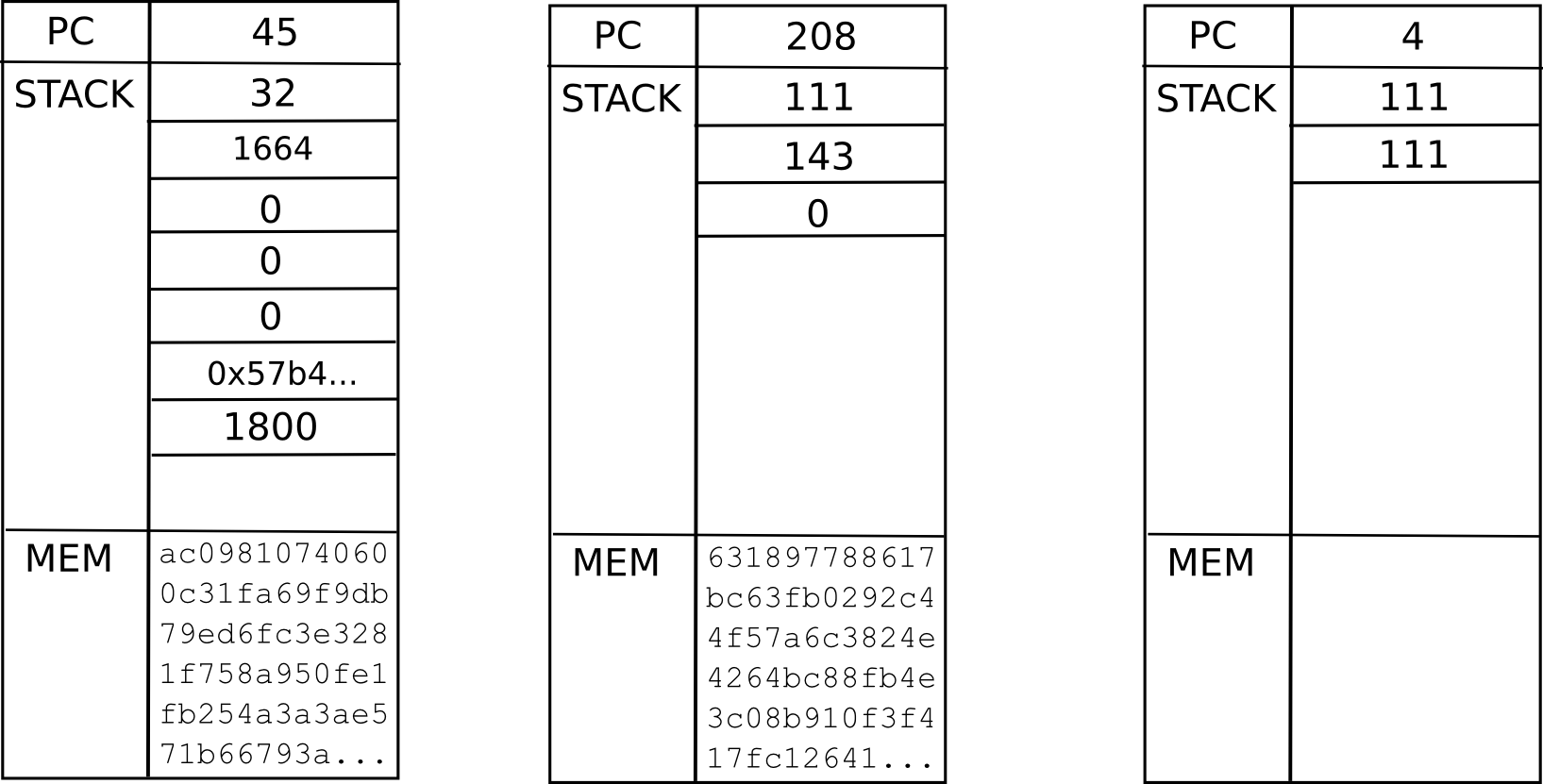

- There exist two currencies, “vol-coins” and “stable-coins”. Vol-coins are initially distributed somehow (eg. pre-sale), but initially no stable-coins exist.

- Users may have only a zero or positive balance of vol-coins. Users may have a negative balance of stable-coins, but can only acquire or increase their negative balance of stable-coins if they have a quantity of vol-coins equal in value to twice their new stable-coin balance (eg. if a stable-coin is $ 1 and a vol-coin is $ 5, then if a user has 10 vol-coins ($ 50) they can at most reduce their stable-coin balance to -25)

- If the value of a user’s negative stable-coins exceeds 90% of the value of the user’s vol-coins, then the user’s stable-coin and vol-coin balances are both reduced to zero (“margin call”). This prevents situations where accounts exist with negative-valued balances and the system goes bankrupt as users run away from their debt.

- Users can convert their stable-coins into vol-coins or their vol-coins into stable-coins at a rate of $ 1 worth of vol-coin per stable-coin, perhaps with a 0.1% exchange fee. This mechanism is of course subject to the limits described in (2).

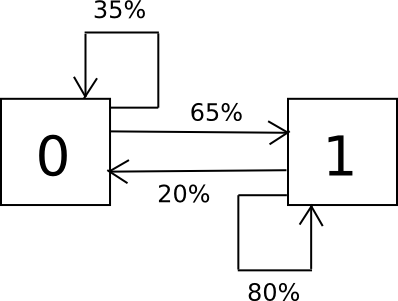

- The system keeps track of the total quantity of stable-coins in circulation. If the quantity exceeds zero, the system imposes a negative interest rate to make positive stable-coin holdings less attractive and negative holdings more attractive. If the quantity is less than zero, the system similarly imposes a positive interest rate. Interest rates can be adjusted via something like a PID controller, or even a simple “increase or decrease by 0.2% every day based on whether the quantity is positive or negative” rule.

Here, we do not simply assume that the market will keep the price at $ 1; instead, we use a central-bank-style interest rate targeting mechanism to artificially discourage holding stable-coin units if the supply is too high (ie. greater than zero), and encourage holding stable-coin units if the supply is too low (ie. less than zero). Note that there are still fragility risks here. First, if the vol-coin price falls by more than 50% very quickly, then many margin call conditions will be triggered, drastically shifting the stable-coin supply to the positive side, and thus forcing a high negative interest rate on stable-coins. Second, if the vol-coin market is too thin, then it will be easily manipulable, allowing attackers to trigger margin call cascades.

Another concern is, why would vol-coins be valuable? Scarcity alone will not provide much value, since vol-coins are inferior to stable-coins for transactional purposes. We can see the answer by modeling the system as a sort of decentralized corporation, where “making profits” is equivalent to absorbing vol-coins and “taking losses” is equivalent to issuing vol-coins. The system’s profit and loss scenarios are as follows:

- Profit: transaction fees from exchanging stable-coins for vol-coins

- Profit: the extra 10% in margin call situations

- Loss: situations where the vol-coin price falls while the total stable-coin supply is positive, or rises while the total stable-coin supply is negative (the first case is more likely to happen, due to margin-call situations)

- Profit: situations where the vol-coin price rises while the total stable-coin supply is positive, or falls while it’s negative

Note that the second profit is in some ways a phantom profit; when users hold vol-coins, they will need to take into account the risk that they will be on the receiving end of this extra 10% seizure, which cancels out the benefit to the system from the profit existing. However, one might argue that because of the Dunning-Kruger effect users might underestimate their susceptibility to eating the loss, and thus the compensation will be less than 100%.

Now, consider a strategy where a user tries to hold on to a constant percentage of all vol-coins. When x% of vol-coins are absorbed, the user sells off x% of their vol-coins and takes a profit, and when new vol-coins equal to x% of the existing supply are released, the user increases their holdings by the same portion, taking a loss. Thus, the user’s net profit is proportional to the total profit of the system.

Seignorage Shares

A fourth model is “seignorage shares”, courtesy of Robert Sams. Seignorage shares is a rather elegant scheme that, in my own simplified take on the scheme, works as follows:

- There exist two currencies, “vol-coins” and “stable-coins” (Sams uses “shares” and “coins”, respectively)

- Anyone can purchase vol-coins for stable-coins or vol-coins for stable-coins from the system at a rate of $ 1 worth of vol-coin per stable-coin, perhaps with a 0.1% exchange fee

Note that in Sams’ version, an auction was used to sell off newly-created stable-coins if the price goes too high, and buy if it goes too low; this mechanism basically has the same effect, except using an always-available fixed price in place of an auction. However, the simplicity comes at the cost of some degree of fragility. To see why, let us make a similar valuation analysis for vol-coins. The profit and loss scenarios are simple:

- Profit: absorbing vol-coins to issue new stable-coins

- Loss: issuing vol-coins to absorb stable-coins

The same valuation strategy applies as in the other case, so we can see that the value of the vol-coins is proportional to the expected total future increase in the supply of stable-coins, adjusted by some discounting factor. Thus, here lies the problem: if the system is understood by all parties to be “winding down” (eg. users are abandoning it for a superior competitor), and thus the total stable-coin supply is expected to go down and never come back up, then the value of the vol-coins drops below zero, so vol-coins hyperinflate, and then stable-coins hyperinflate. In exchange for this fragility risk, however, vol-coins can achieve a much higher valuation, so the scheme is much more attractive to cryptoplatform developers looking to earn revenue via a token sale.

Note that both the SchellingDollar and seignorage shares, if they are on an independent network, also need to take into account transaction fees and consensus costs. Fortunately, with proof of stake, it should be possible to make consensus cheaper than transaction fees, in which case the difference can be added to profits. This potentially allows for a larger market cap for the SchellingDollar’s vol-coin, and allows the market cap of seignorage shares’ vol-coins to remain above zero even in the event of a substantial, albeit not total, permanent decrease in stable-coin volume. Ultimately, however, some degree of fragility is inevitable: at the very least, if interest in a system drops to near-zero, then the system can be double-spent and estimators and Schellingcoins exploited to death. Even sidechains, as a scheme for preserving one currency across multiple networks, are susceptible to this problem. The question is simply (1) how do we minimize the risks, and (2) given that risks exist, how do we present the system to users so that they do not become overly dependent on something that could break?

Conclusions

Are stable-value assets necessary? Given the high level of interest in “blockchain technology” coupled with disinterest in “Bitcoin the currency” that we see among so many in the mainstream world, perhaps the time is ripe for stable-currency or multi-currency systems to take over. There would then be multiple separate classes of cryptoassets: stable assets for trading, speculative assets for investment, and Bitcoin itself may well serve as a unique Schelling point for a universal fallback asset, similar to the current and historical functioning of gold.

If that were to happen, and particularly if the stronger version of price stability based on Schellingcoin strategies could take off, the cryptocurrency landscape may end up in an interesting situation: there may be thousands of cryptocurrencies, of which many would be volatile, but many others would be stable-coins, all adjusting prices nearly in lockstep with each other; hence, the situation could even end up being expressed in interfaces as a single super-currency, but where different blockchains randomly give positive or negative interest rates, much like Ferdinando Ametrano’s “Hayek Money”. The true cryptoeconomy of the future may have not even begun to take shape.

The post The Search for a Stable Cryptocurrency appeared first on ethereum blog.